Ada Limón & Joan <3

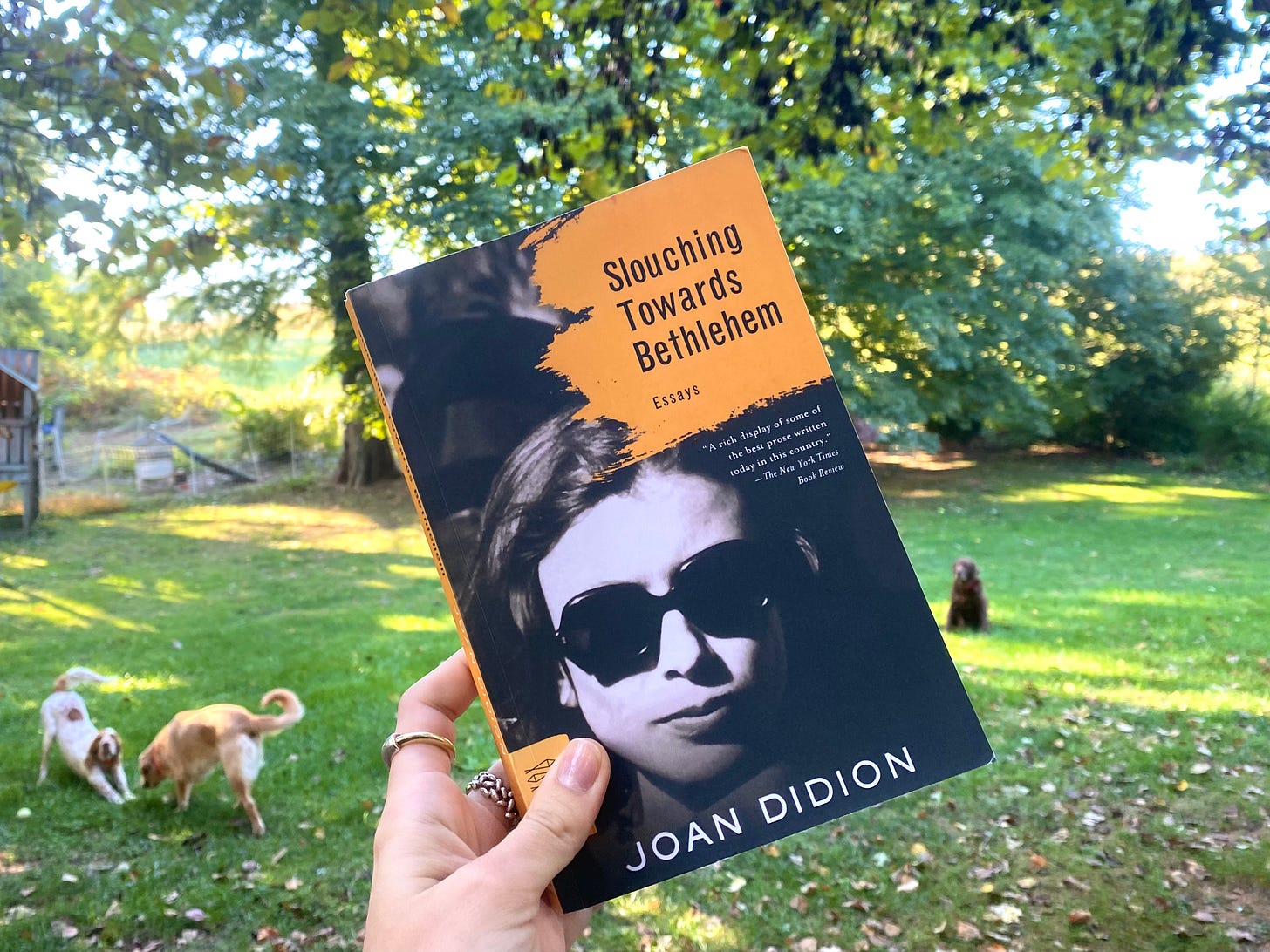

Bright Dead Things by Ada Limón & Slouching Towards Bethlehem by Joan Didion

Happy Friday, dear reader! As promised, I’m back with new material. Whether it’s good material or whether, in the course of a couple weeks, I’ve totally forgotten how to write, I’ll leave up to you. Last month, in addition to a hefty novel that I’m actually still smack dab in the middle of, I read a collection of poetry and a collection of essays. Neither is necessarily a hidden gem, but that’s for good reason. They are excellent books, and I recommend them wholeheartedly. Enjoy!

