To Live & Struggle

Romola by George Eliot (EAGENOTS pt. 3)

My dear, dear readers! It’s time, it’s time. I’m back up on my soapbox for Eve’s Annual George Eliot Novel of the Summer—and, hard as it is to believe, just in the nick of time, too.

For those who are new here, or who have previously skipped over my rantings and ravings on Eliot, last year’s read was The Mill on the Floss, and the previous year was Silas Marner. The year before that, I read Middlemarch, but that was before I started writing about the things I read. Before that still, while in college (technically in the spring not the summer), I read Daniel Deronda. And before that still, I pretended to read Adam Bede for a different college class.

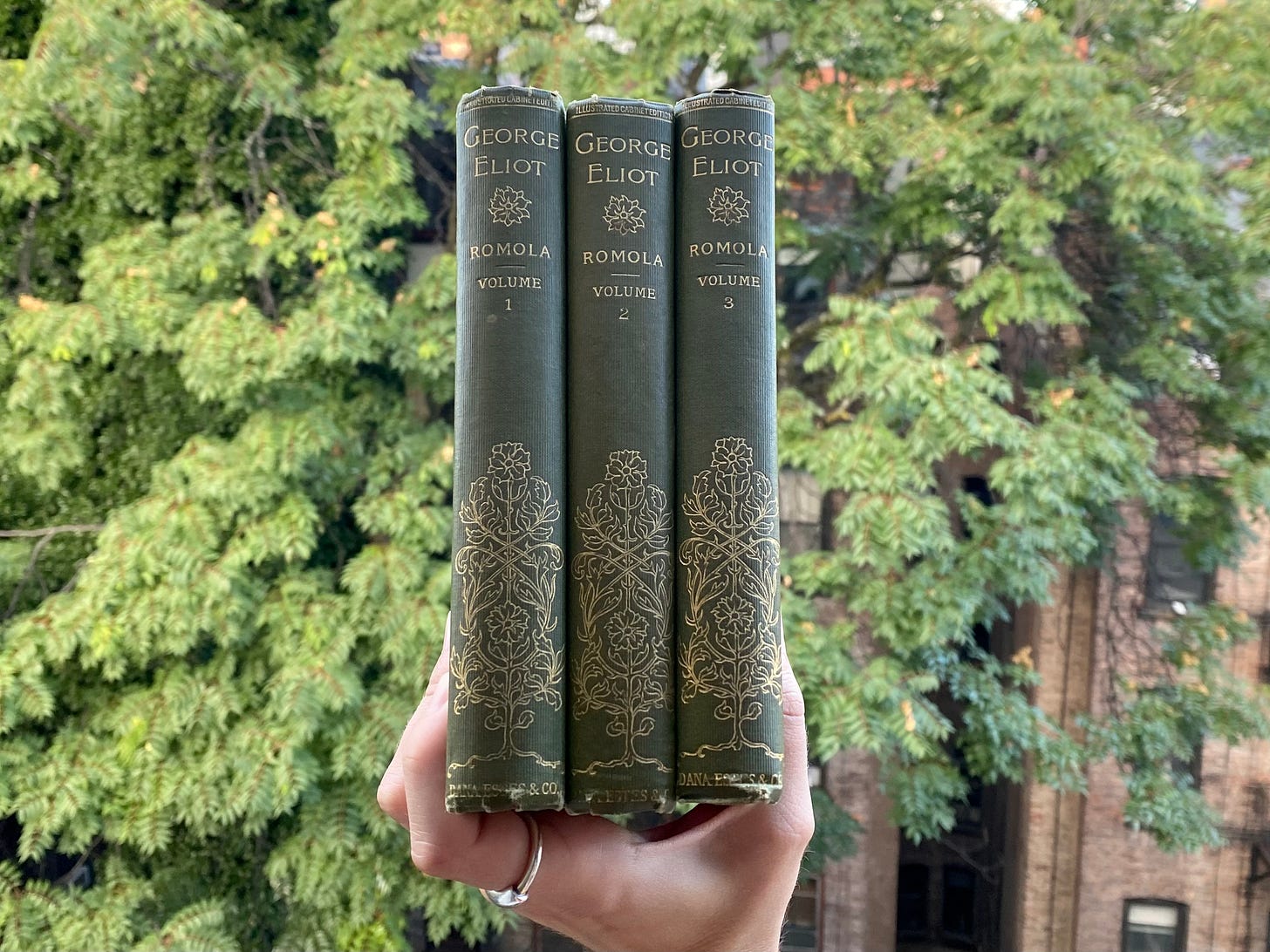

That meant I was choosing between Romola & Felix Holt, the Radical (and Adam Bede because I will have to actually read it one day). Faced with kind of the three least enticing options (or so I thought!) I chose Romola, though not least of all because of the old & fantastic edition I already owned, purchased at the Strand many moons ago. I don’t know when it was published because it doesn’t say (why not, Dana Estes & Co.????), but I did find the same version for sale online that allegedly has a gift inscription in it from 1904, so it’s at least 120 years old. I didn’t pay $45 for mine, though (cartwheels away flirtatiously).

The story, however, is even older than that. Published in 1863, and set at the turn of the 16th century in—no! Not provincial England, but Florence, Italy. My, my.

We begin with the death of Lorenzo de’ Medici. And here’s where I’ll go ahead and insert my disclaimer. This is the type of historical fiction novel (because that’s what it is and was—even at the time that it was published!) that is meticulously researched (Eliot spent years). Real historical figures and events abound. Though for the most part, our main characters are fictional, all that happens to them is tied to these real people and real events.

It’s a lot to take in. Machiavelli is there! Along with what felt like 17000 Cosimos? I know next to nothing about the history of Florence, aside from that it is very rich (literally and metaphorically). I also don’t speak Latin or Italian. Yeah, that’s right, there’s a non-negligible amount of non-translated Latin and Italian quotes littered throughout.

