Shorties Pt. 6

4 actually short books! under 100 pages each. each and every one about death (unplanned).

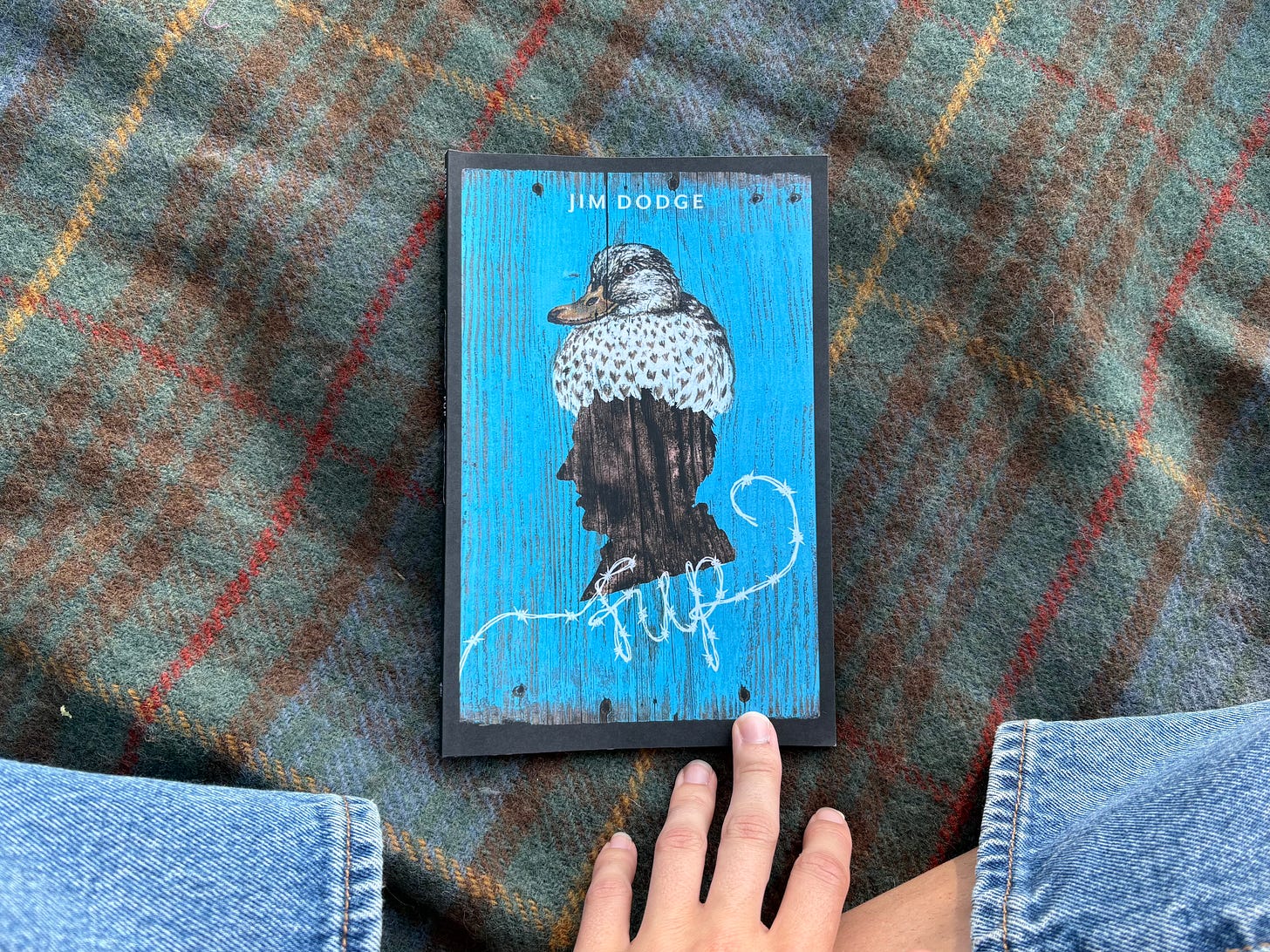

Fup by Jim Dodge

52 pages

Fup is a fantastic little tale about an orphaned boy, Tiny, the immortal grandfather who takes him in, Granddaddy Jake, and the giant duck they rescue and keep as a pet. The duck is Fup. Grandaddy loves his homemade moonshine whiskey and sitting still. Tiny loves building fences and is highly skilled in that field (ha ha). Fup loves food, that’s why she’s so big. She quacks for yes and hisses for no.

