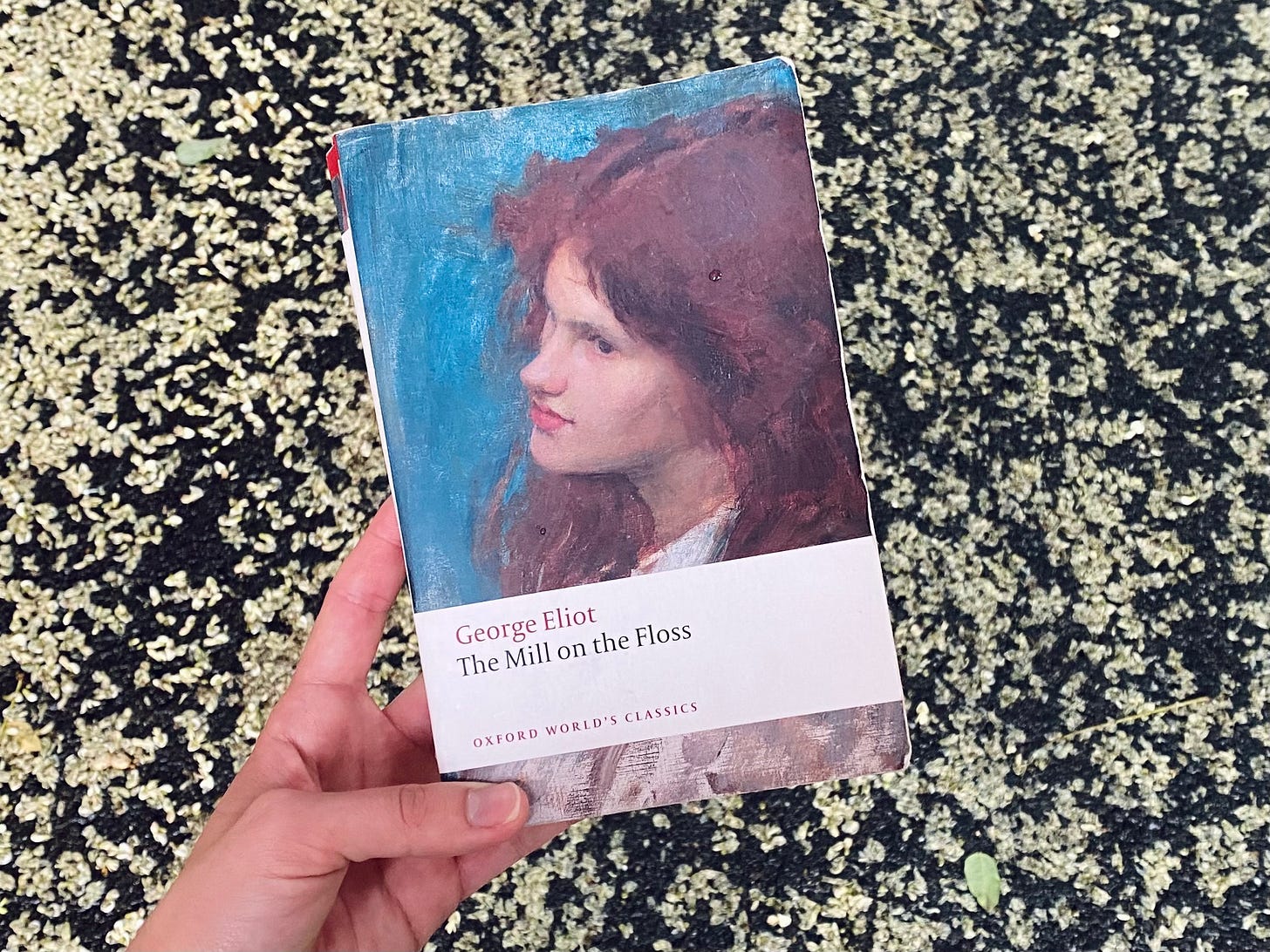

I Love You, George Eliot

The Mill on the Floss does NOT disappoint. This woman does NOT miss.

For those who weren’t around when I wrote about Silas Marner, I’m a George Eliot supremacist. I literally adore her. I realized this year that I have accidentally read one novel by her every year for five years straight. Isn’t that delightful!? First was Adam Bede which I didn’t actually read. Then Daniel Deronda, then Middlemarch (best novel in the English language, bar none), then Silas Marner, and now The Mill on the Floss. Only two more years until I start re-reading! Well…three if you don’t count Adam Bede as a re-read, which you shouldn’t.

But I digress! This post isn’t about Eliot’s entire bibliography. That would require more metaphorical pages than I currently have at my metaphorical disposal. This week, it’s all about The Mill on the Floss, and there is MUCH to discuss. The ecstasies and heartbreaks of early childhood, what it means to get an ‘education,’ pride, prejudice and bull-headedness. Ridiculous relatives, financial ruin, intellectual curiosity, selfishness and self-sacrifice. Familial and romantic love, pulling oneself up by the bootstraps, being swept away in the current, and trying to row against it. Perseverance, penance, gossip, gender, floods, forgiveness and death.