But you know what?! I have good news. An unexpected boon, really. My very old edition came with no introduction and next-to-no explanatory notes. This was a gift to me, because the only way I can be prevented from spending all my time flipping back and forth from text to notes text to notes text to notes while reading a book like this is for them to not be there at all. But also because it confirmed my belief that it’s really just not that serious. I feel like I came away with a full understanding of the Point, capital P, of this novel, and a decent enough grasp on the history stuff without the notes. I strongly recommend, as I do with all of Eliot’s work, just taking what you can and NOT WORRYING about the stuff that goes over your head.

Just…don’t read the explanatory notes, particularly if they make you feel like you’re doing homework (which they sometimes do). This is not homework. I have noooo doubt that with a little more context, Eliot’s takes on the real historical events she portrays—and the ways in which those events can be related back to her current moment and our current moment and, and, and—would be even more illuminating and layered and complex. But I’m good without that extra exposition.

I’m here for the characters that Eliot creates, for her uncanny ability to strip them naked (psychologically speaking, of course—don’t be ridiculous), and for her undying belief that though man is frail, he is also unparalleled in sheer capacity for goodness. So what of these humans—the ones she makes up?

Well, we have the story of Romola de’ Bardi, the beautiful and noble daughter of Bardo de’ Bardi a classical scholar of great integrity but little glory. Having lost his eyesight years prior, he needs Romola to fetch his books, read aloud to him and write his annotations and commentaries. She is utterly devoted to him, and together, they rarely leave the house. This is how they are, when one pretty-faced, smooth-taking Greek by the name of Tito Melema washes up in the city.

With his charm (and yes, that pretty face) he quickly infiltrates the political circles of the city, and gets himself in with the group of men who hang around Nello’s barbershop. As luck would have it, Tito is a scholar himself, and after being introduced to Bardo, he finds himself rather seamlessly inserted into the de’Bardi domestic scene (if you can call the dark library where they spend all their time a domestic scene).

