The Son Always Sets

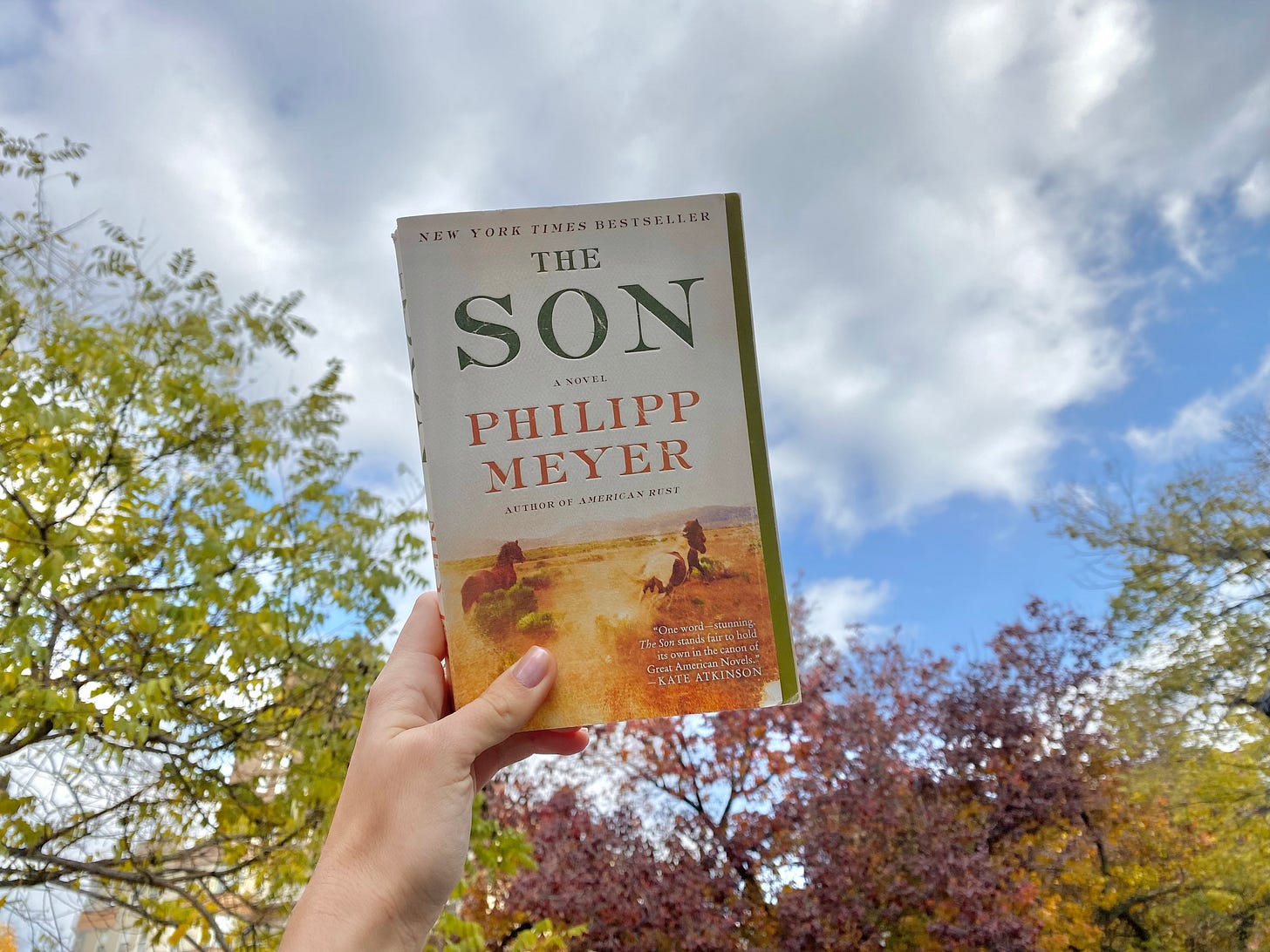

Happy May, dear readers! I am unseasonably ensconced by the fireplace at the Marlton Hotel, preparing to give you all the gift of knowledge. More specifically, knowledge of the masterpiece I just finished reading: The Son by Philipp Meyer. Not that I’m the first to discover this truly incredible novel (work of art) - I’m actually quite behind the curve on this one. For bringing me up to speed and setting me on the path of righteousness, I would like to thank my uncle, Murdoch Matheson. The second of Meyer’s novels, (following American Rust) The Son was met with critical acclaim upon its publication in 2013, and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2014 - recognition that is very well deserved. I loved this one from the first page to the last. Meyer deals in the profound and the disturbing in a way that doesn’t leave you feeling profoundly disturbed. It’s quite a feat, and I feel lucky to have read this book.

When I finished The Son late last night, I sighed contentedly, and contemplated my own mortality. After a few minutes of that (strong stuff), I became excited to write this post. This novel is a sweeping, generational epic, and I want to do it justice. It tells the story of the McCullough family, starting with Eli, and spanning four generations of sons and one daughter. Meyer tells his story through three primary characters, Eli, his great granddaughter, Jeanne Anne, and his son, Peter, in alternating chapters in that order. As such, we hop back and forth in time, and pieces of one character’s story get picked up and weaved into those of the others in interesting ways. Although it is the story of one family, that is merely the vehicle through which Meyers examines the cyclical nature of power - the rise and fall of one family echoes the rise and fall of empires. Before I get ahead of myself, though, I will provide a basic outline of the plot. I’m really going to try to avoid spoilers because you must read this one, so bear with me.

In 1849 at the age of thirteen, Eli McCullough is abducted from his family’s Texas homestead by a raiding band of Comanches. His father is off chasing pony thieves, so they rape and murder his mother and sister and abduct him and his brother. Eli, renamed Tiehteti by his Comanche captors, is adopted by a Brave named Toshaway and lives as one of the tribe for the next three years of his life. Eli is “rescued” (I use that term very loosely) and returned to the whites at the age of 16, and makes friends with a judge in Austin, but struggles to adapt. He joins the Texas Rangers, then the Confederate Army, then settles down, as much as a man like him can settle down, into the life of a rancher.

