Nineteenth Century Ozempic

Try a Seance! One or Two by H.D. Everett

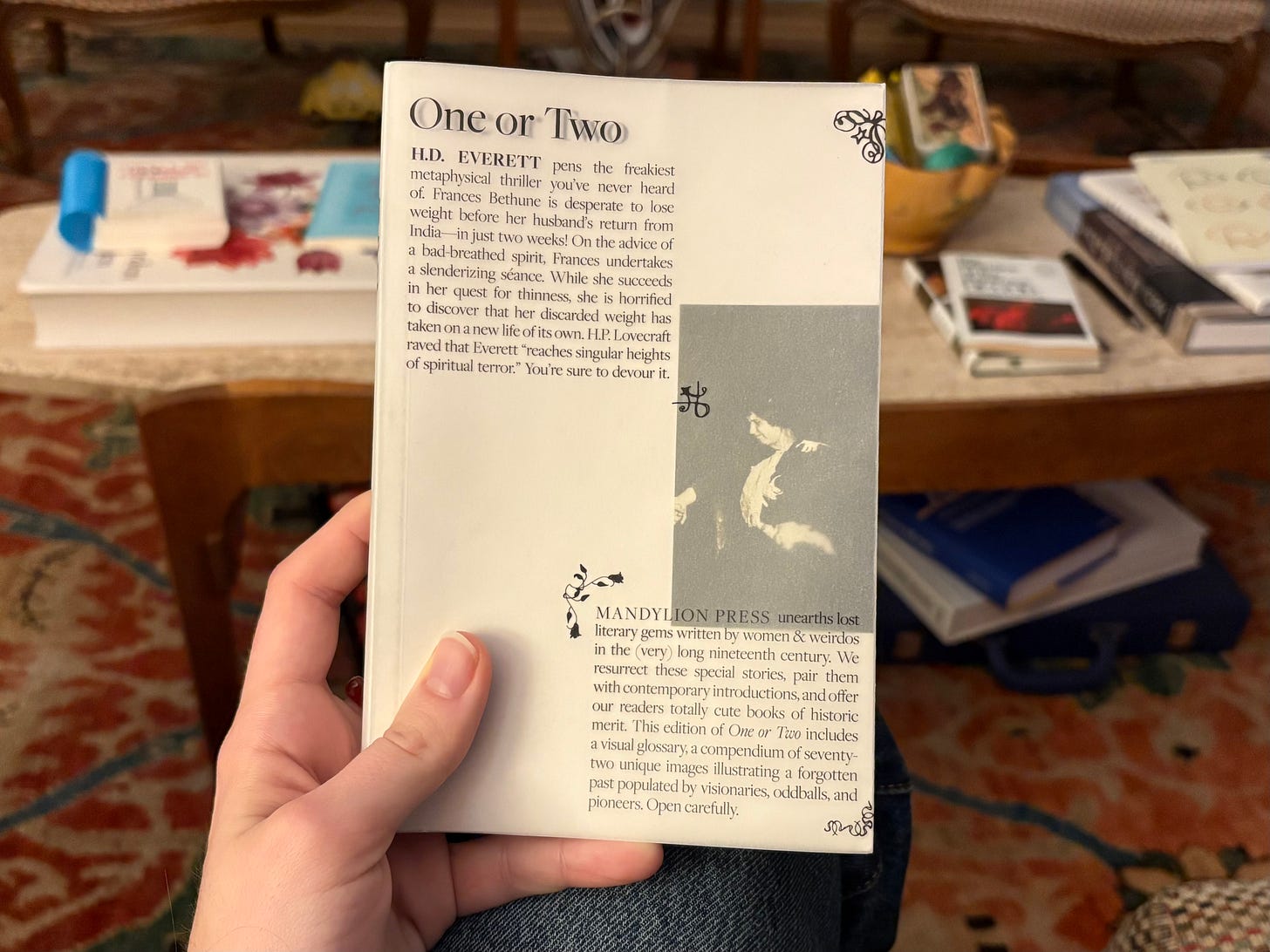

Last month, I had the distincttttt pleasure of reading One or Two by H.D. Everett, as republished by Mandylion Press. I’ve written about Mandylion Press before, but for those unfamiliar (i.e. new here or not paying attention), Mandylion (co-founded by Madeline Porsella and Mabel Taylor in 2022) uncovers ‘lost’ nineteenth century novels and publishes them with introductions that help to contextualize the stories and generally make you a smarter, more interesting person.

So far, Mandylion has published four books, most recently One or Two by H.D. Everett and The Morgesons by Elizabeth Stoddard. I am the proud owner of both, and though I was initially drawn to The Morgesons because:

“Cassandra and Veronica Morgeson are wild girls. Adored by men, hated by women and feared by their parents―they break the mold. Veronica refuses to leave the family hearth or look at the ocean. Cassandra travels from one house to another around Massachusetts, breaking hearts and sending men to their deaths wherever she goes.”

I ended up reading One or Two first so that I could go to book club at McNally Jackson (which was on Monday and was a DELIGHT).

