Last Month’s Reads

January 2026 (pt. 1)

It’s been a month and a week since I bought a book, which is surely a record for me, and I’ve never read so much. I decided somewhat on a whim in December that I would embark on this little experiment, spurred only by a vague sense of embarrassment at the number of unread books languishing on my bookshelf. I thought it would be hard, which it is, particularly if I enter a bookstore, but it’s also fun.

I’m reading books that I’ve owned for years and loving them or liking them or thinking they’re fine, but I’m reading them. It’s nice to not have so much choice. I have to just pick something, and so I do, and then I read, and then repeat. I’ve picked well so far.

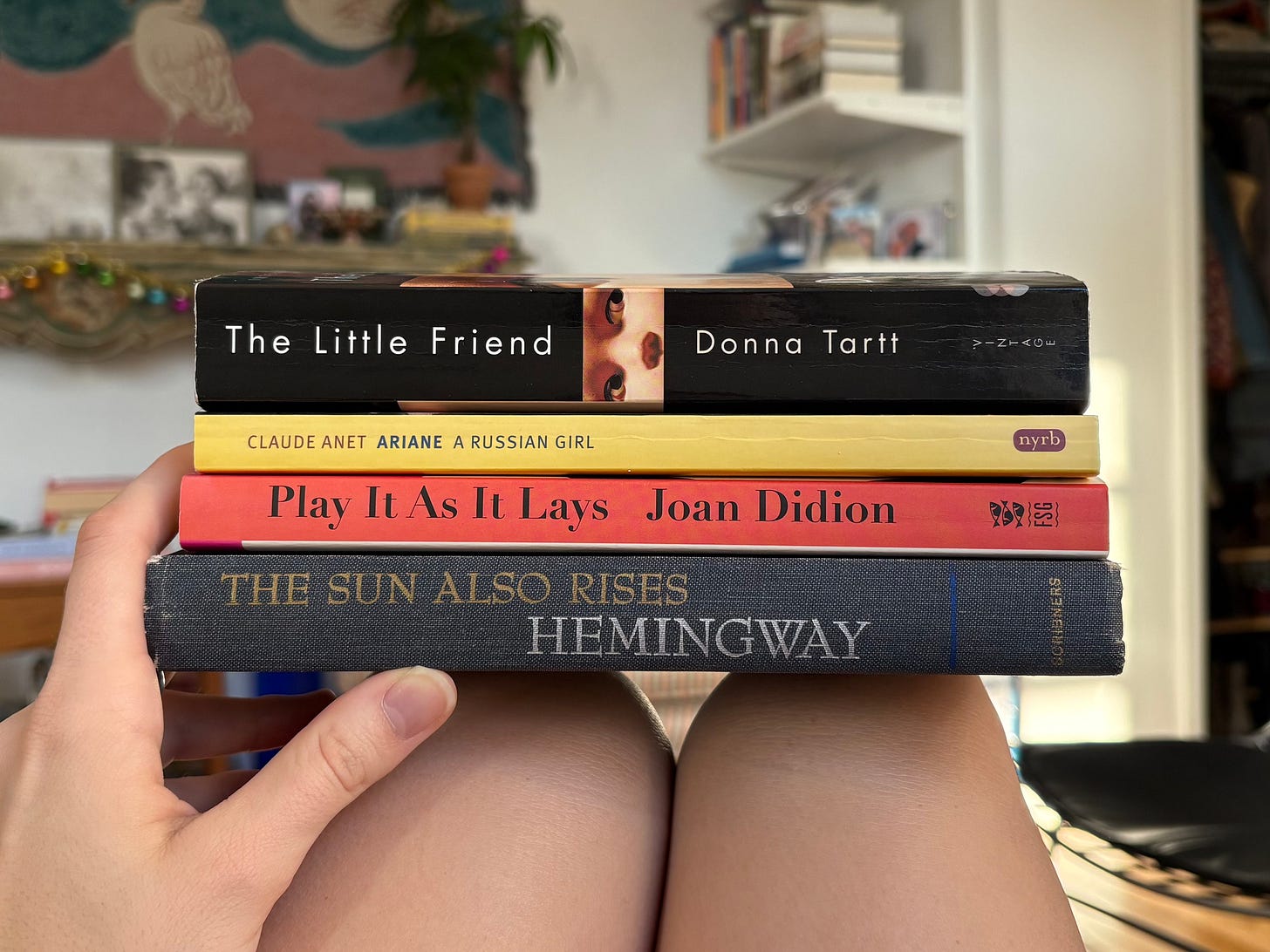

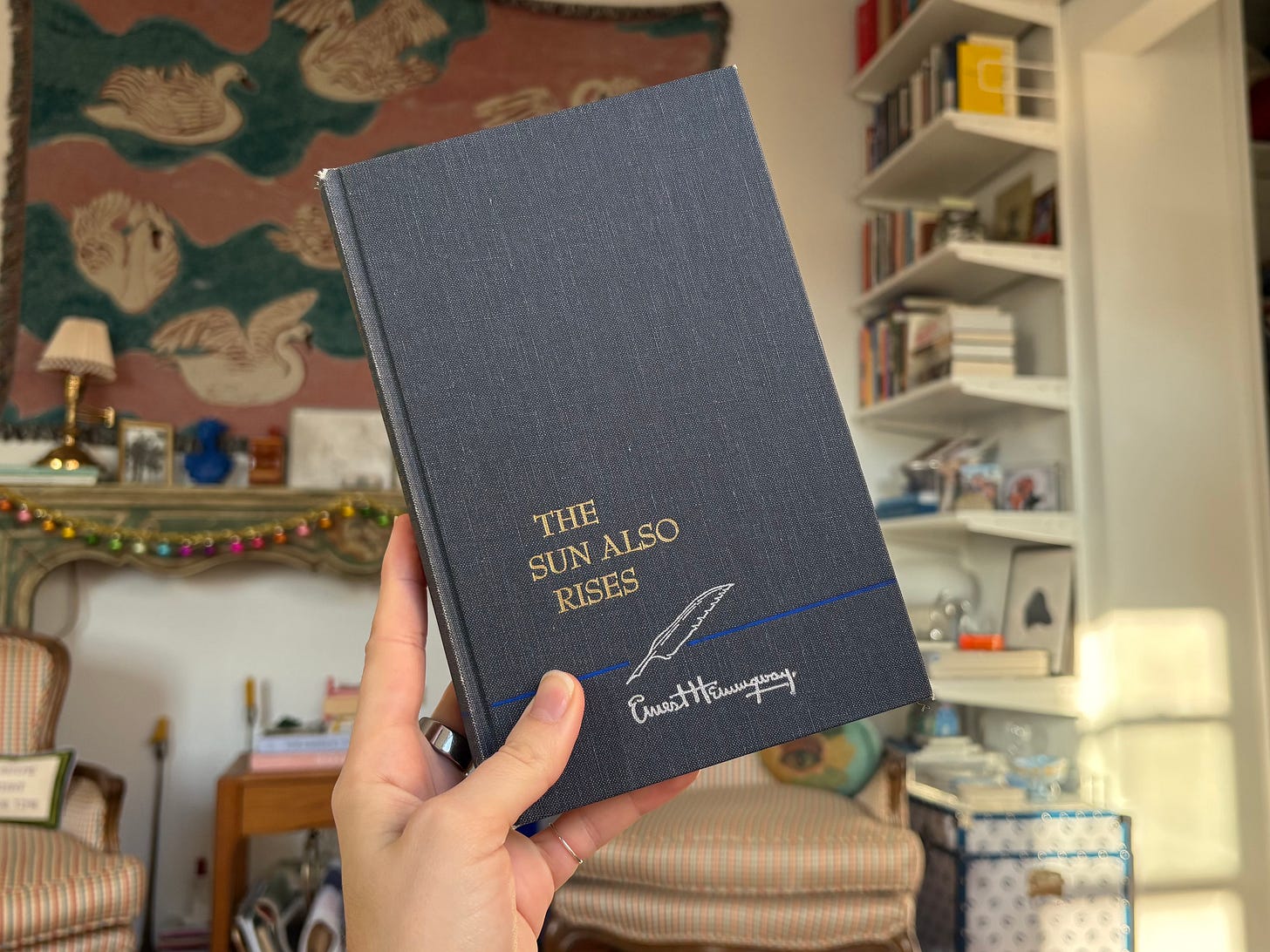

I started the month with The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway. A couple years ago, I found a pretty cloth bound Hemingway set at a thrift store. I thought, I should probably read Hemingway, so I bought them and then I didn’t read them. I picked The Sun Also Rises because of the three in the set (A Farewell to Arms, For Whom the Bell Tolls), its spine was the skinniest. It also happens to be Hemingway’s first novel, which is nice.

