Happy New Year, dear reader! I mean that like a stranger on the street at 12:17am, not like a coworker asking you for a favor at 8:37am. I’m smiling, and my cheeks are cold and rosy from the January air. I mean it in the good way.

For the past month or so, I’ve been reading a masterpiece, and I sit down this evening, after a couple weeks of not writing feeling like it’s possible I’ve forgotten how to do it? Certainly feeling like my capacities are not strong enough to talk about this novel that’s so much more than a novel. How do I usually start these?

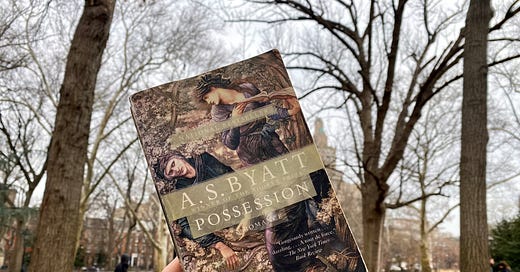

Possession by A.S. Byatt was published in 1990 and won the Booker Prize that same year. It was (is, because I think you get to hold on to that title) a best-seller, beloved by the public and critics alike. It is a romance, a detective novel, a poem, many poems, a letter, many letters, a criticism, a comedy, a tragedy, a fantasy, a, a, a. It is impossible to read it and not come away with a profound admiration for the author who writes across minds and centuries so seamlessly. I read it once before, years ago, and decided to do so again after A.S. Byatt passed away in November of last year.

In 1986, Roland Mitchell is examining an old book in the London Library in relation to his studies of (fictional) Victorian poet Randolph Henry Ash. When he opens the pages of this dust darkened tome, he discovers two letters to an unidentified lady, unsigned but written in Ash’s hand. All that is sure is that the lady is not Ash’s wife. Thus begins a hunt—a race to the end of a story that will upturn Roland’s monotonous and unsatisfying life.

Or I suppose it’s not really fair or right to say that the race begins there. Things don’t actually pick up until he discovers obscure feminist icon, poetess Christabel LaMotte—and the fact that she and Ash were documented meeting at the very breakfast mentioned in Ash’s draft letters. Who is the scholarly expert on LaMotte, or at least one of two and the closest one geographically? None other than one Maud Bailey at Lincoln University, not far from London.

It is there—when Roland arrives there, that the air becomes charged, and the gears start to turn at a more rapid pace. As the connection between Ash and LaMotte is uncovered by Roland and Maud, the tie that bonds the two modern day scholars, unspoken as it is, becomes more intense. They experience a protectiveness of it all, the correspondence and whatever it is that’s growing between them, which leads to secrecy, which leads to…yes, a sense of possession in all the various meanings of the word.

You see, aside from Maud and Roland’s sparking romantic something or other, and aside from the contagious curiosity about Ash and LaMotte, the plot is also driven by the other scholars (nefarious and not) who are on the trail of this momentous discovery as well. It is these other academics that put Roland and Maud on a precarious ledge and on a clock—threatening their feelings of fierce protectiveness (somewhat unexplainable even to themselves) over the story they are uncovering.

It really is difficult to capture the sheer breadth of what Byatt does here, what she creates. I know I said it, but it merits mentioning again. Possession is a deeply literary novel both in the actual writing and in the themes, but it is not overly erudite. It has real motion and real plot, heroes and villains, intrigue, clues and misdirections, love and sex and a happy ending (I think). It sits in a space that is very difficult to occupy successfully, somewhere between the high-brow and the common. Byatt manages the feat.

Which is not even to mention the poetry. The poetry! Our Victorian poets are not real historical figures you see, which means their poetry does not exist. But Byatt makes it exist. She writes it for both of them! It’s truly a mind boggling feat, and even more so since much of it is in metered verse. Which is not even to mention the letters! She writes like a Victorian. Sorry—she writes as two different Victorians speaking to each other and you can absolutely tell the difference. Which is not even to mention…I could have written this whole review using only sentences starting with that phrase.

Echoing the stylistic breadth is a staggering thematic breadth. The roles of the sexes, romantic power dynamics, societal expectations, questions of religion, the presence of supernatural forces, the right to privacy, the lack thereof, the purpose of art, the responsibility of art—all of this and more, in 1860 and 1980 and now, for me, in 2024. The study of history (literary or not) does allow us to study ourselves, doesn’t it?

One theme that struck me particularly was related to the ownership of art, in this case, of the written word. In Possession, Roland and Maud read Ash and LaMotte’s private letters, and feel ownership—not so much in a material way, but in the same way that I read this book and now feel that the experience of it belongs to me. It is a baffling effect—how the words manage to do this.

Maud and Roland have a right to these emotions and so do I, but I’m talking about a published novel. What right do they have to read what they read in the first place? When does scholarly curiosity and a desire to preserve the legacy of the supremely talented writers of the past become something else? When does it become a gross intrusion? Do great and talented men and great women forfeit their right to all privacy? Should they know to burn their private letters? If they don’t, does it mean that they harbor some secret hope that someone might find them 200 years later?

The advent of ~technology~ and data collection and AI (ugh) certainly doesn’t simplify these questions for modern artists and writers. I fear there is nothing to go on besides the pits in our own stomachs. Does it feel right, or does it feel wrong? Of course, all of our pits are different. Byatt doesn’t give us a concrete answer one way or the other. Her conclusion—the final and most private discovery (trying not to give too much away)—feels like a rape and an intended destiny at the same time.

In a surprise to no one, the other theme that struck me most, and one that is present in parallel between Ash and LaMotte and Roland and Maud centuries apart, is the question of surrender in love. Or otherwise put (yes, I’m going to do it again), possession in love. What we give up to each other and what we take. Here, Byatt most certainly does come down on one side. Painful as it can be—both in the moment and after the fact—to not surrender, to not possess, to not give and not take, is to live without the greatest pleasure. The greatest happiness. Picking safety over risk in the realm of love cannot be worth it.

Please do get in touch if you’ve read any of Byatt’s other books or stories or essays. She was so prolific.

Kisses from me to you!

This makes me even more excited to read Possession!! I have a weakness for books set pre-cell phone lol

Can’t wait to read this one!!!!!!