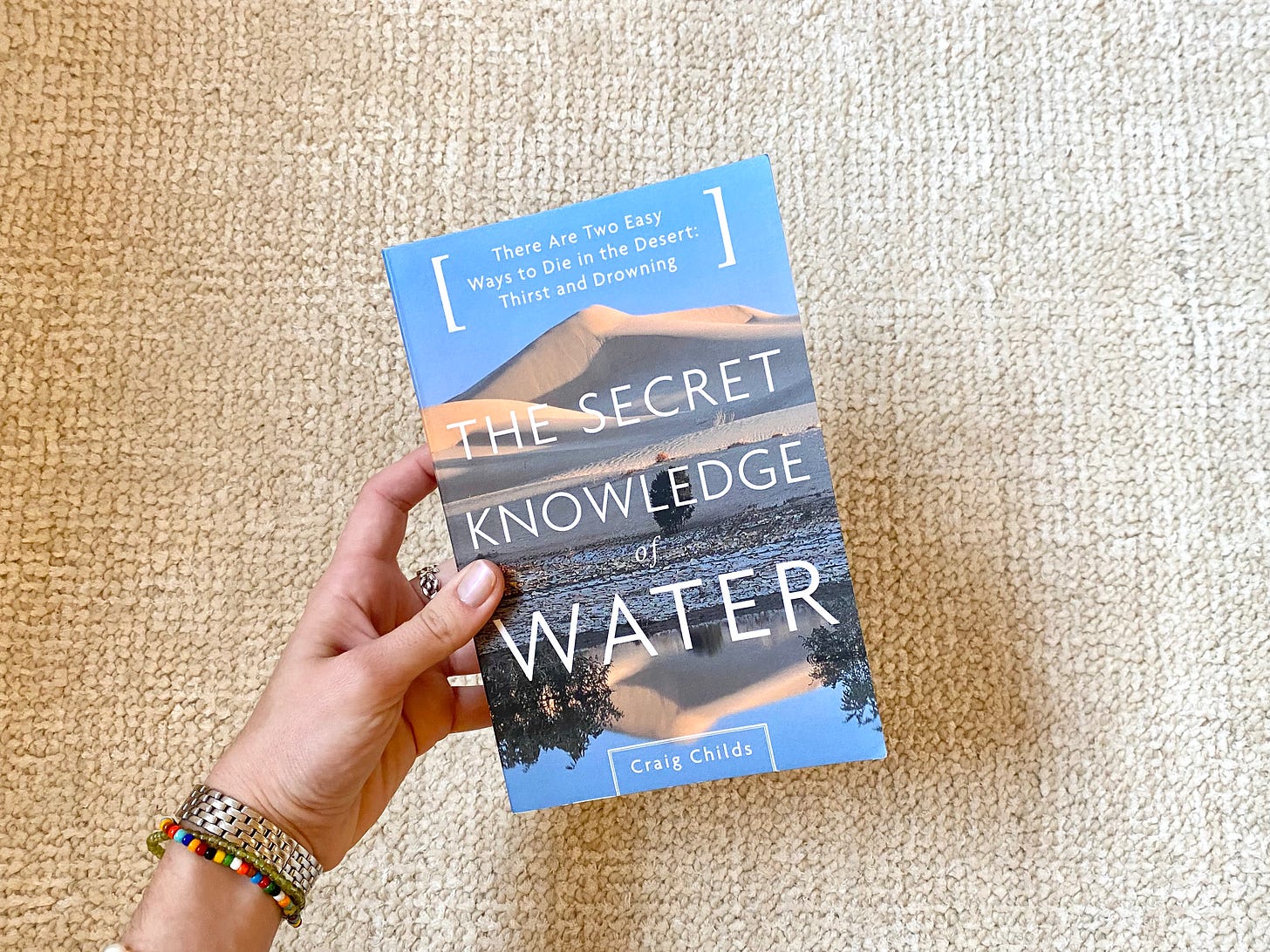

Thirst and Drowning

When I started reading The Secret Knowledge of Water by Craig Childs, I was nervous. I don’t read much nonfiction—which is not to say that I don’t enjoy it when I do—it’s just not my go-to. I hear about, or read about, nonfiction books, and I think to myself, “that sounds so interesting,” and then I add it to my to be read stack, and then I always pick something else instead. I guess I worry about getting bored, which I know sounds silly. It’s harder for me to slog through a nonfiction book that I’m not particularly interested in than it is to get through a novel that doesn’t speak to me. And I never give up on books in the middle (ever), so perhaps my hesitancy around nonfiction is an attempt to protect myself from getting trapped with a book that I don’t really enjoy. But that’s dumb! That there are so many wonderful, interesting nonfiction books—beautifully written to boot, and The Secret Knowledge of Water has served as an excellent reminder of that fact.

It took me about a week to get into this one, which is mostly due to the fact that I do my reading before bed. If I’m drifting off to sleep as I read at the beginning of a book, I end up reading ten pages the first night, and then the second night I have to go back, so I start at page five, and only make it to page fifteen, and the pattern continues. This is particularly true with a book like this, without a structured plot to carry me along. However, once I broke through (which, by the way, didn’t require getting to a certain page number, but rather reading a certain number of pages consecutively), I was pretty much thinking about this book at all hours of the day. As someone who mostly reads novels, it’s such an interesting feeling to be craving a book like this—itching to pick it up and read even if it’s only a quick three or four pages.

