The Things That Happen in Savannah

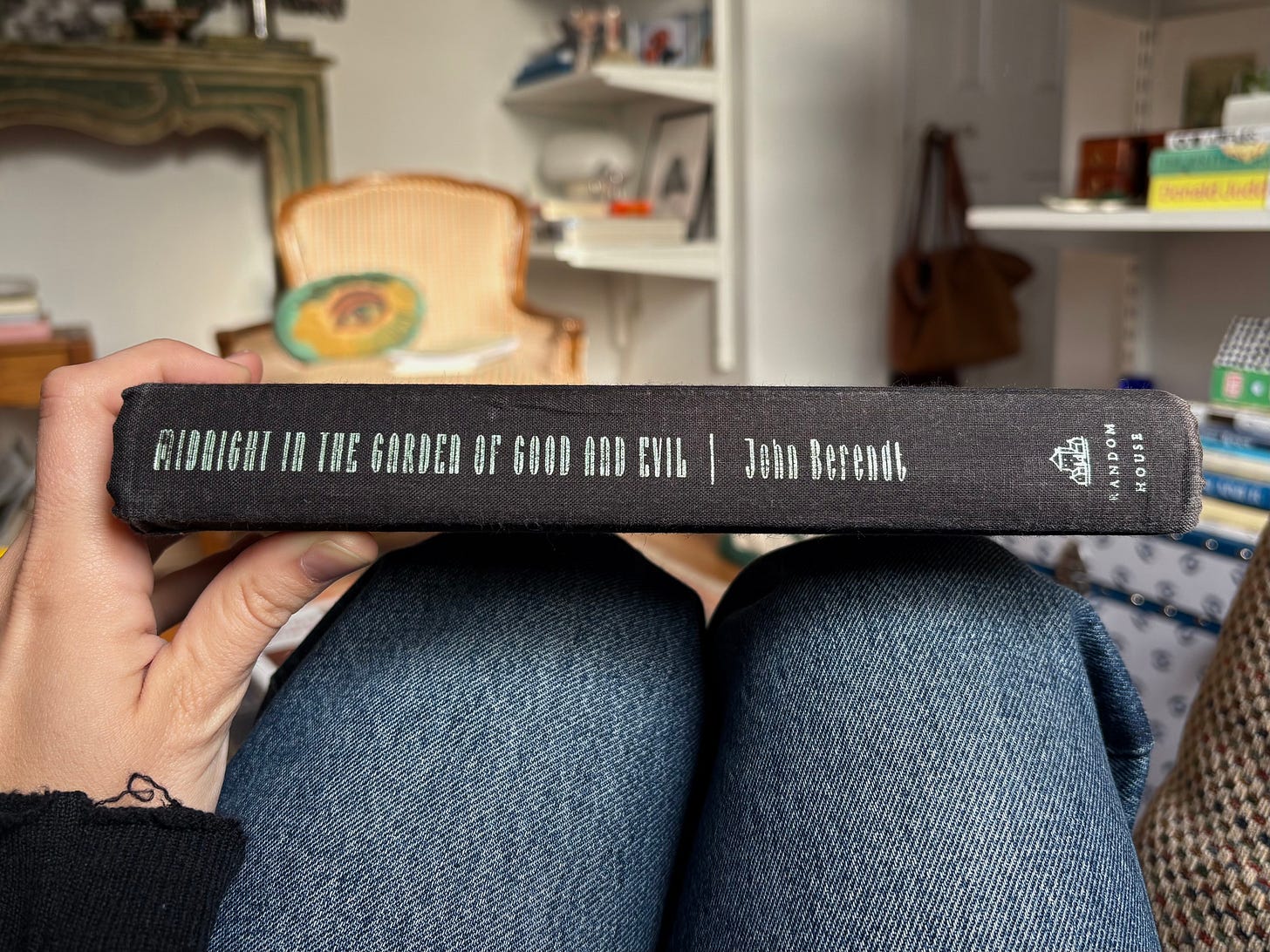

Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil by John Berendt

A couple weeks ago I found myself down in lovely Savannah for a wedding. I took the day off on Friday, so while my lover and our friends worked away in our barren Airbnb on Broughton Street, I wandered out. I had an inexplicable urge to visit the aquarium, but Savannah doesn’t have one, and the UGA Marine Education Center 30 minutes outside of town looked a little…sad.

That dream thwarted, I did what I always do, which is identify a bookstore and start moving in its direction. In this instance, The Book Lady Bookstore on Liberty, which turned out to be very good. I perused but eventually felt antsy to be back outside. The sunshine, the trees, the light breeze—it was all completely conspiratorial. I picked up Flannery O’Connor’s complete stories and Childhood Farewell, a 1962 book of poetry by a young man named Al Egan Walls, and made my exit.

Down the street, I almost got roped into an interactive movie experience (??) when I strolled through the SCAD building on Madison Square. But by then I had quickly googled Savannah historic house tour or something to that effect, clicked on the first link, searched the first house on the list therein, and discovered it was a mere four blocks away bordering the next square I’d run into anyway (Monterey). I was determined to go there, so SCAD had to wait.

As it happened, the house in question was The Mercer Williams House. Set back a bit from the street, leaving room for a well-manicured lawn and a couple of palmettos, the red brick facade of the house is beautiful but not particularly imposing. It is only walking around back to the entrance through the carriage house that one realizes it takes up the whole block, with a walled garden in the center.

The carriage house has been converted into a gift shop, mostly stocked with kitschy homewares irrelevant to the history of the house—except in one corner where a small-scale replica of a vaguely familiar statue sat surrounded by even more, even smaller-scale replicas of the same and tidy stacks of books. The statue is the Bird Girl—a young thing with a girlish haircut standing in a sweet looking button-up dress, head slightly cocked, with vacant eyes. She holds in each palm, upturned and held out to her sides, a shallow dish, and thus looks like an old-fashioned scale. The stacked up books? Copies of John Berendt’s wildly popular Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.