One or Two is the story of a woman named Frances Bethune. About ten years ago, at a pure and beautiful eighteen years of age, Frances’s father allowed her to marry Charles Bethune because being without him made her physically ill. Shortly after the love birds were married, they set off to India for Charles’s military assignment there. After Frances falls off her horse and hits her head, but also after some mildly unsavory behavior on her part (read extramarital flirtation), it is determined that she had better go back to England while Charles stays in India for the remaining three or four years of his assignment.

That Frances is able to bear the thought of being apart from Charles for that long is the first indication of a change within her. The woman who returns to England is not the same woman who left, and this shift is made manifest by the fact that upon her return, Frances gets rather fat rather quickly. When she receives a letter informing her that Charles is en route home to England following a harrowing bought of Cholera, she’s catatonic. He doesn’t know that she’s fat, and so the fat must be got rid of!

With only two-ish weeks to halve her bodyweight, Frances turns to her old friend Ursula. The pair reconnected at a seance shortly after Frances’s return from India, and it’s off to that same medium that Frances sends Ursula when it occurs to her that a supernatural fix might be just the ticket. Much to Ursula’s chagrin, the medium does have a suggestion.

In order to halve Frances’s weight, all the women have to do is sit in a particular room at Frances’s home, with a curtain drawn between them. Ursula must stand guard and ensure that no one intrudes. Frances will go into a trance and Ursula must wait outside the curtain—even if it takes the entire night—for Frances to come out to her. It may take up to seven nights, maybe fewer, but if the weight does not…depart…after the seventh night, it will have been a failure.

This miracle prescription comes with an ominous warning though:

“Let her think well before she undertakes the trial, for once done there can be no undoing. Once withdrawn, the substance taken from her cannot be put back, not in life and not in death, any more than can a child when born from the womb. If inert matter only is separated, all will be well, but it is possible, tell her it is possible, that life may be divided out of life. Let her look to it that she is at one in her soul, with strength to put from her the evil and hold the good. Then the body will be strong likewise, to repel its grossness and emerge as one newborn.”

No spoilers!!!!! But after the fourth night, the morning comes, and well…life may or may not have been divided out of life. Frances is half the size she was the night before, but the other half of her…may or may not have separated itself into a sentient being that looks exactly like Frances did at the age of eighteen when she was adoringly known as Fancy. Madness and mayhem ensue.

On a fundamental level, I think that the novel is interpreting pressure that women face to be thin, young, beautiful, etc. and literalizing it. How could it not be? And Everett’s handling of the theme is eerily familiar. Certainly, scrutiny of the female form has not decreased since the nineteenth century. But beyond this, I actually think that Everett is using Frances’s weight gain and subsequent fixation on losing weight to demonstrate a larger idea. Simply put, overemphasis on the material world corrupts the human spirit.

We can see this transformation taking place in Frances at various stages through Ursula’s eyes. On the way back from the medium, Ursula wonders whether it is too late for Frances to again become the girl that Charles Bethune fell in love with. Frances thinks she can reverse time through physical change alone—she is hyper-fixated on her own material form—but her transformation began before she started gaining weight. According to Ursula and, later, according to Charles as well, it began in India. She learned to live off of external validation based largely on her physical appearance. She became worldly and vain.

Upon arriving back in London, ripped from her admirers, she becomes indolent and eventually, fat. Here again, we see her fixated on the physical. She cannot stand that she is no longer thin and beautiful, and the reason she can’t stand it is because it robs her of the attention she was so enjoying. When she goes to the supernatural extremes to get her figure back, she once again places the physical above the spiritual, so it follows that her spiritual corruption—well underway by now—advances.

After the transformation, Ursula is confronted by Frances’s garishly selfish attitude and wonders: “had the pure soul separated itself and taken shape, leaving the original form wholly to the evil?” And for my money, the novel’s answer is yes.

It makes me wonder what’s in store for us as a society that places increasing value on physical appearance. In her intro, among other fascinating tidbits about seances and souls and scientific advancement, Madeline quotes a photographer Oliver Wendell Holmes who, in the middle of the nineteenth century, pronounced that “form is henceforth divided from matter”—form being the essence of something and matter being the physicality.

Form was divided from matter, and matter lost the significance it once had. Do you need to go to the beach when you can hang a photo of it on your wall? Now almost 200 years later, even form seems to be increasingly irrelevant. The essence or meaning of something is secondary to what it looks like, what it seems like. Does the beach mean anything at all beyond providing a backdrop or showing people you were there? Forget about the beach though. Do you need to be a moral, substantive person or do you just need to look good?

One need not spend more than forty-five seconds scrolling on Instagram or TikTok before being force-fed content (there’s something in the hollowness of the term “content” that’s in conversation with the form/matter divide) that’s purpose is to make you feel like you need to change (improve) your physical appearance.The beauty / self-care industrial complex markets this fixation on appearance as the key to inner peace and harmony.

Having read One or Two (which you should read too by the way), I can’t help but feel that we’re being sold a lie. When Frances gets skinny, she starts to look old. In the novel, it’s because half her life force just fled to a new body and the remaining baseness of her spirit is kind of collapsing in on itself. But in real life, just ask the plastic surgeons who are fixing people’s faces after Ozempic hollows them out. Time for the rouge. Time for the filler. There is always, will always be, some next thing. When you tie your happiness to the material—including to your own material—that happiness cannot last.