Considered as Eliot’s most provincial novel, The Mill on the Floss tells the story of the Tulliver family. Mr. Tulliver has a mill (Dorlcote Mill) that belonged to his father and his father’s father before that. Mrs. Tulliver has three sisters who are judgmental, overbearing and self-righteous. Together, Mr. and Mrs. Tulliver have two children. Tom who is stubborn and loves justice, and Maggie, who is stubborn and loves being loved.

Dorlcote Mill, which is on the Floss, is part of a little town called St Ogg’s. When the book opens, Maggie is nine. Tom, at twelve or thirteen, is home for break before he is sent off to a new school. Maggie is over the moon because she loves Tom more than anyone or anything. When he spurns her, as twelve year old boys are known to spurn their nine year old sisters, she feels as if her world is ending. The only thing that can make it all right again is the sweet embrace of forgiveness and the promises of love that come when she and Tom make up. And they always make up.

From these idyllic childhood scenes, we follow Maggie and Tom as he goes off to school, and then she goes off to school. They grow up, at least a little, and the natures that poked through in childhood begin to firm up. Then tragedy strikes when Mr. Tulliver loses an ill-advised, somewhat personally motivated lawsuit. The mill is lost and the Tullivers are bankrupt. The financial and social ramifications of this ruination spiderweb out like a cracked window, and Tom and Maggie grow up a bit more, a bit more quickly. They must figure out a way to support themselves and get used to their new place in society, while they grieve all that they have lost.

It’s not trivial in their lives, but in the grand scheme…it all sounds pretty provincial, right? Well, if my manic listing up above didn’t give you a hint already, allow me to put it more clearly: the Tullivers, and the mill, and St. Oggs—the provincial players and scene—are merely a lens through which Eliot examines the world at large. She zooms in so closely on the small people in the small town in order to show her non-provincial reader that his or her life is not the only kind of life there is. She zooms in to remind the sophisticated that their sophistication, somewhere down the line, relies upon the small stuff that makes up a simple miller’s life. She does it to show that the stuff that makes up a miller’s life is actually not so different at the core from the stuff that makes up her reader’s life.

The other thing I have not sufficiently made clear, with my insufficient summarizing of this big deep plot, is that this book is really about dear, sweet Maggie. One need not look further than our unforgettable heroine to understand the way that Eliot taps into universality of feeling without relying upon any universality of circumstance. Maggie is singular and recognizable at once.

In her childhood years, everyone is always lamenting how dark she is—her skin is brown and her hair is a thick, black, unruly mess. This compared (and it frequently is compared) with her cousin Lucy’s milky, porcelain complexion and blonde ringlets. It’s not just appearance though, Maggie won’t sit still, she is not quiet, she loves to read, and she comes home covered in dirt every time she jaunts outside (often). She does not mind like a good little girl should. She is the stormy sea to the placid garden pond of idealized Victorian girlhood. She is a darling little beast, though I don’t know if a contemporary reader would have agreed on the darling piece.

I said before that Maggie begins the novel as a stubborn little girl who wants to be loved, and that description is true, but it’s too superficial. Stronger words are in order. She is willful, and she is desperate to be acknowledged in any positive way. On top of this, she is completely and utterly unregulated emotionally. When something happens that upsets her, she runs up to the attic to pace, and fret, and talk to herself. She literally beats out her frustrations on an old wooden doll. Sometimes these frustrations are against others, like an overly critical aunt, but the most powerful fits for Maggie are always brought on by the sense that she has done wrong.

When Maggie, tired of being constantly bothered about how her hair won’t lay flat or curl right, decides to cut it all off, the “sense of clearness and freedom,” produced by the act does not last long:

"He [Tom] hurried downstairs and left poor Maggie to that bitter sense of the irrevocable which was almost an everyday experience of her small soul. She could see clearly enough, now the thing was done, that it was very foolish, and that she should have to hear and think more about her hair than ever; for Maggie rushed into her deeds with passionate impulse, and then saw not only their consequences, but what would have happened if they had not been done, with all the detail and exaggerated circumstance of an active imagination.” (61)

Poor Maggie. Emotional regulation is not an innate ability. We each of us are born with a release valve that has no stopper. We are hungry or tired, and we cry. As we gain consciousness, things don’t go our way, we are scared, or we feel pain, and we cry. Some people with an overactive emotional imagination like Maggie truly have a harder road to hoe than others. Everyone learns to stop up the outbursts and the tears over time, but it’s an easier lesson for someone who has dry eyes, if you catch my drift. Growing up means accepting that we cannot immediately act upon our feelings—that sometimes, we cannot act upon our feelings at all.