Also on the scene is Emma Gadderly, a social worker who menaces Grandaddy Jake about his Ol’ Death Whisper operation. She doesn’t understand that the elixir is what makes him immortal. Graddaddy, Tiny and Fup all drink at least a shot’s worth a day. The only other man to try Ol’ Death Whisper was Johnny Seven Moons, an Indian who Granddaddy befriended a while back. Granddaddy thinks that Seven Moons might be reincarnated as a particularly vicious and un-kill-able wild pig named Lockjaw. This is troubling to Grandaddy because Lockjaw is Tiny’s mortal enemy. Tiny is very focused on killing Lockjaw, and if Lockjaw is Seven Moons…well in that case, Grandaddy would prefer that Tiny not kill him (them?).

If you think all of that sounds a little wild, you don’t know the half of it. One suspects that Dodge’s central goal is not to elucidate, but rather remind his reader of just how much in life is beyond our understanding. Thusly, all that is incomprehensible in life is packed into this slim volume. Grandaddy understands this dynamic well (perhaps aided to acceptance by his Ol’ Death Whisper and its purported hallucinatory effects). He says, and is at peace, the most unimaginable peace, with the fact that “it just ain’t possible to explain some things, maybe most things.”

Tiny still struggles to come to terms with life’s mysteries. Only someone who hasn’t come to terms has a passion for building fences. And this worries Granddaddy too. He loves Tiny more than anything, maybe tied with Ol’ Death Whisper. In the end though, Tiny make some progress. He advances from fences to gates, and then from gates to hand-carved gate post ornaments. Art! This is good enough for Granddaddy.

Jim Dodge has a voice that delights. He writes his world and his character just as they are, avoids fluff at all costs, and despite his focus on the unknown, never deals in uncertainty. Even in a story full of unbelievable events (really truly, I’m talking magical & supernatural), he comes at it in such a matter of fact way and relates it so convincingly, you never blink an eye. It’s tragic, deeply loving, and even more tragic because it’s so loving. And it’s laugh out loud funny. I’m going to make my lover read it and then everyone else I know.