This is, of course, a testament to Craig Childs’s talent. I was eighty-five pages into the book when I got on a flight to Utah last Friday. I thought I was setting myself up perfectly to split the rest of the book between that flight and my flight home. You know how book planning goes. No such luck. By the time I got off the plane, I only had thirty pages left. The important context here being that the book is 273 pages long — I should have mentioned that first. It’s a 273 page masterpiece. Enough numbers though. It starts slow and picks up pace as it goes. Thematically, Childs moves from waiting water, to moving water, to fierce water. As such, the tone gains momentum from one section to the next — as the stories become more intense, the writing becomes more confident.

Childs’s voice is powerful, and the way that he writes has a certain element of gravity, while remaining effortless. When he talks about the places he’s gone and things he’s seen, it feels as though you’re inside his brain — looking out through his eyes, and also feeling his emotions. There are lengthy descriptions of the deserts, springs, and canyons he traverses — sitting water, dripping water, raging water. And there are contemplations of complex themes — life, the human influence on the natural world, death, and so on. These descriptions and contemplations build up until, like a flood suddenly filling a canyon, they dip into real stories, (sometimes tragic, always mind blowing) that make the whole thing so painfully human. Childs effortlessly takes things from a planetary scale, so big you can barely fit it in your brain all at once, down to a personal, could be you or your neighbor, level.

In addition to these impressive literary accomplishments, there is a beauty and brilliancy to the actual words he uses. It’s like poetry. For example, when describing a large stretch of water pockets on the Arizona-Utah border, Childs says “We returned at night and I lingered at the dance-floor pockets, near our small camp. Stars of a moonless sky reflected from the water so that the sky looked as if it had shattered and fallen messy across the earth.” Or there’s a particular passage on a canyon on the Southern Arizona, Northern New Mexico border described as “a museum of ecological oddities” where Childs spots a rare and magnificent bird. The excitement and wonder is palpable through his very intentional word choice.

One other thing that really stood out to me was Childs’s incredible use of metaphor. As I’ve said, the entire book takes on a very poetic tone, but interestingly enough, Childs uses these devices to snap the reader out of elevated, or even detached, passages back into the real world. For example, in describing a quickly building flood he says, “It rolled over the crystalline water below with the hasty resolution of a book burning.” Or this one, where he describes the end of a thunderstorm saying, “Sunlight arrived like a father bursting in on his daughter and her date making out on the couch. Fun’s over.” I mean, come on - absolute knockouts. These comparisons (among many, many others) slapped me in the face, and I thanked them for it.

I have so many other passages from this book that not only spoke, but screamed to me, but I realize that no justice can be done to them if you haven’t read the parts that come before. So I’m gonna leave them out for now and hope that what I’ve said is enticing enough to make you want to read it yourself.

More generally speaking, these types of books fill me with a low buzzing anxiety. I don’t know exactly how to categorize it, but there’s a quote on the cover of The Secret Knowledge of Water that really sums it up. It reads, “There are two easy ways to die in the desert: thirst and drowning,” and that’s how this book makes me feel. Like I’m thirsty for more and drowning in possibilities at the exact same time. Like this duality, the anxiety that I experience when reading about (or learning about in any other capacity) the magnificence of the natural world is twofold.

First there is the sense that we (humans) are slowly (quickly) but surely shrinking the area in which nature can be left undisturbed. Childs talks about this throughout The Secret Knowledge of Water, whether in regard to falling water tables due to overzealous drilling in the desert, or the near eradication of native desert fishes in Arizona due to the introduction of non-native Bass for sport-fishing. These things are terrible to read and know about. Why do we do this? Why do we think that we know better than nature? Aside from the straightforward environmental and ecological implications, it also represents a hubris that makes me extremely uncomfortable. When I read about and know about these things I can’t help but feel that we are wading into extremely dangerous territory (literally and spiritually speaking).

More than that, though, there is the sense that I won’t possibly be able to see all of the things that I want to see. Just within the United States, there are so many places, large and small, worth seeing and experiencing. This is my country, and I’ve seen a fraction of it, which feels wrong. Not even taking into account the rest of the continent, or the other continents, or the bits in between the continents, it overwhelms me to think of the things I’m missing out on.

I know these thoughts are not a productive, and when I share them with others, the reaction I get is almost always, “well, if you want to go see the world, do it,” and that’s fair enough. I think one thing that gets left out in this go-get-it, make-your-dreams-a-reality mentality, however, is the fact that everything in life is a trade-off. And that’s where I get lost. How does anyone choose their trade-offs? It has to be done, but genuinely, how do you do it when two disparate things - like traveling the world and being free and staying put, maintaining relationships, and being tied down (in a good way) - are equally important? And choosing one effectively rules out the other?

That doesn’t mean the reading and the learning isn’t worth it, though. Perhaps because of the fact that books like The Secret Knowledge of Water make me think about these things, I know that they’re worth reading. Aside from all that, what I really learned from reading this book, is that you should always, always read the books that people tell you to read (at least when they really mean it). Reading books that the people you care about care about is such a powerful way to be, and stay connected. There are parts of this book that will stay with me for the rest of my life, and that about covers my main criteria for a truly good book. So, thank you to my older brother Coleman Davidson, who gave me this book for my 24th birthday - without you I never would have read it, and I’m so glad that I did.