For those uninitiated (perhaps many, since Hemingway isn’t exactly fashionable at the moment), The Sun Also Rises follows Jake Barnes (American, veteran, journalist, expatriate in Paris) and a cast of characters that includes Lady Brett Ashley (divorcee, bobbed hair), Robert Cohen (Jewish), Bill Gordon (from New York), Mike Campbell (engaged to Brett), and eventually, once they all make it from Paris to Pamplona, Pedro Romero (bull fighter).

Nothing much happens. They go from the cafe to the restaurant to the bar and back drinking copious amounts of regionally appropriate alcohol. They misunderstand each other, offend each other and sometimes actually fight each other. They sometimes apologize and sometimes don’t. They are, in many ways, the embodiment of the “Lost Generation”—a term coined by Gertrude Stein in reference to Hemingway and his real life friends.

This lost-ness is most clear when the characters sit around trying to talk to each other (frequently). I say trying because Hemingway’s dialogue jumps and spins. the characters don’t listen to each other, they don’t say what they mean, or they do, but only in the middle of a conversation that’s got nothing to do with it. What everyone says about Hemingway is true. His language is simple and spare. What you hear less often (I think) is that it’s simultaneously very graceful, with something of the dancer in it: controlled with the odd dizzying moment.

I was also surprised to find, that while there is an overarching aimlessness to the whole crew, there is, in Jake, a real and grounded love of place. Hemingway said that there was no hero, no protagonist in The Sun Also Rises, but I’d say that it’s Jake—and so his caring attention to his surroundings suffuses the whole novel (and fights valiantly against the creeping (tempting?) aimlessness). I was particularly fond of the fly fishing section, and the descriptions of Montoya—the proprietor of Jake’s favorite hotel in Pamplona.