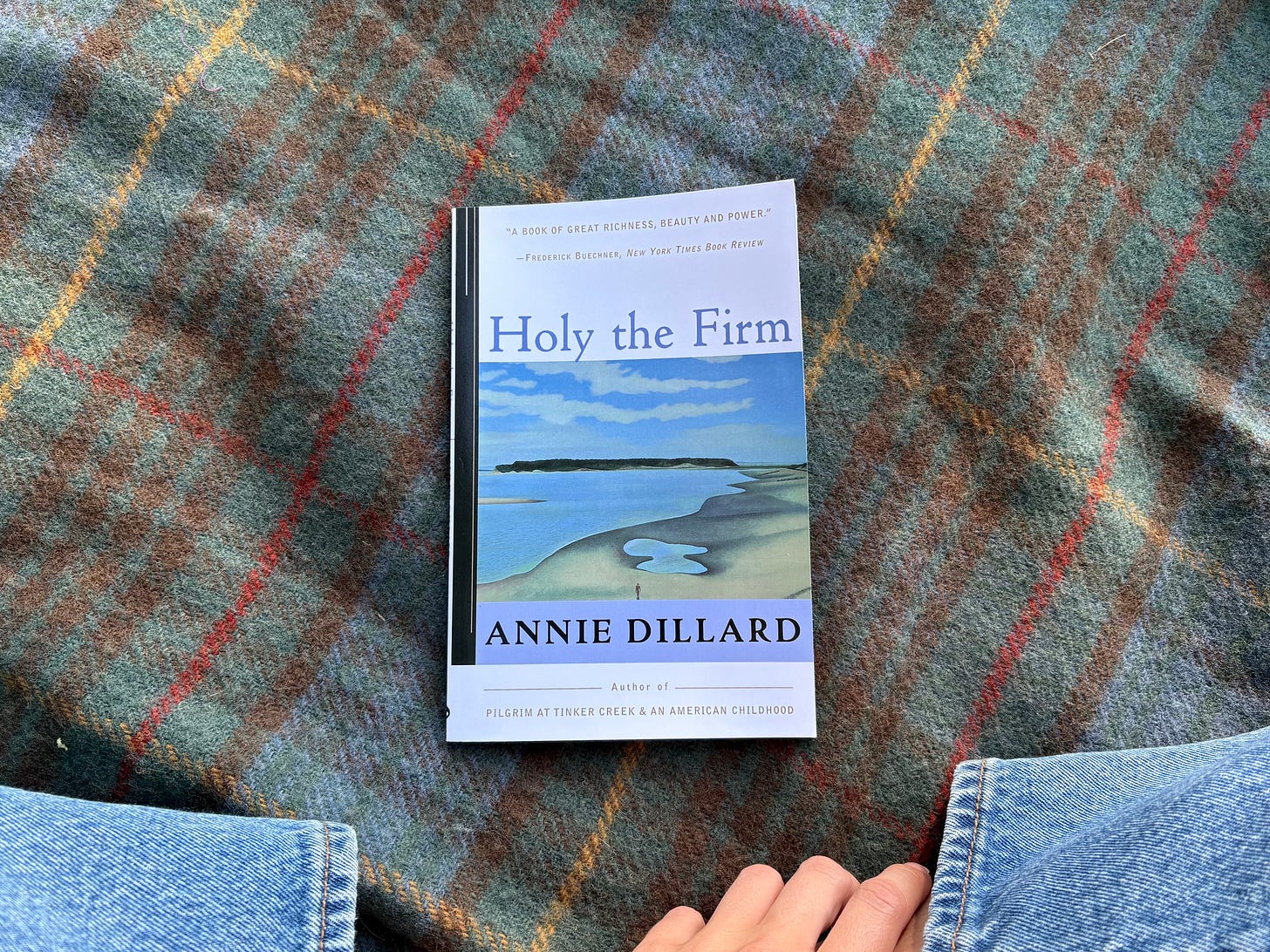

Holy the Firm by Annie Dillard

76 pages

Next up is another book that’s content punches well above the count (or should I say weight) of its pages. Though by now I should stop being surprised by these heavy little books. It seems a feature not a bug that they tackle the biggest questions. In Holy the Firm, Annie Dillard asks nothing less than the following: Who is God, and is this really what He wants?

The book—a journal of sorts—tells of Dillards time in Puget Sound. She’s decamped to an island there to learn to be a writer again. To learn to want to be a writer again. Early on, in describing her home there, and it’s inhabitants (her, her orange cat, a spider on a web in the corner of the bathroom behind the toilet), she describes the circus of a moth on the bathroom floor, below the web. The sight of it reminds her of a camping trip in Virginia. One night on the trip while she was reading by candlelight, a moth flew into the flame and was incinerated. The description of this event constitutes two pages of some of the most evocative descriptive writing I can call to mind (recency bias be damned), and that’s Dillard’s gift.

Not a few more pages on, The cat brings in a dead wren, and then a few minutes later, drags “a god scorched” onto the front porch. Dillard describes a “perfect, very small man,” with smoking organs hair and long folded wings and a hot walnut shell of a skull. She rescues this god from the cat of course and he flies away. It is at this point that the reader begins to understand the place that Dillard is attempting to bring them into—that dizzying space between the real and the imagined (spiritual, emotional, figurative).

The unreal images that she invokes though—the god scorched, or new islands rising out of the haze outside her window, or Christ himself being baptized in the bay—find purchase in a real world where something real and terrible has happened. There’s been a plane crash, and no one would have been hurt had the fuel tank not blown up as the father dragged his otherwise unharmed daughter, Julie, seven years old, away from the wreckage. But the fuel tank did explode, and Julie, struck by a burning projectile, has had her face burnt off.

The writing made me squirm. Made me anxious almost—which I realize sounds unpleasant, but it wasn’t. Dillard is searching and in writing her search down, she’s bringing you along. She, like any searcher hopes for, yearns for, some great discovery or resolution, and fears that it may never come, fears that if it comes it may be awful. In reading, you yearn and fear with her. She wrestles, and you wrestle. Perhaps the resolution is not great or awesome or awful. Perhaps it is simply this: it is good to search and fear and wrestle. As Dillard says, “‘Teach my thy ways, O Lord’ is, like all prayers a rash one, and one I cannot but recommend.”

