Justice for May Welland!!!!!!

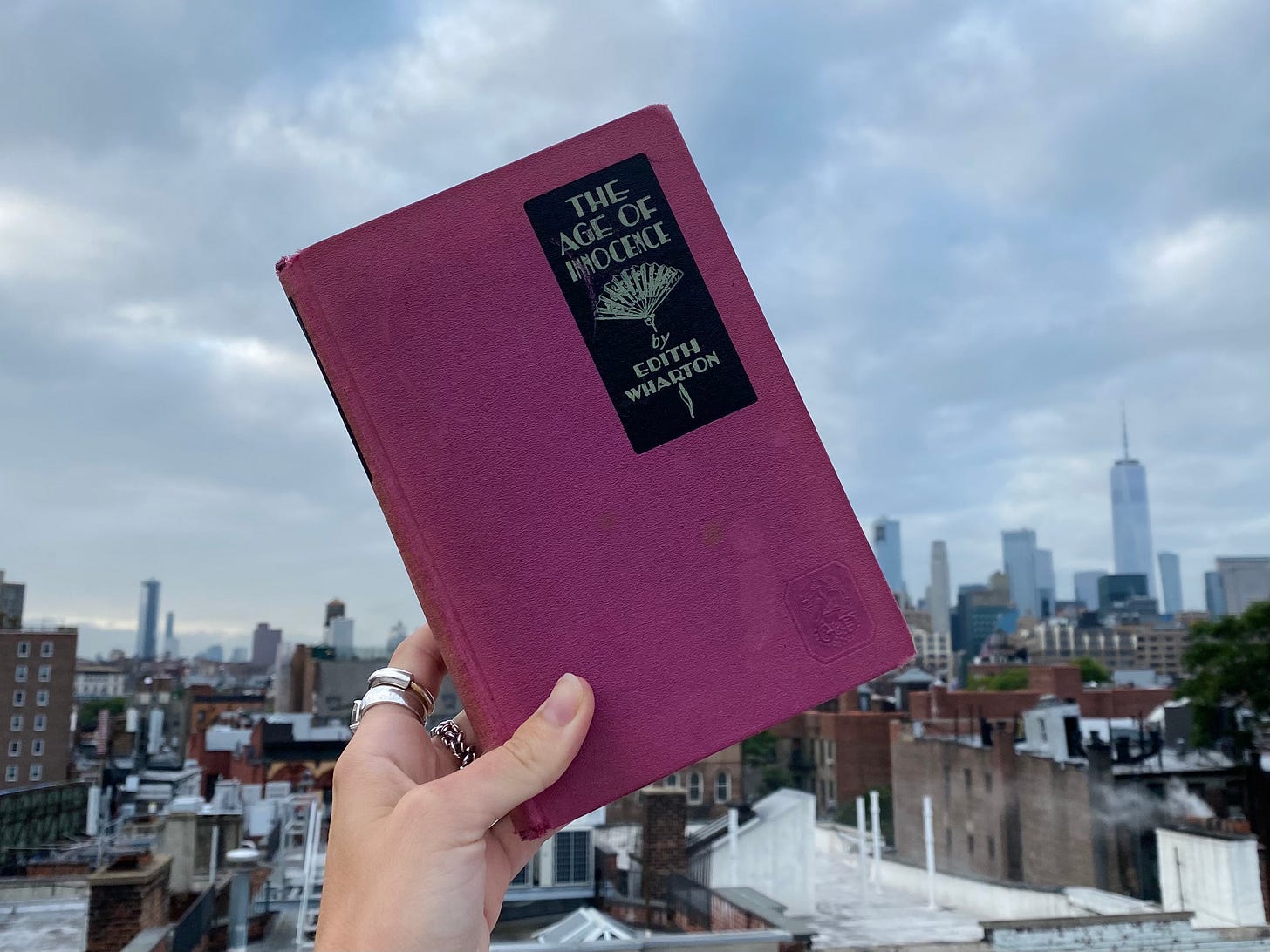

The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton

Happy September, dear readers! Another month, another fantastic (at least my dad thinks so) episode of Something We Read, the podcast I host with my sister, Kathryn. In August, we read The Age of Innocence, which was, delightfully after July’s blunder, a total smash success! All the people who have been saying that this is a really good book for the past 100 years have been seriously onto something.

