A Perfect Bedtime Story

I know, I know…I’ve been terribly inconsistent of late, and for that I’m sorry. Although my reason for not writing is simply the fact that I am having fun in the summer sun (and work has been really busy recently - ugh), I know that you have all been sitting around doing nothing, waiting for my next post. Well, wait no more!

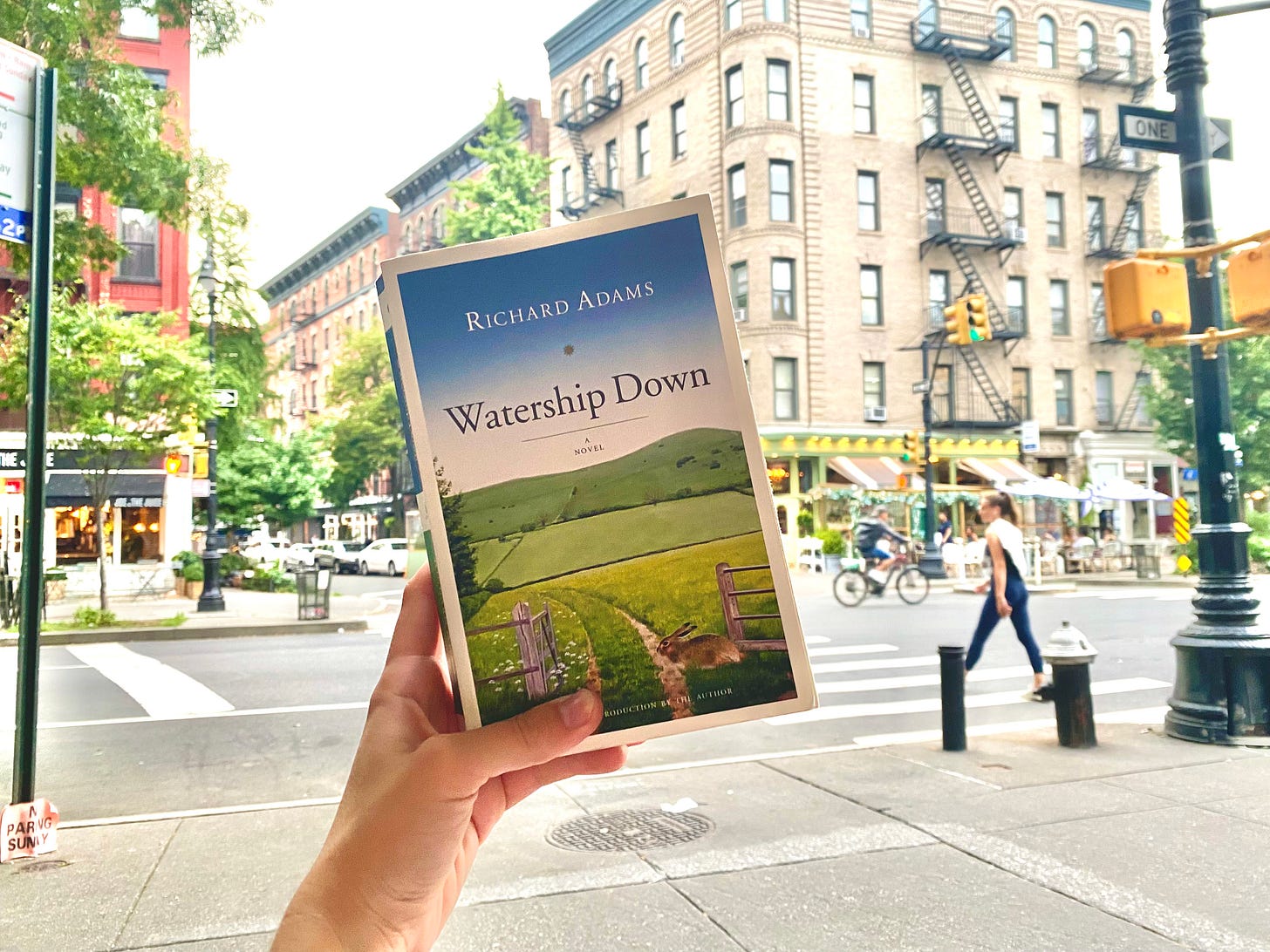

Today I will be telling you about the incredible, wonderful, everything good, nothing bad, story, Watership Down by Richard Adams. As loyal readers know, I like to read before bed, and this one might take the cake for best bedtime story ever. It is a novel, but I will refer to it as a story throughout because that’s what it is: a story. Tale would also be appropriate, and perhaps satisfyingly punny because it’s about rabbits. A rabbit tale. Ha ha. What would also be appropriate, would be allegory or collection of parables, but Adams insists that neither was the intention in his introduction, included in my edition (2005, Scribner). Aside from that interesting tidbit, which I will touch upon later, Adams’s introduction also includes the lovely recounting of how Watership Down came to be.

