Last Month’s Reads (again)

January 2026 (pt. 2)

Picking up where I last left off, after reading The Little Friend, I had reached the middle of the month, and felt myself in a particularly precarious situation. What could I read next that would measure up? I was on such a (four book) roll so far, but could it last? On top of that, I was headed to the Bahamas for a wedding. While I would presumably not be reading once I got there, I had connections on the way there and back that would give me plenty of time (so much more time than I could have ever guessed). Since I’m not allowed to buy emergency books in airport Hudson Newses, this meant that to be safe, I actually needed to choose my next three books.

To start, I thought it best to pick something that couldn’t be measured directly against Tartt. The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje is described as a “spellbinding web of dreams” on the front cover. This seemed promising in terms of incomparability with Tartt’s precision. It also won the Booker in 1992 when it was published, which made it promising in terms of general quality of writing. Thanks to a delay in Charlotte (my least favorite airport on the planet including the ones I haven’t been to), I finished it before we even arrived in Harbor Island.

The novel opens in an almost abandoned villa in the hills outside of Florence. Set during WWII in the immediate aftermath of German surrender, it focuses on four very different characters brought together by the strange circumstances of war. The villa served as a hospital at the height of the Italian campaign, but now hosts only one patient, the English patient, burned beyond recognition and unable to move, and Hana, the Canadian nurse who for reasons even she may not fully understand, refuses to leave him. Onto the scene come two additional characters: Caravaggio, a thief, spy, and, in what feels like impossible coincidence, friend of Hana’s father who she knew in her youth in Toronto, and Kip, a Sikh sapper for the Allied forces, responsible for diffusing and dismantling the network of tripwires, mines and unexploded artillery left by the Germans on their retreat.

Slowly, in disordered and dreamy vignettes, we learn about each character’s past. Particularly and most compellingly, the English patient, who was a desert explorer around the time of the North African campaign, which I didn’t even know was a thing. Caravaggio becomes convinced that the burned man isn’t English at all, but a Hungarian count who cooperated with German forces in Cairo. The burned man claims not to remember who he is, but slowly a grand love story unfolds in the Sahara through the fragmentary stories he shares when he is on enough morphine to talk but not enough to sleep.

I found the descriptions of the desert, and of what it takes to plan and execute an expedition in that most unforgiving of terrains absolutely fascinating. The segments of the novel dedicated to Kip’s history and work as a sapper were also captivating. There was a satisfying parallel between the English patient and Kip, in the danger of their chosen work and the precision required of them, and also in the love stories that unfold—one in memory and one in present day—for each of them.

It was only a few months after German surrender that the US dropped two atomic bombs in Japan ending the war, so I don’t consider it a spoiler to say that the same thing happens in the novel, jolting our four characters in the Florentine hills out of their fragile equilibrium. When I was reading, suspended as I was in Ondaatje’s dreamy world, it felt a bit like he used Hiroshima and Nagasaki to wrap up his story, if not neatly, then whatever the violent and horrible version of neatly would be. It’s not fair to hold this against him, since it’s what really happened and I think he rendered believable reactions for each of his characters. I was particularly struck by a line Hana writes in a letter home in the days following: “From now on I believe the personal will forever be at war with the public.”

Next up, I picked up The Hours by Michael Cunningham. I bought this book years ago at the Strand, somehow without realizing that it was about Virginia Woolf. The first time I tried to read it, I decided I should really read Mrs. Dalloway again beforehand. I use this method to put off books with some frequency (see Demon Copperhead, James, etc.). Last month, however, I decided that I was familiar enough with Woolf and remembered Dalloway well enough to read it anyway. It won a Pulitzer when it was published, so I felt sufficiently confident that it wouldn’t be bad…

And it wasn’t bad. I know that it wasn’t. But if I felt the end of The English Patient was un petit the easy way to end things, I found the beginning of The Hours horribly cheap. Namely, in the first chapter, Cunningham recounts Virginia Woolf’s suicide from her perspective. And I know that Virginia Woolf doesn’t need me to protect her—she’s public domain—but I didn’t find Cunningham’s handling of Woolf to be as deft or honorable as his reviewers apparently did.