Peter McCullough, Eli’s son, is an adult when we pick up the thread of his life in 1915. Peter is the oddball of the family. Uneasy living in the shadow of his now well-known father and wary of the increasingly outdated way of life that father embodies, Peter struggles with his legacy. He feels an acute sense of guilt for the actions of his forefather(s), but he is unable to leave the land. Although he has very little to do with it, Peter tells the the story of how the McCullough land is transformed from a cattle ranch into an oil producing machine.

Jeanne Anne (Jeannie or J.A.), who we meet for the first time upon the occasion of her death, inherits the land from her father (stupid and proud) in 1945, not because of any particular love between them, but because the McCullough men keep dying. Jeannie’s narrative does not run quite as chronologically as the others, and though Eli (know to her as the Colonel) was alive for the first decade or so of her life, her story feels a bit more removed. In addition to an extra generational gap, Meyer effectively captures the feeling that the speed of human time exponentially quickens. By the end of Jeannie’s life, there is, at least physically/corporeally, very little remaining that would be recognizable to Eli McCullough. Now I am getting ahead of myself - Jeannie inherits the land and turns the McCulloughs into a true Texas oil family. She does everything she can to ensure that the name, and the legacy, and the money will live on. At what cost and for who, I’ll leave for you to discover in the text.

For my loyal readers who were here last week, The Son was everything Violeta promised to be and failed to deliver - and then some. It’s hard to even make the comparison, so I will focus on The Son, and you can fill in the similarities and differences in your own mind. This novel spans more than 100 years. Eli himself actually lives to be 100, and we get extra years, up to 2012, from Jeannie. Naturally, a great deal of history is covered, or more appropriately put, lived through by our characters. Though this is a novel about Texas, it is really a novel about the United States, and in this regard Meyer absolutely knocks it out of the park. There’s the annihilation of Native American tribes and the subsequent relegation of what remained of those tribes to reservations across the US. There’s the Civil War, World War I, World War II, and even the Iran-Iraq War. We get racism, women’s rights, immigration, and more - historical events and issues that are important to understanding the fabric of America as a whole.

