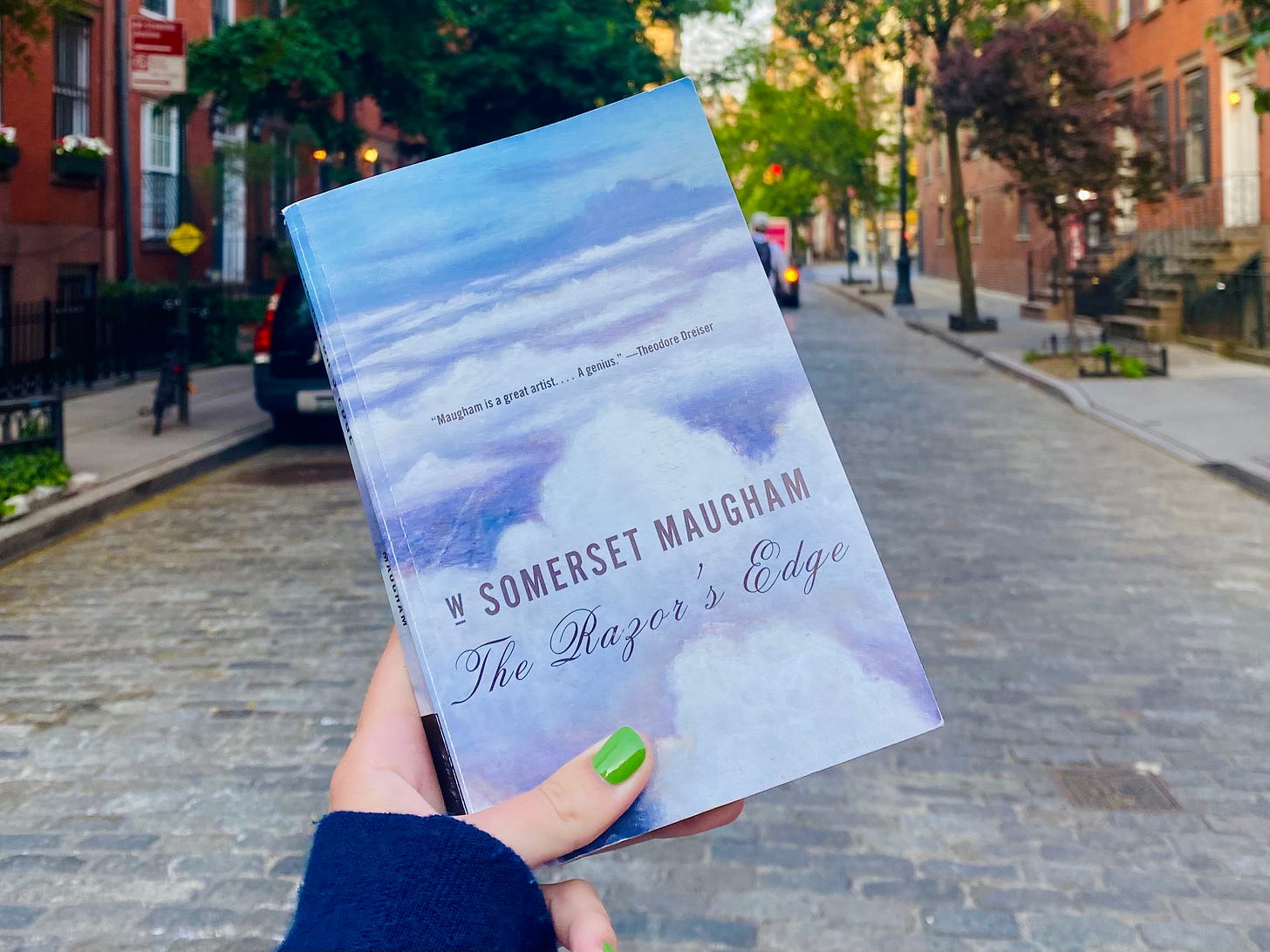

On The Razor's Edge (Literally and Figuratively)