The post ahead will include ~light~ spoilers. Nothing crazy!! Don’t worry!! I’m working on rebuilding trust after last month. We did a really good job on the podcast, so if you want a truly spoiler-free experience, just listen. Then come back and read this after you’ve read the novel. I do still want you to read this. So I’m not just shouting into the void.

If you’re okay with a little hint of this and a hint of that—we are talking about a book in the public domain, after all—then carry on! It’s long because I had fun writing it. I hope that will also mean it’s fun to read. I never can tell. Xx

The Age of Innocence is often perceived as a study of society. The forces at play, the rules to be followed, the consequences of those rules when broken and even when obeyed. And it is that, of course, otherwise people wouldn’t say it was. BUT, I had the unique experience of reading this novel without any introductory material, which meant I wasn’t reading with that preexisting frame in mind. It meant that for me, this novel read as a study of three characters. Three characters living in a very specific society, yes, but also just three characters for the sake of themselves.

Newland, Ellen and May.

The Age of Innocence is the story of their love triangle, though the conceit of the novel is that May is unaware of her participation in said love triangle. More on that later. At open, Ellen, or the Countess Olenska, has arrived in New York City after fleeing her disastrous marriage (to a European Count) under somewhat dubious circumstances.

Her New York family, which is old and grand and well-established, must now undertake the precarious task of bringing her back into society. It will require tact and precision, since running away from one’s husband is…just not done, dear, no matter the circumstances. Part of Ellen’s New York family includes the apple of the city’s eye—the Diana-esque May Welland, all but engaged to none other than our Newland Archer.

Newland is eager to get married as soon as possible anyway, and urges May to announce their engagement sooner than planned. This way, his proposal to May will serve as a tacit endorsement of Ellen and soften any potential reputational blow that the Coutness’s arrival might bring down upon her broader clan. If a distinguished and respectable man like Newland Archer takes no issue with Ellen’s presence, then who could?

All under the guise of helping to ease her societal re-entry and safeguard against any scandalous harm done to May and her family, Newland begins to spend more time with Ellen. Predictably, they fall in love, but too late! Conscientious Newland has exerted enough pressure to not only bring the engagement up, but the marriage too.

For me, The Age of Innocence is the story of how three different people, raised primarily among the same set, live through this muddled situation they’ve gotten themselves into.

I’ll begin with Newland, since he serves as our primary narrative lens. And to get it over with. I won’t beat around the bush—he annoyed me very nearly out of my wits! I partly blame the aforementioned fact that I did not have the introductory materials. I did not realize that he was meant to be a sympathetic character until the very end. Which made it difficult for me to enjoy the ending. But seeing that aside, despite the fact that I found him irritating at every turn, it would, however, be extreme to say that I didn’t sympathize with him at all. I did. Let us take stock:

He’s a member of the stifling New York society into which he was born and within which he was raised. He’s been immersed in the balmy bathtub waters of Taste and Manners and The Way It’s Done his whole life. One need look no further than his mother to get an idea of what he’s up against in this regard. Though he rolls his eyes at her, he was raised by her.

In marrying May, he’s doing what he was raised to do. More than that, he’s doing what he believes to be the right thing to do based on his upbringing. It’s not just rote action; he wants it. He is naturally attracted to May—both physically to her beauty, and socially to what she can offer him on a broader scale as a wife. He does not want her to be a “simpleton” and plans to develop her with his “enlightening companionship,” but he has little hope that she will prove to be his intellectual or emotional equal in marriage.

There are few examples of equal marriages within the novel, so why should he expect one? The one exception, in my humble opinion, would be the Van Der Luydens, who he respects, but also views as the obsolescent upholders of a set of societal norms that is effectively, or should soon be, out the window. Besides, he doesn’t really view this perceived lack of equality between himself and May as something to lament until Ellen shows up on the scene.

Which leads me to the real way in which I was able to sympathize with him as a character. You see, to me, much more than being a representative figure, beaten down and controlled by the milieu with which he associates, he’s simply a man beaten down and controlled by love. And lust, though to a lesser degree. He’s in the throes of it, and he is made, yes, deeply annoying by it—as only a man in love without capacity to act can be. I did root for him and Ellen in a way.