I didn’t let my initial distaste for the project generally stop me though. This was the book I brought, so this was the book I’d read, and Woolf’s timeline is only one of three. In alternating chapters, we are with her in 1923 in the suburbs of London, with young housewife, Laura Brown, in 1949 Los Angeles, with poetic muse Clarissa Vaughan in 1999 Greenwich Village. Each of these women leads what is an ostensibly fulfilling life, but each is quietly unfulfilled.

Cunningham emulates Woolf’s signature style, floating in and out of the minds of his characters. They move through the worlds, but their minds move at a different pace, in a different place. His emulation is sometimes beautifully successful and sometimes feels like the output from a freshman year creative writing seminar—overly flowery or derivative.

The same applies with his numerous references to Woolf’s life and work. The novel takes place over the course of a single day like Mrs. Dalloway. Clarissa Vaughn is throwing a party that evening like Mrs. Dalloway. She decides to go out for flowers in the morning, like Mrs. Dalloway. The party is for her closest friend, Richard, an acclaimed poet who has affectionately referred to her as Mrs. Dalloway since they met in college.

Laura Brown is reading Mrs. Dalloway. She reads to escape the creeping ennui that she knows she shouldn’t feel with her American dream, World War II veteran husband and charming young son, Richie. Clarissa is bisexual and in a long-term relationship with a woman named Sally. Laura kisses her neighbor Kitty in a fraught moment sitting at the kitchen table. The representation of lesbian relationships and curiosities is a clear homage to Woolf’s own sexuality.

Some of these connections just feel like they’re there to remind you that this is a novel about Virginia Woolf-like the names, almost all pulled out of Mrs. Dalloway. Others are more subtle and meaningful. I appreciated the temporal grounding—as Woolf grapples (in her own life and through Mrs. Dalloway) with the aftermath of WWI, so Laura occupies a post WWII world, and Clarissa navigates the carnage of the AIDS epidemic. Cunningham’s thesis, that life is made up of the profound mundane, and that the small moments can contain an ecstasy that compensates for life’s difficulties and disappointments, is lifted from Woolf as well. He pulls it across time, into the present day, but I’m just not sure he really needed to. The novel is homage (respectable enough, though I still find I’m irked by the suicide chapter), but it is not expansion.