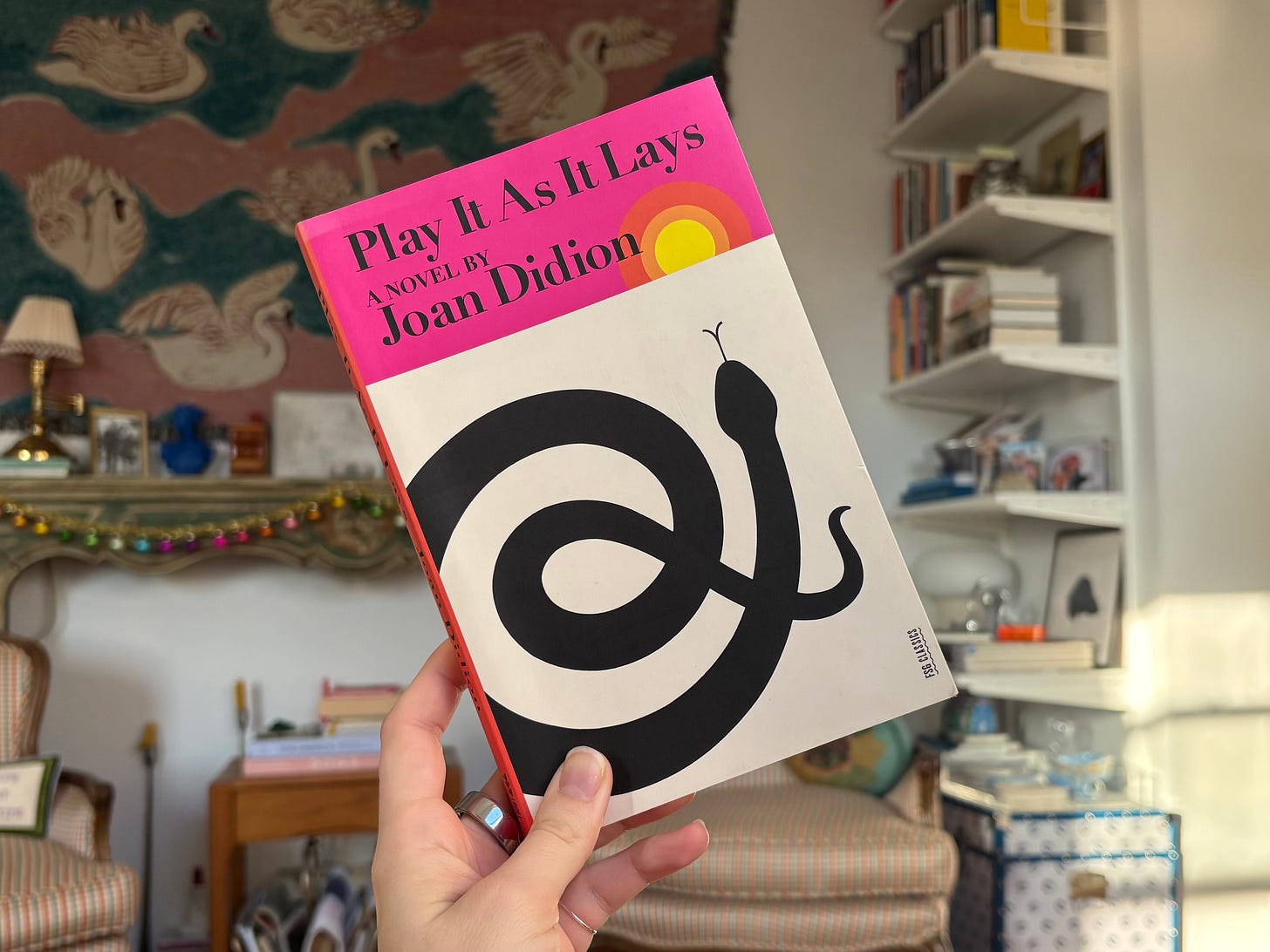

When I was reading Hemingway, I remembered that Joan Didion claimed she learned to write by copying down his sentences. I own two books by Joan that I haven’t read, so I picked up Play It As It Lays. It was something of a lucky selection because it seems to owe a lot to The Sun Also Rises (probably particularly when you read them one after another).

Namely, nothing happens in Play It As It Lays, and the characters are lost—less so aimless, more so stuck in a pervasive meaninglessness. Maria (pronounced Mariah, which I simply could not get through my head) descends into madness. She goes places, mostly nowhere in particular, in her car. She drives aimlessly around Los Angeles and out into the desert and dissociates. She also drinks and takes drugs to dull the pain of the fact that her daughter Kate lives in a care facility after some kind of terrible accident—it’s never explained. All the people around her work in or adjacent to Hollywood (including herself), and they’re all awful—alternately numbed or tweaked up on their own pharmaceutical cocktails.

Like Hemingway, Didion is spare with her language. She makes do with very little, but her result is much more hollow. I don’t mean that as an indictment of her skill as a writer because I think it’s meant to be hollow, but it’s hollow nonetheless. Didion achieves, masterfully, a novel with no grace, no dance. There is no connection between the reader and Maria, there is no connection between anything.

Praise for Play It As It Lays lauds Didion’s “mordant lucidity” and calls the novel “scathing.” I can’t argue. Didion is sharp; she is caustic. But if she is eviscerating the lifestyle (prevailing attitudes, society at large) that she portrays, attempting to tear it down, etc., well, she doesn’t offer MUCH in the way of something to fill the void she leaves. I enjoyed the novel while I was reading it, but in the weeks since, I haven’t really thought of it. It’s not thought provoking, it just is.

Worth noting perhaps that people in LA apparently love this book, so maybe there’s something specific to place in it (à la Hemingway too!) that missed me.