This week’s book was another winner, and I wrote more than I meant to (as per usual), so I’m going to dive right in: The Razor’s Edge by W. Somerset Maugham is narrated by the man himself since he writes himself in as a minor character. From this vantage point, he tells the story of three main characters: Elliott Templeton, Isabel Bradley (later Maturin) and Larry Darrell. The events begin in 1919 and end right around the beginning of World War II. All the characters (with the exception of our narrator and a few other minor players) are American, but the majority of the novel I set in Europe, namely France. I think that’s pretty much all you need to know for now. I was feeling a little slumpish last week, hence the hiatus, but I’m feeling re-energized this week, so I’m ready to go. I’m also excited to write this post because this book brings to life some of the things that I’ve been turning over in my head of late…some of the things that were making me feel slumpish. Let’s get into it.

To begin with our author, whose style I quite enjoyed but who I had never heard of before, W. Somerset Maugham was a playwright, novelist and short story writer in the first half of the 20th century. He was apparently wildly popular during that time, and according to Wikipedia (sorry but I didn’t have time to read this novel and also a biography before writing this post), he was the highest paid author during the 1930’s. Either I somehow missed the memo on this one, or people don’t talk about Maugham as much as they should? I don’t know but novels like this are the reason I rarely read contemporary literature - there’s so much to get through from before I was born. Maybe 50 years from now I’ll finally get around to Hello Beautiful World, Where Are You. Also Maugham was a spy for the British Secret Intelligence Service during World War I, which is cool as shit.

Now to the meat of it, as I briefly mentioned, The Razor’s Edge is framed as a true story - in the opening chapter, Maugham directly addresses his reader, saying that the only reason he’s calling the tale that follows a novel, is because he’s not sure what else to call it. It doesn’t end in death or marriage, but rather, “leave[s the] reader in the air.” (3). Furthermore, he admits that he only spent time with his main character (Larry, although in my opinion Larry is no more “main” than Elliott or Isabel) infrequently, and that he knows very little about what occurred in the gaps in time between their meetings. It is a very intriguing way to begin a book.

I suppose it is possible that this first chapter is not just a device to set up the premise of the book - it is possible that Maugham really wrote this book about people he knew and spent time with, changing only the names. I haven’t found anything anywhere to suggest that the story is in fact true, so I will treat it as a novel, beginning with an ingenious device - a device that creates sense of simultaneous proximity and distance, and allows for the reader to be present for some of the important action of the novel, while hearing about the rest of it second hand.

The other effect of this framing device is that Maugham, as narrator, is able to pass judgement on our characters and their actions without being judgmental. It is extremely well executed, and for me, this set up made the characters the best part of the novel. They are so good precisely because they are described by a man who claims to be detached from the drama of their lives but in reality is not - at least not always. They are real complex human beings, while also being caricatures of themselves. That is where the simultaneous proximity and distance most comes into play.

I will start with Elliott Templeton because he is my favorite, described by Maugham as a snob, but to me a kind-hearted social climber. An expatriate living in Paris, he is in his late fifties at the beginning of the novel and “society” is his life. In a way, he is supremely superficial, but upon closer inspection, he is simply a man in the second act of his life trying desperately to hold onto a way of life that is becoming increasingly irrelevant. He operates with kindness and generosity within the governing laws of his own little world. All of this comes through so powerfully because Maugham treats Elliott, more than any other characters, with a degree of tenderness. Even through the jokes and the pokes, it is clear that Maugham as our narrator is genuinely fond of Elliott, and so too am I. I realize now, since I forewent a plot summary, I should also mention the fact that Elliot is Isabel’s uncle.

Which brings us on around to Isabel and Larry, who I will write about together because they are each other’s shadows - they define each other’s contours, and at the beginning of the novel they are engaged. I don’t consider it a spoiler to let you know that they don’t get married because that’s really not the point of the novel and also their split happens fairly early on. I could go on and on about these two, but I will try to keep it short (famous last words). They are both childish and stubborn, although not unlikable. Isabel is material and Larry is spiritual, and for that reason I like him a little bit better than her, but as my father always told me, not liking someone only means that you see something in them that you might not like about yourself.