What is it that keeps him, a man in every position of power, from doing what he wants and getting what he wants (maybe what he deserves, though you’d have to convince me that he deserves Ellen)? I can see it as proof that even a man such as him was unable to exert his agency in a society as stifling as old New York, I’m just not sure I fully buy it as that.

Which brings us to Ellen. Ellen who more than exerts her agency, many times over. The first and most striking time, when she fled her husband, she was, of course, operating outside of the Puritanical New York regime (though Wharton paints religion as an afterthought in the novel, it’s certainly there). She also had a little bit of help. Through the rest of the novel, though, she exerts her agency within the regime and without any help, over and over.

A common refrain throughout the novel is how much more liberal Europe is—particularly in regard to who is suitable society, but also in regard to how those in society behave. Artists, actresses, opera singers, writers. Promiscuity and open affairs, with these artists and amongst them, These people and actions are decidedly below the order in New York. But Ellen is used to the circles she’s used to. With her taste for entertainment and culture and the arts, she threatens to upturn the apple cart. To come into this tight laced community, daring to disregard their codes and strictures.

She already occupies a very precarious space. She could be the dangerous woman. She has broken the rules, and she does not appear to repent, at least certainly not at the outset. However, she’s not thrown aside or asunder. How is this possible? Well, her very existence in this novel is provided for by the loosening of societal moral codes. As I hinted at in the podcast, look to the literature of ~50 years prior and you won’t see any Ellen Olenskas. That is, unless they’re getting pregnant and dying, or getting pregnant and getting thee-selves to the nunnery.

As this slightly more modern version of the dangerous woman, I was prepared for Ellen to disregard societal norms entirely. To wreak havoc and maybe even get away with it a little. At least that’s one way Wharton could have played it. Instead though, Ellen’s character displays what I would classify as an admirable self control—one that results in a mastery of the situation she’s in. She’s determined to do the right thing, insofar as she can do it. And while this could be viewed as her corseting herself back up to fit into a restrictive system after living in a free one, I don’t think that’s quite the argument Wharton is making. Loose, free Europe is not the ideal or the bastion. It’s what Ellen is running from. A society with too little structure has its issues too.

Besides, I view Ellen’s struggle to do the right thing as intrinsically motivated as much as it is societally motivated. I give her that credit. Namely, though deeply in love with him, she does the required work of keeping Newland at bay. She does the excruciating work of hiding her true feelings, of not letting him fully see.

Because she knows there is no way forward, she repeatedly removes herself from his vicinity. She stays out of his reach. She knows he is not strong enough, so she must be. Though controlled by the strictures of society, though in the throes of love, she maintains control over her soul and spirit, and you simply cannot convince me that there’s no power in that.

Which leads me, finally, to May—the most interesting and most neglected of the three.

From the start, she is framed primarily as a visual entity through Newland’s eyes. As he observes her in her opera box from across the way as she intently takes in the scene on stage, he notices her “warm pink” blush, her “fair braids,” and the “young slope of her breast.” He “contemplate[s] her absorbed young face with a thrill of possessorship.”

When he does consider her intellectual or emotional inner life, he believes her to be good and pure. Selfless in her treatment of her disgraced cousin, and even more innocent in the comparative presence of that disgrace. He imagines himself enlightening her in more ways than one after their marriage—drawing pretty pictures on a blank canvas. He thinks of her repeatedly as having “serious eyes” yet maintains the position that her developing but still “shy interest in books and ideas,” is owed entirely to his guidance.

In reality, the seriousness in her eyes reflects a greater depth. A depth that was already there before Newland showed up! A depth that I believe would be visible, or perhaps more fittingly, audible—through the things May actually says out loud—to anyone paying attention. She is an attentive and thoughtful person.

Even at the very start, she wants Newland to be the one to tell Ellen of their engagement. This, when Newland still believes himself to be repulsed by the runaway wife. But though May is innocent as to specifics and mechanics, she’s emotionally attuned. She’s not a fool. She continues to ask Newland about Ellen. The says that it’s “dear” of Newland to send Ellen flowers, but “odd” of Ellen not to mention it. So on and so forth.