Bright Dead Things by Ada Limón

When reason-for-staying-on-Instagram @poetryisnotaluxury posted a poem by Ada Limón in early September, I remembered that I had a collection by her sitting on my shelf. It was a good poem, called “The Endlessness,” and feeling the way I did reading it, I decided to take its appearance on my little screen as a sign. Nothing quite like turning any old thing into a sign from the universe.

I picked up Bright Dead Things, and I read it slowly over the course of about a month, which is generally not how I read poetry. I did read through it in order, as I always do. I think this is important in a collection of poetry in the same it is when you sit down to listen to an album. The poet has printed the poems out and laid them down on the floor and moved them around like tiles until it all lined up and made sense—or some version of that at least.

Aside from that though, my approach here was different because I did not read through the book—it’s four parts—in the span of a couple days. I like to read poetry quickly like that because it means central themes and through-lines remain fresh in the mind for the whole reading experience. It creates a cohesion. Instead, with Ada Limón, I lingered, and flagged in my reading, which has left me with more general impressions and feelings.

Don’t get it twisted, that’s not a bad thing. There is one way of reading poetry, like you’re in your high school English class, thinking about motifs and literary devices and analyzing each word and comma. If you’re up for it, you usually come out on the other side feeling like something was revealed to you—maybe even like you had an active part in uncovering it, buried treasure. However, that is not the only way to read poetry! I hesitate to use the words right and wrong, but it might even be the wrong way to read poetry. And unfortunately, I think the fact that many people learn to read poetry like that in high school (or earlier) is the very thing that stops them from continuing to read poetry. For shame!

All you have to do to read and enjoy poetry is pay attention to the way you feel. If you meander through the lines and you don’t understand, or it feels a bit bland, that poem isn’t for you right now. Onward! Take the pressure off. Poetry is about how you feel, and sometimes it’s okay to just say, “I like this poem because it felt good to read it.” It’s even okay to say, “I like it because I like it,” or even just “this poem is good,” with no further explanation of why you think that! We are allowed!! There’s no English teacher docking us for not identifying and defining at least 5 literary devices employed by the poet in XYZ poem.

This is a pep talk to myself, mentally still trying to make sure I get straight A’s on the English papers that I assign myself every week.

Here’s what I remember from Bright Dead Things. Ada Limón writes yearningly, almost mournfully, about place. Whether it’s Brooklyn, or Tennessee or California. It brings to mind the Welsh term that I learned from Sally Mann—hiraeth, or the pain of loving a place.

Ada Limón also speaks my language when she draws attention to the uncommon in the ordinary, the baffling in the every day. She says “I still want to point out the heron like I was taught, / still want to slow the car down to see the thing / that makes it all better, the invisible gift, what / we see when we stare long enough into nothing.” She marvels at the simple act of ordering another margarita when thoughts of death sit down at the table with her in a Mexican restaurant. And she faces the sorrow of death armed with these ordinary every day things. She says life is still joyful because of, not in spite of, no matter how confusing that might be.

She speaks to the natural world, and to the natural beasts that inhabit it. She is one of those beasts, and acknowledges that, saying, “maybe it’s fitting that I’d be the low ugly / alive thing doing my living all over the place.” She has conversations, both real and imaginary with herself, her friends, her lovers, and her ex lovers. Almost every time she punches you in the gut, or licks your ear with her last lines. Always killer closing lines.

That is what I remember about Ada Limón, and for those half-formed reasons I like her and I think her poetry is good. But the real thing I remember about Ada Limón, the thing I keep coming back to and can’t seem to forget is one poem. It is called “The Noisiness of Sleep,” and I don’t know if I’m allowed to, but I’m including a picture of it below. I have to include the picture because I have nothing else to say other than that when I read it, I knew I was reading poetry the right way.

Slouching Towards Bethlehem by Joan Didion

The other book I read last month is also a collection, but this time of essays. Slouching Towards Bethlehem was the first collection of essays or work of nonfiction published by Joan Didion in 1968. My sister bought this book for me after months of telling me to read it—to read anything by Ms. Didion. I figured I would give her the satisfaction.