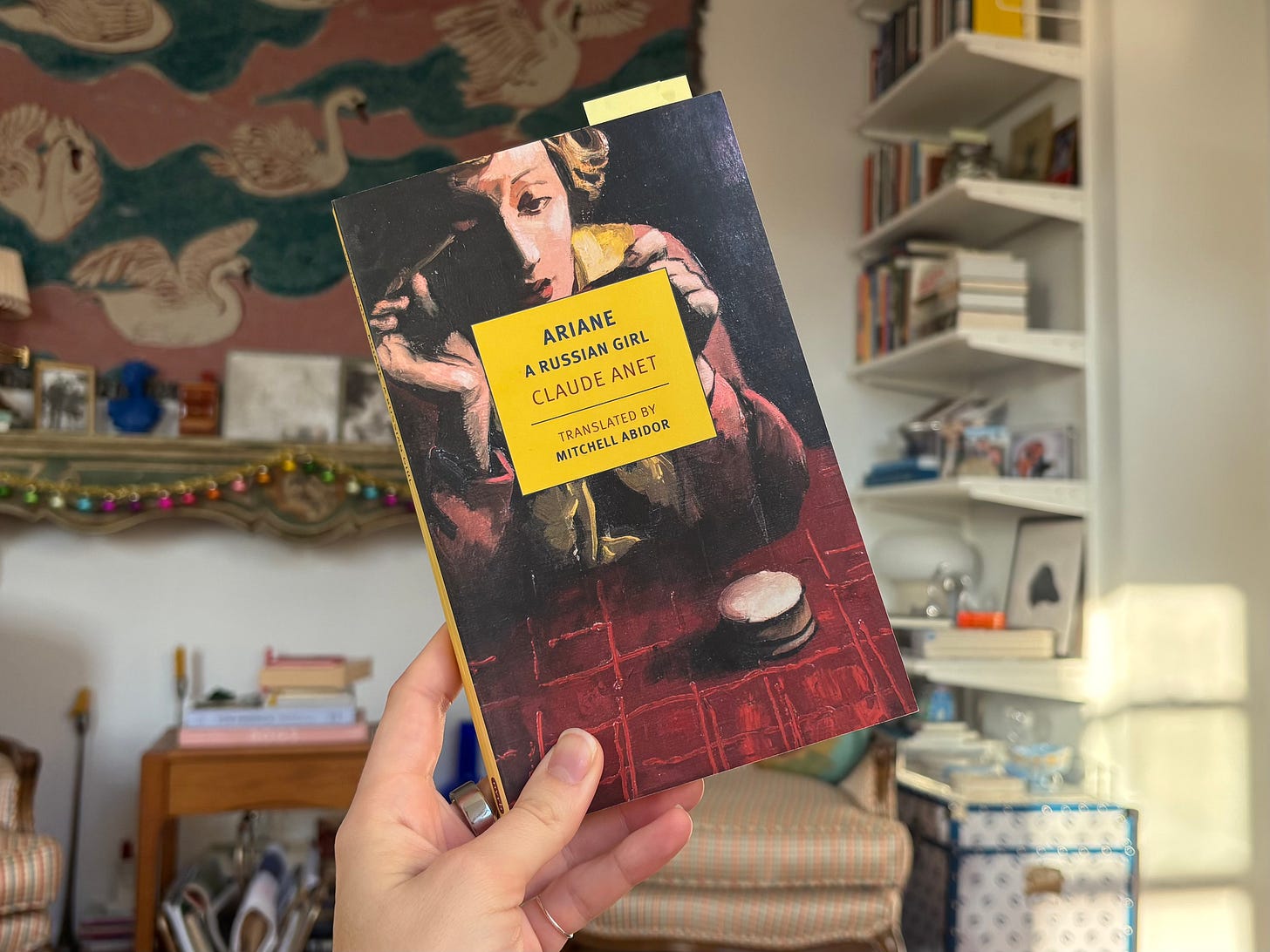

At this point, I was ready for something with a bit more hmmm…plot, maybe even a bit of romance, but I also needed it to be kind of dark still so as not to shock me out of the stupor Hemingway & Didion had put me in. Ariane A Russian Girl by Claude Anet had been sitting on my shelf for many moons after it was purchased online during an NYRB fall sale, only to be forgotten/forsaken. The back describes Ariane as “the queen bee of her provincial Russian town…tired of breaking hearts in the sticks,” and promises “a brilliant exploration—engrossing, unnerving, comic, and cunning—of the matchless cruelty of desire.” Sounds good!

And it was—good and insane. Set in a pre-revolutionary Russia, where old-world propriety shows signs of falling to a more promiscuous way of life, our Ariane is very modern indeed. Her natural facilities are supplemented by the tutelage of her equally modern Aunt, who doesn’t believe in love, and doesn’t believe in constraining her charge either. With her sweet good looks, cunning intelligence, and hint of wickedness, Ariane is completely magnetic. Even as we are told that she has that “mix of haughtiness and mockery that, truth be told, caused her to be hated,” we are trapped in her web along with every single man she meets.