And then—of course, the most striking and most obvious scene, when Newland rushes down to St. Augustine to escape the feelings he’s incapable of dealing with. He kisses her roughly, and she’s taken aback. He asks to move their wedding up (again), and she knows something isn’t right. She says, “Let us talk frankly, Newland.” She asks him if there is someone else.

And to give him credit, the sheer force of her exposing herself in this way does make an impression on him. He recognizes that there is a greater depth in his betrothed. He sees it and is exhilarated by it. But instead of seizing it and stoking it, by introducing a new honesty on his own half as well, he snuffs it out.

He cannot even fathom that May is aware of his attraction as it may express itself in directions other than her own. Yes, she misses the mark by latching onto a previous affair of his, but her sense that his attentions are elsewhere is spot on. She may even know on a deeper level that the person she’s truly worried about is Ellen, not this other woman. At this stage, Newland is in denial about his feelings for Ellen anyway, so this specter from his past is a welcome diversion. He is able to say No, dear! That’s behind me, even though he too knows that something more dangerous is brewing. Either which way, May extends a shaking hand, and he brushes it away.

And THEN, as the novel progresses, as they prepare for their marriage and even get well into it, Newland repeatedly laments that the flash of power he witnessed in May that day in St. Augustine has failed to reproduce itself. He convinces himself that the “womanly eminence” that characterized that episode must not really be there after all. In actuality, any subsequent stifling of emotion on May’s part after that fissure is less a reflection of her true nature than it is of his decision (though of course it was in the heat of the moment, and he’s just human too) to reject her offer of true mutual understanding.

As the situation between Newland and Ellen becomes increasingly dire, May becomes increasingly desperate. In a position of little power, both through the societal lens, and I believe more importantly, through the lens of a lover disadvantaged, May begins to do what she can. She contrives, often unsuccessfully, to keep Newland from seeing Ellen. If they see each other, she makes sure to approve of their meetings. If it’s going to happen, she’ll even be the one to suggest it. If it’s going to happen, she’ll certainly pay a visit to Ellen afterwards. She begins to pay attention to what Newland says. She knows where he’s supposed to be when and she wields her knowledge.

Lacking the even ground for communication that she tried to create initially, and yes perhaps being more comfortable in the old grooves of “tacit understanding” that she was raised to recognize, she can only express her concern by throwing her arms around his neck and crying, “you haven’t kissed me today,” in what is truly the most excruciating scene of the novel. He’s too wrapped up in his own whirlwind to recognize her pleas.

But much like Ellen’s ultimate control over her romance with Newland, May figures out how to control her situation as well. She plays her trump card. She goes right ahead and gets herself pregnant. Of course, one can question whether what she “got” through this maneuver was really what she wanted—or what she deserved. But within the bounds of her life, and following the “dictates of Taste,” I’d say that she did.

So what’s the point, Eve? If you’ve made it this far, after all that, I’ll put a bow on my ramblings by saying this: women are better at emotional processing and decision making than men are. No matter what society looks like. This strength, that is inherent to the female psyche, is a great source of power, regardless of the environs.

& justice for MAY WELLAND!!!!!

Love you, bye.

I just finished this book and like you I did not read any commentary about it before starting. I also came to the same conclusion as you did that May Welland is much smarter than she’s given credit for.

Yesss loved this! I recently finished rereading it for the third time and was so fascinated this time around by May and her quiet cunning. Newland’s caught up with pre-existing notions from his upbringing and society, and he’s repeatedly surprised by Ellen’s behaviour and repeatedly wrong about May’s insight. When I read it this time, I felt that May’s asking about his previous affair was definitely a diversion - I think she was starting to suspect re Ellen and used his previous affair as an opening for him to be truthful. When he wasn’t, that was her warning - two days after Newland gets back to New York, May has convinced her parents to speed up the engagement. Then the similar thing about announcing her pregnancy to Ellen before she even knew for sure (not quite as subtle but inescapably effective) - she 100% knew what was up and her intercepts come at *just* the right moment. Godddd this book is so good I could go on about it for hours lol. Absolutely justice for May