So how does Maggie progress with this learning and accepting? Well, she progresses, but it’s a hard fought war, and each battle produces its own anguish and leaves its own scars. Maggie is forever trying to do the right thing—to be a good, loving person. It rarely comes out right though, and she never does grow out of her childhood fervor for self-chastisement, whether the mistake is large or small. We watch on as Maggie learns to bear up under her powerful emotions and live with the consequences of her actions. We watch as she wonders how to balance her own desires with doing what is right. It’s one of the core components of living life. It’s the work that we have to do every day. We read about Maggie, and we feel that she is us, and we are her. Or at least I did.

Really, Eliot’s ability to build a character is arguably the best thing about her writing even when it isn’t so meaning-of-life-y. I say arguably because you’ll catch me on another day arguing that something else is the best thing, and that’s ALLOWED. With a central character like Maggie, the construction reaches incredible depths, but even with more minor characters, or those who don’t have as much interiority, Eliot knocks it out of the park. With just a stroke of the pen she brings people to life with simultaneous specificity and generality. Each character is distinctly their own person, but they are also people we know in our own lives.

At one point we are given a peak into the home life of Aunt Glegg—one of those overbearing sisters—and Eliot exercises these powers to the utmost. On Mr. Glegg’s ability to tolerate his intolerable wife, our narrator muses: “I am not sure that he would not have longed for the quarreling again, if it had ceased for an entire week; and it is certain that an quiescent mild wife would have left his meditations comparatively jejune and barren of mystery.” When that quarrelsome, mysterious wife enters the scene, we learn about one of her special talents: “People who seem to enjoy their ill-temper have a way of keeping it in fine condition by inflicting privations on themselves. That was Mrs. Glegg’s way; she made her tea weaker than usual this morning and declined butter.”

Who doesn’t know a couple in constant argument? People stay together for all kinds of reasons, but we’ve all seen the case where the only possible explanation is one party’s desire or need for excitement. And who hasn’t intentionally made their own bad mood worse just for the perverse pleasure of having a really terrible day?

These little social portraits also show Eliot’s gift for humor. She is really funny when she wants to be! Which is nice, because a little giggle here and there provides some welcome relief from the heavier topics that flow through the novel. And that brings me around to the elephant in the room, being an elephant both because it is HEAVY, and because it’s impossible not to mention: The Ending. I will not actually say anything about it because I don’t want to spoil it. However, I audibly gasped and may have also said “you’ve got to be kidding me.”

Suffice it to say, I simply would NOT tolerate an ending like this from any other author. George Eliot is the only person living or dead who could not only induce me to tolerate it, but also to begrudgingly admit that I really, really like it. If you have read The Mill on the Floss, please get in touch so that we can talk about how much we love and hate Eliot for doing that to us!!!!

A note on reading George Eliot:

It would be a straight lie to say that anything by Eliot is easy reading. It’s not. Her syntax, vocabulary, references & allusions—all of it—are 19th century. But it’s not Shakespeare, babe! Although maybe one day I’ll write a post about how shockingly readable Shakespeare is too. I should say, it’s not Beowulf, babe! George Eliot writes in modern English. She cooks with the same ingredients we cook with now. The seasoning is just a little different. Here are my reading tips for anyone who might be intimidated (or whatever) by Eliot:

Go slowly! It takes longer to read Eliot, especially in the beginning. You must get acquainted with her cadence. Once you are, you won’t have to use as much active brain power to untangle the sentences. It’ll still be slow, but that’s okay!

Block out bigger chunks of time to read. If you only read for 20 minutes at a time, you’ll only read 10 pages at a time (or 8, or 12), and you’ll never be able to sink into the writing and get comfortable

Eliot sometimes dives into things like the Catholic question or whether the Duke of Wellington is good or bad (??? your guess is as good as mine). While I’m sure the context would be interesting, I’m not an expert on Victorian history, I’m not in an English class, and I have a full time job. I don’t have the time to make sure that I have an in depth understanding of every cultural, political, social tidbit that Eliot decides to include, but I still want to read and enjoy her writing. Many editions have explanatory notes that can shed light on the obscure. Use them if they’re helpful, or skip them if flipping back and forth to the notes section makes you feel like you're reading a textbook instead of a novel. Maybe this is a bad take, but I think it’s sometimes okay to skate through these bits. I’m not advocating for skimming or skipping—I still think it’s important to read every word because Eliot’s words are gold! I’m just saying it’s not always worth getting bogged down in the details. Read on!

I think I’ve answered my own question about whether I should read this having read your great post. I’m going to have to!! The density has been putting me off tackling it - this and middlemarch, which has also been looking down from the shelf disapprovingly for the last six months. I remember reading an analysis somewhere about Eliot, and how she mixed in contemporary critiques of celebrity which could - to the modern reader - be largely ignored without detracting from the novel; you touch on that in your review. I’m going to have to follow your advice and block out longer periods of time to pick them up and get on with it! But the question then is - Middlemarch or The Mill on the Foss first??

I love this and can't wait to read the Mill on the Floss (once again after about 70 years) Love, Gramma Bonnie