I realize that I’m being sort of vague, and so to hone in on it a bit I’ll say this: Larry comes back from World War I and something has changed. He doesn’t fit into Isabel’s world anymore - the American dream, manifest destiny world - in which all the money in the world, hell, all the world, can be yours if you just put your nose to the grindstone. She wants him to get a job and make some money so that they can get married, and go out, and throw dinner parties, and be seen at the right places and the right clubs. He wants to loaf - or so he says - but really he wants to read and learn and, to put it most simply, find God. Needless to say, they must go their separate ways. The conversation that they have when they do go their separate ways is one of my favorite literary conversations that I’ve ever read. I can’t do it justice, and I can’t even really put my finger on it, but it feels like a simplified version of the most important conversation of all time.

It’s a conversation that plays out in my head not infrequently, almost like the angel and devil on my shoulder, but it’s Larry and Isabel. One says, “go lead a life of knowledge, a life of the spirit - untether yourself, and at least try to find out what life is about” and the other says, “stay and live it up - go out to all the parties with all the right people, and buy all the nice things that you want to buy. This of course requires money, so you must work, but that’s just what you have to do.” The second voice sounds superficial, much like Isabel seems superficial in this novel, but it is not, and she is not. Humans are social animals, and although a spiritual path like Larry’s does not exclude friendships and socialization, it shrinks those things down to an infinitesimal external piece of a massive and massively internal life. It’s not wrong to want to have strong bonds with others or to want to have fun.

The piece that I suppose I’m trying to get at is the fact that in The Razor’s Edge Larry and Isabel make their choices, and there is no middle ground. Larry says, “I wish I could make you see how exciting the life of the spirit is and how rich in experience. It’s illimitable. It’s such a happy life,” (73). And Isabel responds: “I’m just an ordinary, normal girl. I’m twenty, in ten years I shall be old, I want to have a good time while I have the chance” (74). Larry’s claims are so enticing, and sometimes I feel that if I could spend all of my time loafing and reading and learning, I would be the happiest version of myself. But then I remember that I am just an ordinary, normal girl who wants to have fun. And as much as I love to read and learn, the people in my life are more important to me than the people I read and learn about. And so, I’m left wondering…is it possible not to choose? To have both, to have it all?

I feel that the answer must be yes - at least in some capacity. I think in this case, half of each is better than all of one, particularly when I acknowledge that there’s something to be learned about the meaning of human life by actually being a part of everyday human life (as opposed to a more solitary approach), but I feel that’s a conversation for another day. I’m getting sunk into this somewhat philosophical hole without even a rudimentary knowledge of philosophy, so I must dig myself out. I think it it possible to have both, but it all comes down to time. Much like Isabel, who thinks that by the age of thirty she’ll be old (silly then and ridiculous now), I sometimes have the feeling that time is passing me by. Or rather that there’s not enough time in the day. How am I supposed to read all the classics and learn to meditate and take care of my body, when I also want to go shopping and go out drinking on Saturday and take a vacation, and, and, and…

All of this somewhat personal rambling entirely leaves out the external pressures that the average person today deals with. When you scroll on social media every other person is touting the newest wellness trend to get your mind right and in between those are the girls telling you that this is your sign to book a one way ticket to Tulum with your 8 best friends. It’s exhausting. We now live in a world where we not only know what all of our friends are up to all the time, but also all of the fun things that near or perfect strangers are doing. And we don’t read about it in the society pages of the newspaper like they would have in the 1920’s - we watch it happening live. It puts an enormous amount of pressure on the Isabel parts of us. And in order to calm that little Isabel voice inside, I think we must get in touch with the part of us that is Larry. The part that is a little more detached from the external and in touch with the internal. I hope one day to be able to find the balance.

I realize at this point I’ve maybe talked (written) myself in circles. These concepts are big ones to think about, and it’s obviously difficult to come to a satisfying conclusion to these ruminations. Much like Maugham, I suppose I’ve left you a bit up in the air, and for that, I’m sorry. I’ll close by saying that this book was pleasant to read from start to finish - and despite my subsequent internal (and now external) debating, it was actually quite easy reading. Maugham provides plenty to think about, but he doesn’t make the reader work too hard. Thank you to my dear cousin Georgina Ohrstrom for sending me this book and setting me off thinking :)