It’s not long before the little one has figured out how to manipulate everyone around her to get just what she wants. But what does she actually want? To go to Moscow and to be free. Well, naturally she makes it to Moscow, but there she meets Constantin Michel, a man too many years her senior for it to be romantic, even without the rampant manipulation that plagues their relationship from both quarters. Neither is willing to give up the upper hand they imagine they have, and so they punish each other. Everything changes.

I won’t claim that the romance I was looking for is what I got. Ariane is a fairly disturbing portrait of love, particularly by our evolved standards, but also a highly entertaining one. The characters, and the subtlety with which Anet renders their motivations—allowing them to believe in their own delusions, refusing to give them away to the reader—is really very well done. In the end, love is the great equalizer.

While Ariane was more lively than Hemingway and Didion, and was more of a story in the traditional sense, my hunt for plot continued. I thought it might be good to sink my teeth into something a bit meatier. My eye was drawn to The Little Friend—the only Donna Tartt novel (of her 3) that I had not yet read. This book would have sat on my shelf forever. Though I’ve owned it for a while, and known about its existence for much longer, I have never been drawn to pick it up. Plus compared to all the (continuing, commercial, critical, etc.) buzz around Tartt’s other novels, The Little Friend doesn’t get much action, which makes you wonder…

The novel is set in small town Mississippi over the course of a single summer in the 1970s and focuses on the Cleves, and in particular the youngest of the bunch—Harriet, who is twelve years old. One of the first things we learn about the Cleves is that they love to talk about the past, “loved to recount among themselves even the minor events of their family history—repeating word for word, with stylized narrative and rhetorical interruptions, entire deathbed scenes, or marriage proposals that had occurred a hundred years before.”

This habit is part myth-making, part trauma processing: they go over the past in large part to translate the horrible events of thier share history into “that sweet old family vernacular, which smoothed even the bitterest mysteries into comfortable, comprehensible form.” This includes all kinds of calamities, from the death(s) of husband(s) to the loss of the family’s beloved plantation home, Tribulation. One event, however remains too awful to speak of. Back when Harriet was just a baby, her older brother Robin—himself twelve at the time—was found dead, hanging from a tree in his family’s backyard on Mother’s Day. The police never found the person responsible.

The other family who comes more into focus in the second half of the book is the Ratliff clan. The Ratliffs are from the wrong side of town and are regularly engaged in criminal activity (ranging from petty theft to drug trafficking to capital murder). Danny Ratliff is one of five or six brothers, two of whom are currently in prison—they’ve all done their turns. Robin was Danny’s age, and when Harriet hears that people saw him hanging around on the afternoon of Robin’s accident, she is sure that he’s the one responsible. Her certainty is in no way impacted by the fact that Danny was cleared by the police at the time of the crime. She launches her own investigation with the help of her sidekick, Hely.

What follows is an incredible portrait of a bright and uncompromising girl trying to balance her (highly developed) sense of what is right with the realities of her world. It’s not just the injustice of her brother’s unsolved murder that she’s suddenly interested in, but also the racial and socioeconomic dynamics (in post-segregation rural Mississippi) that have been humming in the background of her life until now. In the course of a summer, much of the background of her life suddenly jumps into the foreground. The reader has a front row seat as Harriet takes her first (large) steps out of childish country where the world is made up of amorphous, seemingly unlinked acts and facts, into an unfamiliar territory where actions have consequences, and what you do becomes who you are.

Donna Tartt is a master storyteller, and The Little Friend is the type of novel that makes you think literally how on earth did she do that. Seriously—how did she do that? The pacing can feel slow at times, the details gratuitous, but somehow even when it drags, it drags you along with it. I think it’s probably Tartt’s least popular book in part because of the pacing and related genre confusion (a murder mystery with pages dedicated to how twelve year old girl occupies herself in a quiet house when she can’t sleep?). But if you let Tartt take you where she wants to take you, it’s an incredibly rewarding read. 10/10, favorite book of the month. LOTS of snakes though, so be prepared for that.

This was so fun to read, Eve !!! I love that your physical-tbr project is going well so far, and I loved the connective tissue you've included between each book, the process of deciding which one would be next. I'm looking forward to more! The Little Friend is also the only Donna Tartt novel I haven't read yet, and it's also been sitting on my shelf forever. Thinking I may take on a no-new-books project like yours after I wrap up grad school this spring (no more long syllabi of required books every semester!)

🔥🔥🔥🔥🔥🔥🔥🔥🔥🔥🔥