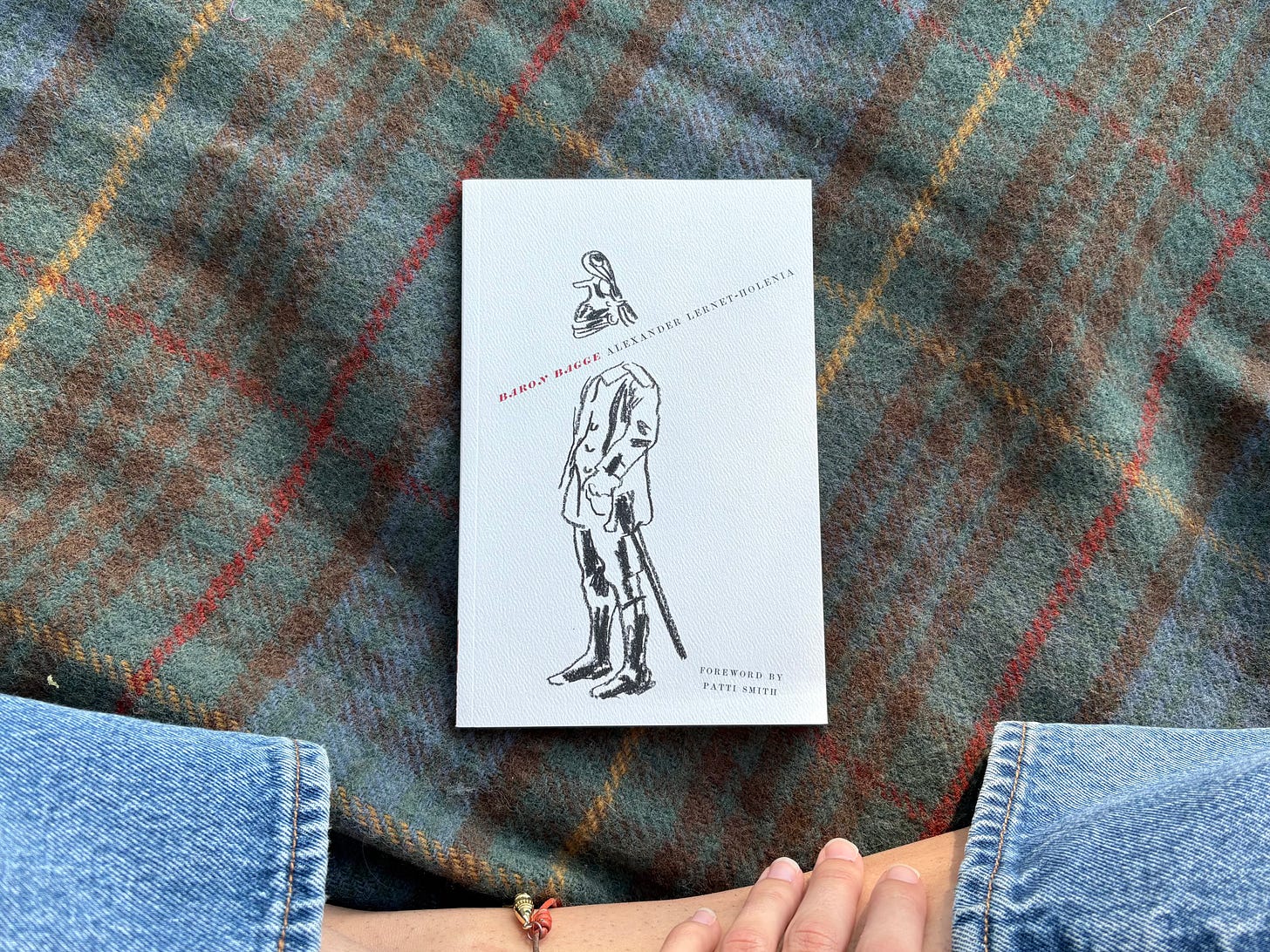

Baron Bagge by Alexander Lernet-Holenia

64 pages

In her forward to Baron Bagge, Patti Smith pretty much nails it right off the bat: “The clarity of love is an unassailable thing.” That’s what this little book is about, but one would be forgiven for getting swept up in the rest of the tale and…if not missing the point, then losing it for a bit. Alexander Lernet-Holenia—translated from the German by Richard and Clara Winston—does sweep you up.