You see, Richard Adams was not an author, and - though I can’t ask him, I would guess - had no real intention to become one until it happened. He was born in 1920 in Berkshire England, he studied modern history at Oxford, he was called to serve in 1940, although he saw no action against either the Germans or the Japanese. All of this according to Wikipedia, obviously. He left the army in 1946, went back to school, and shortly thereafter entered into the civil service. He was 46 years old when he started writing Watership Down, and 52 years old when it was finally published - due entirely to his own persistence in the face of rejection. It was a novel that he wrote down at the insistence of, and with the help of, his two daughters, for whom he had created the story out of thin air on a long drive. He also credits R. M. Lockley, a naturalist and ornithologist, and the author of The Private Life of the Rabbit, for helping to “make the rabbits as convincing as possible” (Adams xiii). I mention this because whatever R. M. Lockley told him did the trick. I will never look at rabbits the same again (in a good way).

On plot, I really don’t want to give too much away because it is such a wonderful adventure. It begins with two rabbits, Hazel and Fiver who live in Sandleford Warren. Fiver, modeled off of tragic Cassandra, with the gift of prophecy and the curse of never being believed, has a premonition of evil to come. Hazel, with the wherewithal to actually take action, devises a plan to leave the warren. Thus begins the story. When their chief rabbit won’t heed Fiver’s warning, they make a break for it, taking with them a small group of rabbits. Hazel leads the group bravely but quietly, with Fiver as his advisor (who he eventually learns to always try and believe), and they set off in search of a mysterious promised land - high up where everything can be seen for miles around - that Fiver has seen in his visions.

The cast of characters is top notch, including (but not limited to) a stalwart and honorable fighter (Bigwig), a clever, strategist type (Blackberry), and a storyteller (Dandelion). There is also a fantastic, and numerous, supporting cast, including the pure evil antagonist of the story (General Woudwort), a sweet little mouse who the rabbits befriend, and the does, or female rabbits, who enter the scene rather on the later side but who make such a wonderful addition. One of the best though is Kehaar, the injured seagull who is offered protection by the rabbits in the hopes that the favor will be returned one day (spoiler: it is). There is also a wonderful vein of rabbit folklore that runs through the tale with its own cast of characters. Adams went beyond creating a community of rabbits, he also created a mythology for them, which grounds the entire story. I should also mention that he created a language, Lapine, which, though rudimentary, makes it all feel so real.

And on the note of language, one thing that really stood out to me throughout was how well-written the story was. Not just well-written for a children’s book, which it is, but well-written for anything. I suppose thinking about it now, it’s a combination of the subject matter - not softened in the slightest - and the writing style - not dumbed down at all - that really stands out. But it’s such a precarious balance that I think must be difficult to strike - I felt like a child reading it, but it was genuinely thought provoking. I’ve never read anything that has made me feel both of those things at once. Maybe I’m just not reading enough children’s chapter books, but I have a feeling it’s not that. I don’t think they make ‘em like this anymore. What it really makes me want to do is find some more like it because they must exist. I’m thinking Chronicles of Narnia might satisfy my craving, but if you have any recs, drop a line.

To prove my point on how lovely Adams’s style is, I am going to include my favorite, somewhat lengthy, somewhat appended passage from the story here. It runs from page 164-165 in my edition:

“The full moon, well risen in a cloudless eastern sky, covered the high solitude with its light. We are not conscious of daylight as that which displaces darkness. Daylight, even when the sun is clear of clouds, seems to us simply the natural condition of the earth and air…We take daylight for granted. But moonlight is another matter. It is inconstant. The full moon wanes and returns again. Clouds may obscure it to an extent to which they cannot obscure daylight. Water is necessary to us, but a waterfall is not. Where it is to be found it is something extra, a beautiful ornament…”

So good, right??!!!! And there’s absolutely more where that came from!

Quickly before I wrap up, I do want to mention the allegory or not allegory question. Adams says not parable. I say fine, I believe you, but also you’re crazy. Every single obstacle, or blessing (for lack of a better word), that these rabbits encounter could be considered a parable, so ripe with meaning and possible interpretation they are. I was consistently reminded of Pilgrim’s Progress, (single most common example of allegory in the English language) particularly in the earliest parts of our dear rabbits’ journey. Slough of Despond, pit of heather, tomato, tom-ah-to (if you know, you know). I would say though, that the most obvious, and perhaps topical (at least, to me), lessons to be learned centered upon the trade offs that take place when a community (or civilization) chooses safety over freedom. Again, no spoilers - these themes came up over and over again, but certainly most starkly in relation to the rival warren Efrafra: “‘You can’t call your life your own: and in return you have safety - if it’s worth having at the price you pay’” (Adams 233). Truly fascinating and worth the read just for an opportunity to think it over.

Overall, this book made me feel like a child again. I must share that I wept literal tears of joy when I finished it at 11:30pm on a Tuesday night in June. I found out the next morning that at 10:52pm, the moon went into Cancer, which made it an emotional and sentimental time. However, though the actual tears that I cried may have been in part owed to the new moon in Cancer, the underlying feeling was not. I felt it the whole time I was reading - and it was overwhelmingly pleasant and nostalgic. My own father is a wonderful storyteller, who filled my childhood with wonderful tales of pirates and knights in shining armor. The ones that were always my favorites however, were the Heathfield stories, named after the farm on which he grew up, and totally foreign to me, Manhattan child that I was. Much like Watership Down, they were anthropomorphic and full of adventure. To my dad: write them down!

This one is owed to my dear stepmom, Andrea. Thank you for the book, which made me feel like a little kid again every night, just in time for bedtime.