And it turns out—I gave myself the satisfaction as well. Historically, collections of essays have not been my favorite. I have admittedly little experience, but what I do have hasn’t been inspiring. I often feel like I’m trudging through. Either I get whiplash from jumping from one topic to another or I feel like I’m reading the same essay over and over again with only surface level variations.

It may have something to do with the fact that I want to finish a book when I start it, generally only reading one at a time, and going through each one from start to finish, no skipping or skimming or taking breaks. Maybe collections of essays don’t always lend themselves to that kind of reading?

That’s silly though. Similar to my earlier point about poetry collections, If someone (author, editor, publisher) has decided to put a series of essays together in a particular order, organized into particular sections, there is an argument to be made for reading them from start to finish with -some degree of focus.

All of this is my longwinded way of getting to the point, which is that my experience with Slouching Towards Bethlehem was not a trudge. Nowhere near. In fact, by the time I had made it to the titular essay about a third of the way in, I could not bear to put the thing down. Its just something in the way she writes—not explainable. She has a voice that captures.

It was that voice primarily that created a sense of cohesion within the collection. Sure, there are other themes that run through—the entire first section, “Life Styles in the Golden Land,” is about California. Several other pieces in the second and third section are too. Joan Didion and California, California and Joan Didion—even as someone who had never read her writing, I knew that much. She even writes about New York like a Californian.

What other threads can be traced? The foolishness, foolhardiness of civilized man, his particular tendencies both concerning and bemusing. A woman murders her husband and another one weeps tears of joy after getting married in Las Vegas—it was just as she’d “hoped and dreamed it would be.” Then there’s the three people who live on Alcatraz and the titans of industry building monuments to their wealth on an unforgiving, formerly unbeautiful pile of rock—one Newport, Rhode Island, my favorite place on earth, that Joan calls “The Seacoast of Despair,” There’s also Howard Hughes. Need more be said on that front?

Though these threads are there, it is not them that hold together these varied essays in my memory these few weeks later. Though I just wrote it out for you, I don’t think to myself, “those were essays about California,” or “those were essays about the eccentricities of man.” I think, “those were essays by Joan Didion.”

Similar to my experience with Ada Limón, one of the essays from this collection has tucked itself into one of the folds in my brain and won’t seem to come out. “On Morality” struck a chord for me immediately. I read it and I felt a connection to Didion—the type of moment where you feel like an author is taking words out of your head that you hadn’t realized were in there yet.

She begins with her assignment: to talk in the abstract about the concept of morality. Very quickly, however, she asserts that there is only one type of morality that she views as uncorrupted, and it is hyper-specific. Moral people do not leave a body alone in the desert, unguarded in the night. Moral people live according to one of the most basic promises we make: “we will try to retrieve our casualties, try not to abandon our dead to the coyotes.”

What she means by this, is that good and honest morality is simple and it is strict. Outside of our basic loyalties to the ones we love, it is arrogant to claim any kind of moral primacy, let alone to act upon those feelings or attempt in any way to subject others to the supposed superiority of your own conscience. She goes so far as to say that outside of the fundamental social code, there is no way of knowing what is “right” or “wrong,” “good” or “evil.” Outside of the fundamental social code being the key.

It is when people lose sight of that fundamental code that “questions of straightforward power (or survival) politics, questions of quite indifferent public policy, questions of almost anything: they are assigned these factitious moral burdens.” This is the problem we face as a society today and it’s one that seems to have raged unchecked for almost 60 years, since Didion wrote this piece in 1965. When people’s individualized (or even collective) fear, greed, preference, delusion masquerade as the moral imperative, “then is when the think whine of hysteria is heard in the land, and then is when we are in bad trouble.”

Joan! Soothsayer extraordinaire.

Given recent events, it should go without saying in a conversation about morality, that beheading babies, raping women and parading them bleeding through the streets, kidnapping children, and murdering civilians very much goes against fundamental loyalty to humanity’s most basic social and moral code. It is wrong, it is evil, and the people who want to talk about it in the abstract are morally depraved. I have been horrified to learn that it apparently does not go without saying, and I do not want to be misunderstood. So I have said it.

“trying to make sure I get straight A’s on the English papers that I assign myself every week” truer words have never been spoken. And you’ve convinced me to pick Didion back up.

Amazing!!!!!! You make the world a better place with your words.