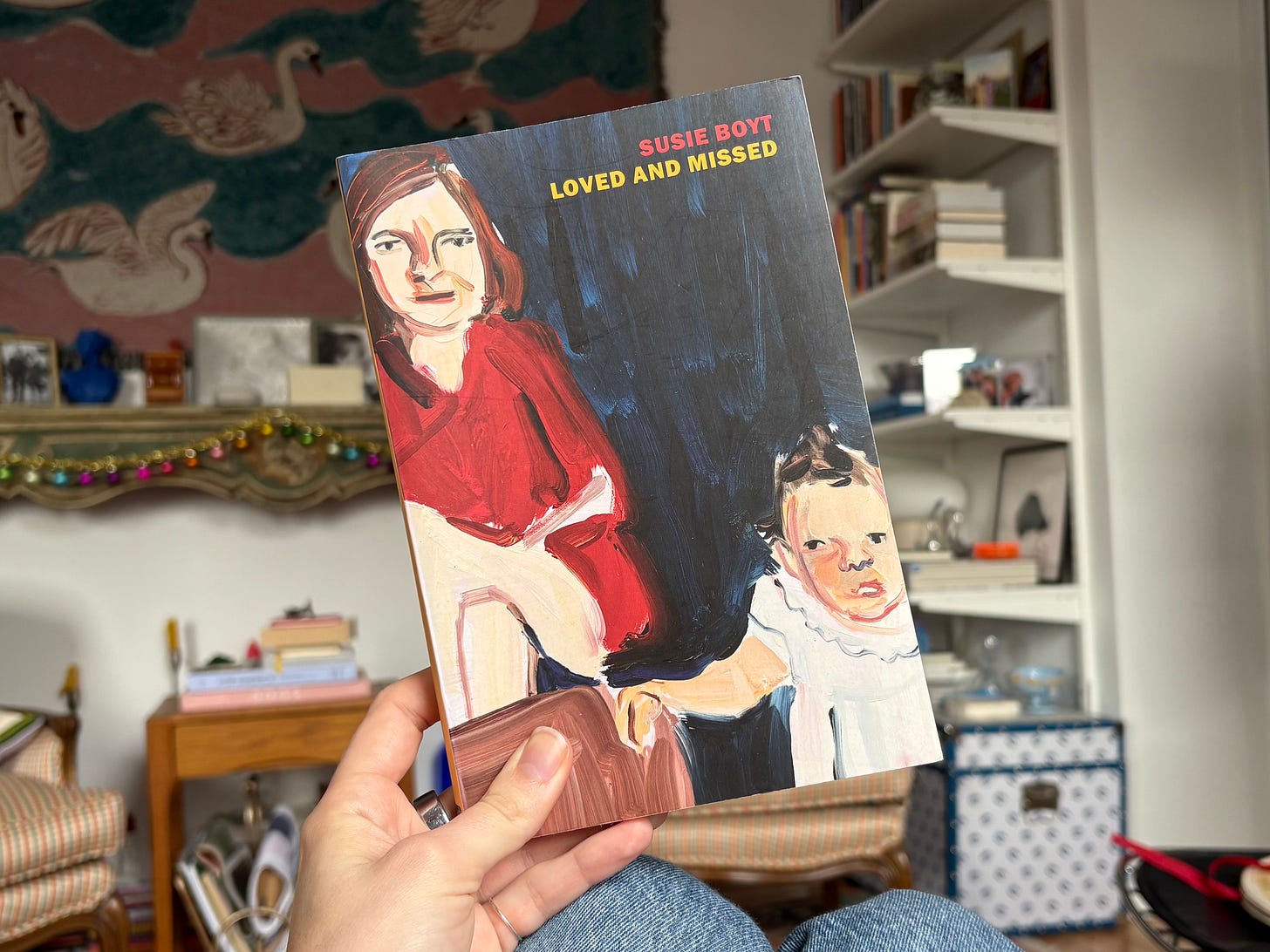

Due to truly harrowing travel complications on our return, I finished The Hours in a Bahamian airport I never intended to visit, a full 24 hours after I should have been home in New York. Thankfully, I had my backup backup book at the ready: Loved and Missed by Susie Boyt, another New York Review Book that I’ve heard wonderful things about from several trusted sources that I can’t remember or track down now. I didn’t get very far into this one before passing out, finally home in my bed at 2am. But when I picked it back up, I was in for a real treat.

Our main character and narrator is Ruth. Ruth has one daughter named Eleanor who is a drug addict. Eleanor in turn has one daughter, who she names Lily. Ruth tries to decode what Eleanor might need or want—tries to stay away when she feels she’s not wanted, tries to keep in touch, give some money here, bring some food there, but whatever language it is that Eleanor now speaks, Ruth can’t quite decode it. Eleanor lives in an apartment that Ruth owns, as do a cast of rotating drifters. One afternoon, when Ruth stops by with a roast chicken, she walks into the bedroom to take a look around and finds a man who has died of an overdoes laying on the bed, covered in blankets. She grabs Lily in the general panic that follows her discovery and flees.

From there on, Loved and Missed is a novel of everyday affection. Lily is a balm to Ruth’s suffering in her very existence, in her sweetness. She is also a second chance for Ruth, who blames herself for Eleanor’s situation. The narrative style, which is a simple first person takes on something extra—not as though Ruth is thinking, not as though Ruth is writing a record, but as if she is speaking out loud to herself. In a very short amount of time, you feel quite connected to her—and when elements of her past are revealed it feels as though you have become privy to something she’s been hiding, not from you, but from herself.