It begins quite ordinarily. In a stage-direction-y, italicized setup, we are informed that the story to follow was related to a group of gentlemen by one Baron Bagge, in the aftermath of a narrowly avoided duel. We learn that Bagge fought in the war—the first war—and was stationed in the Hungarian Plain. In February of 1915, his captain led their division into a terrible slaughter. Only Bagge and two or three others survived.

This all we know by page five, so what is to come? Bagge tells us quite simply—the story that follows takes place, “in that time and space which intervene between dying and death itself. For that there is such n interval, many people consider quite certain.” Teased and intrigued, Bagge starts back at the beginning (before the slaughter). We are thrust out onto the snowy plain, under the command of an unstable and foolhardy captain. He leads us into certain ambush—the certain ambush that we think must be the slaughter we’ve already been told about—but then shockingly we prevail. Well, they prevail, we’re just reading along.

However, things get very strange in the aftermath of this unexpected victory. Bagge feels a “disquieting sensation of dreaminess,” almost like he’s been left behind. As his division rides on, his fellow lieutenants are acting very strange. Every moment feels sure to bring on another encounter with the Russians, but the enemy is nowhere to be seen. It’s all very eerie, but nothing could prepare Bagge for what he will encounter in the next town they ride into. It is full of people, enormous families, banquets, costume parties, general revelry. In this strange land, they live to excess and think of nothing but their own amusement. And there, waiting on the outskirts of town to welcome them, is the most beautiful woman Bagge has ever seen—Charlotte a goddess with eyes like the blue sea!

Lernet-Holenia’s writing is transportive. You really do feel like you’re there on the cold plain in the driving snow. You’r there in the warm living rooms, where there’s dancing before dinner. You feel Bagge’s unease. His confusion at this seemingly protected enclave, where the war is no concern. His amazement at Charlotte’s openness and her certainty. Their love story unfolds over this undercurrent of unease and amazement. Bagge suspends his disbelief so energetically that he ends up somehow on the other side of the coin. The dream becomes his truth, and reality merely a dream.