The tour began and we learned that no Mercer had ever lived in the Mercer Williams House (blame it on the Civil War, tuberculosis, etc.). The land, the building materials (unbuilt) and the John S. Norris blueprints (unexecuted) were sold to a man named Wilder who put the thing together. The house changed hands a couple more times, fell into disrepair for some years, and was eventually purchased and restored by art and antiques collector/dealer, and house-restorer-extraordinaire, Jim Williams. The very Jim Williams that Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil is all about!

I kicked myself for not reading the book before coming down to Savannah. It was sitting on my dresser at home. I hoped that the tour would focus more on the architecture and design of the house, the art and antiques housed there. I committed myself to letting any and all allusions to the specifics of the tale itself just kind of breeze by me. I somewhat succeeded. Jim died over here. The boy killed him inches from where he killed the boy. 200 something inches. Kevin Spacey. Danny was shot right where you’re standing. The bulldog next door, the organ upstairs, the famous Christmas parties, tried for murder four times, that was a record. It was all very intriguing—exciting!—but I couldn’t make much sense of it.

The little breadcrumbs were enough to sell me though—almost immediately upon my arrival home I cracked open the book, and two days later I had finished it.

Midnight is Berendt’s account of the time he spent in Savannah in the 1980’s with Jim Willaims’s first, second, third and fourth murder trials as a kind of grounding centrality. I quickly learned, however, that my tour guide’s claim—that the book was all about Jim—wasn’t entirely true. It is a work of non-fiction, but since Berendt takes certain temporal liberties and recasts certain second person accounts into the first person, the whole thing reads like a novel—but a novel that’s as interested in sketching out its characters as it is in any courtroom plot.

In fact, I would describe this book as a braid, with three distinct strands of importance and intent. The first strand is for the people. The whole first half of the book reads like a collection of character sketches. There’s Joe Odom—the charming lawyer turned piano player who flits from house to house, throwing the liveliest parties and leaving a trail of bounced checks in his wake. There’s Luther Driggers who walks around with flies on strings like a bunch of bumbling balloons and who threatens to poison the city’s water supply. His lady friend Serena Dawes who rarely rises from her bed, and favors marabou feathers when she does. There’s The Lady Chablis, a wild and charming black, transgender performer who unilaterally decides that Berendt will be her chauffeur. I could go on and on—Lee Adler the preservationist (and opportunist?), Minerva the voodoo witch. These colorful characters populate the pages of the book and keep the reader entertained before anything is really said or done about Jim Williams.

And those are just the characters that really recur. I fell in love with Berendt’s way of describing the more minor figures who populated the city past and present. Dr. Glover walks an imaginary dog. Big Emma won’t let anyone else drive her Mercedes limousine, so her chauffeur sits in the back and her German shepherd sits in the front. There’s Jerry who cuts hair in Joe’s kitchen, and on the other end, the Married Women’s Card Club and the proper, gossiping young couples it attracts. There’s the Alphas and the black debutante ball and Vera Dutton Strong who breeds thoroughbred poodles.

Interestingly, all of these people invited Berendt into their circles. He actually goes to the Married Women’s Card Club and the black debutante ball. Even the people who know he’s writing a book are inclined to share juicy secrets with him. Many of them are excited at the prospect of appearing in its pages, like Joe Odom fancies that he’ll come out of the jumble as a hero. As far as I can tell, they were mostly right to trust him. Berendt treats his ‘characters’ tenderly.

Nowhere is that more clear than it is with Jim Williams himself—the man on trial (once, twice, three times, four) for murder. That would be the second strand in this braided tale. The death of Danny Hansford and the subsequent legal proceedings. I’ve already given much away by sharing the number of trials, so I won’t say much about the details beyond that. Berendt does courtroom procedural well, and the promise of plot does a lot to keep the reader engaged through a first half that, while lovely and entertaining as outlined above, is not entirely going anywhere.

I found myself rooting for Williams and then not and then rooting for him again and then not. That’s what was so wonderful about the book: Berendt never tells you what to think. He doesn’t pass judgement—on Williams or any of his other characters. he doesn’t opine. He portrays his characters and their behavior with curiosity and interest while maintaining a detachment that allows the reader to decide what they think. For me, the effect was one of pervasive fondness, even when the characters behave badly or make questionable decisions.

Perhaps it reaches a level of indulgence—not just in Berendt’s writing but in the Savannah of the 80’s. Perhaps the people portrayed by Berendt as conniving, snarky, snobby, racist, sexist, homophobic, etc. etc. by today’s standards should have been brought to account. Either in the moment, at the time, or after the fact by Berendt. But he clearly didn’t see that as part of his job. In the Savannah he portrays it wasn’t anyone’s job to punish or oust people for bad behavior. It was their job to figure out how to coexist, and coexist they did—with only a murder every once in a while.

Which brings me to the third strand—I haven’t forgotten! The last one is for Savannah, the city that provides the environs indulged the good and the evil, and was therefore interesting enough to write a book about. Just a few decades after Berendt himself, I too discovered that you don’t have to walk more than about two blocks in the Historic District of Savannah before you get that glimmering feeling in the pit of your stomach. The one that says, things have happened here. And then it sets in—the curious certainty that if you lived here, things would happen to you too.

I didn’t edit this because I’m gone fishing. Ignore typos and poorly constructed sentences. Love you, bye!

This was one of the first true-crime novels I ever read and fell in love with. Berendt's retelling of these events was so rich and dramatic. I love that you found this book the way you did, Eve!