The novel is sweet, funny and devastating—all of that quietly. I found myself waiting always for the other shoe to drop, for Eleanor to come claim her daughter, to die, to do something horrible. For Lily to become unhappy, bitter, resentful. But it’s not a book of conflict—aside from the conflicts that Ruth has privately with herself. I found it to be a striking portrait of how one woman comes to live with herself, what she’s done and what she hasn’t done. The end came unexpectedly and was extremely well executed.

Boyt has published seven novels, of which Loved and Missed is the seventh, and first to be published in the US. I will be getting in touch with UK-based contacts to procure additional material by her as soon as I am legally allowed.

I didn’t feel like anything else contemporary after Loved and Missed, so I plucked Washington Square—a novel serialized by Henry James starting in 1879–off the shelf. I started reading it on a whim, kind of not sure if I would finish it or choose something else instead, only to find myself totally captivated.

A few contributing factors to my captivation: Henry James is a master of the sentence, Henry James is funny, and I can’t really figure out just what Henry James is trying to do. In Washington Square, he gives us a not particularly compelling heroine to root for. Our wry narrator tells us that Catherine Sloper “was a healthy, well-grown child, without a trace of her mother’s beauty. She was not ugly; she had simply a plain, dull, gentle countenance. The most that had ever been said for her was that she had a ‘nice’ face.”

She is, however, a heiress. Her mother, who died in childbirth with her, had a respectable fortune which her father was able to build upon considerably with his successful medical practice. Dr. Sloper is not a particularly loving father; though he takes pains to protect Catherine and give her every advantage, he does not really love her. Catherine’s paternal aunt Lavinia who has lived with the Slopers since the death of Mrs. Sloper is portrayed as something of a foolish, self-involved woman, and meddles in Catherine’s affairs to ill-effect.

What are those affairs? The appearance of one Morris Townsend, beautiful and charming good for nothing in search of, well, a fortune. Catherine proves to be an attractive target, but when Dr. Sloper catches wind of the budding relationship between Catherine and Morris, he is unequivocal in his disapproval, threatening even to disinherit Catherine should she choose to go against his wishes and marry Morris. In his stubbornness on the matter, there is a curious combination of true protectiveness—he does not wish for his daughter to end up with a man who will spend her fortune without making anything of himself—and a perverse impulse to insult and downrate his daughter.

I won’t spoil the ending, but it reminded me of Daisy Miller (the other James novel I’ve read) in that it is simultaneously tragic and totally unsatisfying. Nonetheless, James’s writing is highly entertaining. In Washington Square in particular, there was something Austen-esque about his setup and his characterizations. Austen-esque, but significantly meaner. Mona Simpson sums it up well in a 2013 essay in the New Yorker when she says of James: “He borrows from melodrama, but lops off that genre’s gratifications, going realist on us at exactly the wrong moment. If Americans want a tragedy with a happy ending, Henry James delivers something more like a comedy with a haunting close.”

In summary, favorites in bold:

The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway - graceful & somewhat depressing

Play It As It Lays by Joan Didion - definitely depressing but in California

Ariane A Russian Girl by Claud Anet - insane

The Little Friend by Donna Tartt - so, so, so good

The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje - very good until the end

The Hours by Michael Cunningham - kind of like…how did this win a Pulitzer?

Loved and Missed by Susie Boyt - sweet, sad, funny

Washington Square by Henry James - Jane Austen but New York & meaner/sadder

That’s January! Back soon with more. Xx

i was reading your description of Washington Square and it sounded familiar… then i realized the movie The Heiress (1949) is based on it!!

I can’t even explain how invested I am in your project of reading backlist titles from your shelves!! And the reviews here were especially fun to read—I like the diary-esque approach to talking us through the circumstances of the reading. Loved & Missed and Washington Square are two favorites of mine, so I’m thrilled you liked them too. (And I picked up The Hours at a library book sale this weekend, then eventually guiltily put it back on the table and left it behind in favor of a few others—thank you for confirming for me that that was an ok choice in the end!)