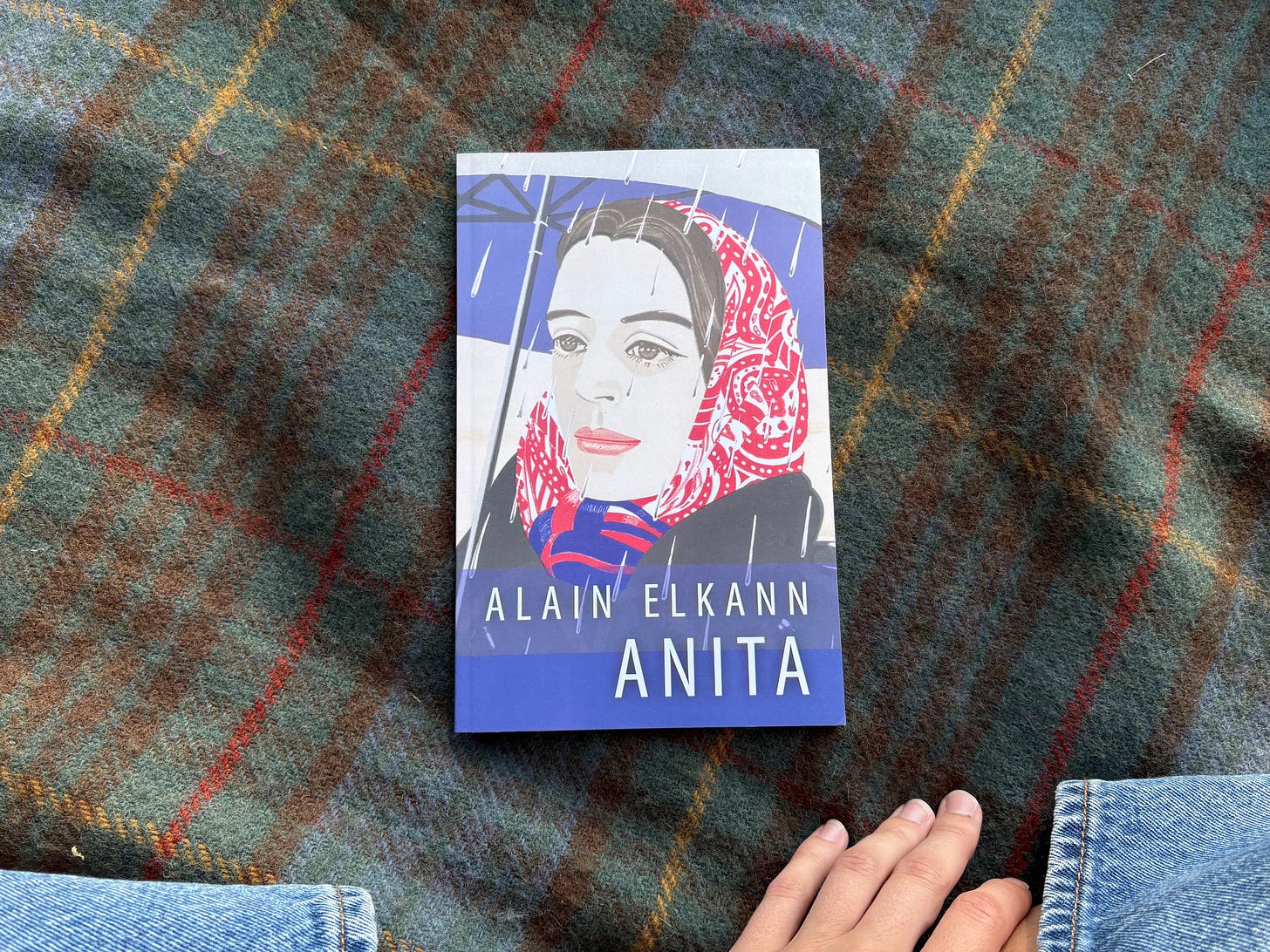

Anita by Alain Elkann

(73 pages)

I picked Anita up at Rizzoli, a favorite bookstore of mine that I rarely visit because I’m rarely in the area. Well, I was there, maybe in the spring, and I decided to play a game that I sometimes play, scanning the fiction shelves for the thinnest possible spines and picking out a stack of little books that I’ve never heard of and will be able to read in a day. Anita, with it’s compelling cover, see above, compelled me. The back, when I turned it over to see what it was about, contained only the following quote: “Would Anita and I remain together forever, as she said?”

So I, reasonably, I think, expected a fictional love story about a woman named Anita and whoever it was who loved her. Well, it’s not that. Not really. For one thing, it’s not fictional (this is a Rizzoli shelving issue more than anything else). In one chapter in the second half, in a meta moment, Elkann recounts a lunch with a friend where he shares that he’s working on “a thing,” a kind of meditation. Okay so it’s a meditation on love and his relationship with Anita, right? Well, yes kind of.

He spends the first twenty pages or so on this. On his relationship with Anita. Imagining their life together, had they met earlier on instead of in their middle age. Recounting the reality of their life together now. The friends and children that populate it. And then Anita’s mother dies, and another close friend as well.

From there, Elkann veers off into, what I would describe, as forty pages about the pros and cons of burial versus cremation. You see, he always planned to be buried with his father in Paris, but Anita wants to be cremated. On top of that when Elkann’s step-mother passes away, he discovers that his step sister now has control over the remaining burial plots. Of course, she will give him his plot, but it’s all very unexpected. It requires a consideration of death’s realities that Elkann has been wary of, but that he must now permit. Elkann’s father was Jewish and his mother, Catholic, so though he himself is not religious, his sense of tradition as informed by these influences plays a heavy role.

So—Anita is a love story, but it’s not just loving Anita, it’s loving life—what it means to be Alive—when faced with death. His findings are sprinkled in, not final revelations about the meaning of it all, but small moments of understanding and presence and joy. My personal favorite: “As long as one is alive, is there anything lovelier than gossiping with friends on a sunny morning in a cafe, over a cappuccino with brioche, or a Campari soda with toast?”

that Dillard review!!!!!! I'm always wanting to read more of her and now I really must!

What a delightful collection of reviews. I am currently in a big book phase, so maybe these would serve as good palate cleansers in between.