Instead of carelessly dropping these events and issues into the plot and crossing them off his checklist, Meyer actually incorporates them in a meaningful, and more importantly historically accurate way. We don’t get a 21st century perspective on events of the past. The characters live through them, as the real people who did live through them would have. There’s no spin, there’s just truth (it’s eminently clear that Meyer did his research), and the reader is left to do the rest of the work themselves - to understand how horrible or beneficial, or confusingly both, certain moments in history were. It’s much more rewarding than being treated like a child who needs to be force-fed an interpretation along with the facts. And while we’re on history, extra points to Meyer for treating as obvious the fact that LBJ and the Texas Democrats orchestrated JFK’s assassination.

Now, in order to get us where I want to go, I will briefly touch on the structure of the novel - namely the aforementioned triple narration. I don’t always enjoy novels in which the author alternates perspectives, because when done poorly, the chances of caring about only one perspective are dangerously high. I was even a little worried early on because Eli’s chapters describing life with the Comanches were so much more interesting than Peter and Jeannie’s. My worry was unnecessary, however, because much like everything else, Meyer nailed it. In the beginning Peter and Jeannie’s chapters are short compared to Eli’s. Right around the time that Eli’s chapters become less interesting (I’ll let you guess when that happens), Peter and Jeannie’s become more interesting. At the same time, Eli’s chapters get shorter, Peter and Jeannie’s get longer, and they meet in the middle. This is, of course, an oversimplification - it’s all extremely interesting, and essential to the story, but you get the point.

The other thing I noticed about Meyer’s form, which contributed to the overall effect of the novel, and which I view as a stroke of genius, is the fact that each character has their own narrative style. Eli’s story is told in the first person, Peter’s through journal entries and Jeannie’s in third person omniscient. As far as the level of interiority produced, these are not huge differences, but they do make a difference. Eli is the base of the story. Everything else that happens is informed by his life and his actions. Writing his story in the first person (and starting with him) means that the reader feels as though they know him best. The methods of narration used in Peter and Jeannie’s chapters closely correspond with the core elements of their characters. Peter is introspective to the point of overthinking. In his journals, he reports the events of the day, reflects and ruminates. Jeannie is distant, with a hard outer shell, but she has depth. Her life is written about in the third person, but we still go inside her mind. As the reader, you feel most closely connected to Eli, so when you’re reading Peter and Jeannie’s chapters you are able to pick up the thread of Eli’s life easily. Simultaneously and subtly, though, Meyer is ensuring that you know and care about Peter and Jeannie just as much.

Ultimately, plot and structure come together into a clear central theme: the past may be the past, but the past also lives. Our actions have consequences for ourselves and for all those who follow. In a way that is unsettling but not disturbing, Meyer shows that time is not linear. Although we are - I am - almost 200 years removed from the earliest events in this novel, the chain that leads from then to now lurks in the shadows, waiting only for some slight exertion on my part to come out and be made sense of. It’s more than that though - it’s not just the feeling that my forefathers (in both the literal and broad metaphorical sense) are in many ways responsible for creating the world I live in. Meyer is able to create the sense that I am also present in their actions. Considering the subject matter of this novel and the horrors of the past, I would expect this to weigh heavily, but it doesn’t. It weighs comfortingly, if that’s a thing. The interconnectedness of humankind defies time and space, and despite the parts of our past that must be reckoned with, I suppose that will always be a comfort. It’s a hard feeling to put into words, but I hope you’ll catch my meaning, and I hope you’ll read The Son and feel it for yourself.

Honorable mention for one of the best sex scene I’ve read, and definitely the best loss-of-virginity scene I’ve ever read, EVER. I’ll give you a little preview because there’s nothing I can say about it that will be better than this quote: “Then he began to take over and she forgot herself for a moment, then remembered again and began to wonder if the only reason they made such a big deal about the pain was to keep you from doing it every minute of your life” (Meyer 341). If that doesn't make you want to read this book, then I don't know what will.