Unfortunately, Tito, though perhaps good at heart, lacks moral fortitude. He worries most of all about his own comfort and pleasure, which sets off a chain of decisions—many of them seemingly infinitesimal—that will conspire to change Tito from a good person who does bad things into a bad person. And Romola, having been swept off her feet by him (yes even a woman of her stature and dignity can be swept off her feet), finds herself in a very uncomfortable front row seat to her husband’s devolution from a man she admired to a man she cannot countenance.

Eliot’s portrayal of this process from the inside of Tito’s mind is some of her absolute best work. He is not a man who is prepared to struggle against his baser impulses. Take as proof: “That problem of arranging his life to his mind had been the source of all his misdoing. He would have been equal to any sacrifice that was not unpleasant.”

Of the backdrop of political instability and the various forces vying for power, I will say little. I don’t have the space really. But I can’t not mention Fra Girolamo Savonarola, who for the bulk of the novel, sits squarely, though somewhat indirectly, at the head of the Florentine government. Savonarola is a real historical figure—a Dominican friar—who spoke out against corruption in the church and preached civic religiosity. In addition to this real and more lofty role, he also serves in our novel as a personal mentor of sorts to Romola, exerting a great deal of influence on her.

Romola has within her a demonstrated tendency towards self-denial in favor of fulfilling her sacred duties to those with whom she shares an honored bond. Look no further than the blind scholar father and the dark library. However, even the most dutiful reach an eventual breaking point. For Romola, when she thinks that she cannot bear it anymore and tries to run away from her disintegrating life, it is Fra Girolamo who stops her. He draws upon her inherent loyalty and makes her see that if she flees, she will only experience a more hollow form of suffering. On the other hand, the suffering available to her if she honors her ties—both personal in regards to her marriage, and civic in regards to her duty to her fellow Florentines—is a suffering worth…well, suffering through. How enticing! But enticed she is.

So Romola, quite opposite in nature to her husband, starts struggling. It is this struggling—this desperate fight to live up to the, admittedly probably too high, high standards of Fra Girolamo’s vision—that makes Romola such a compelling character. It is not easy for her. She falters. She doubts herself. She even doubts Fra Girolamo. But she continues to struggle towards goodness and rightness.

It is worth noting that she does so, guided by a deeply and fundamentally religious man, without being a practicing Catholic herself, in fact having been raised to scoff at, if not resent the church. Yes, her biggest struggle is to honor the bonds of matrimony, as defined by the church, but at the core of it is a more broadly applicable tenet: our duty to others is more important to our duty to ourselves. Per last week, our pleasure (or comfort) is not the most important thing.

And for Romola, it’s not the fact that she stays in her marriage—a relationship that I personally would never allow any person I love to stay in—but the fact that she continually wrestles with herself over the larger question of what a marriage bond means, what any bond means, that makes her noble. It is also what allows her to finally, break away. She has struggled, and she has asked of herself great things, and her soul has responded in kind:

It flashed upon her mind that the problem before her was essentially the same as that which had lain before Savonarola,—the problem where the sacredness of obedience ended, and where the sacredness of rebellion began. To her, as to him, there has come one of those moments in life when the soul must dare to act on its own warrant, not only without external law to appeal to, but in the face of a law which is not unarmed with Divine lightnings,—lightnings that may yet fall if the warrant has been false.

I found all of this captivating, perhaps most of all because it sometimes feels as though we (blanket statement) as a society have come to fear the struggle that makes us human and makes us good. The specific type of struggle I’m thinking of—on the battlefield of the conscience—is something that I don’t see reflected in much contemporary writing.

It feels like we’re inundated with novels that show the flaws of humanity, without putting their characters to work at overcoming those flaws. Where are the admirable ideals, the noble paragons? Where are the characters who painfully acknowledge their faults, who look at themselves with the questioning inward glance? Show me those who are adhering to a moral code when it’s easier not to, when no one will even know that they didn’t! That’s the kind of exemplary struggling that seems to be falling away.

We are instead, increasingly told to avoid situations that make us uncomfortable, to set our boundaries, to cut ties with people who “disturb our peace,” bring to an end relationships that are no longer serving us. SERVING US???? Of course there are real situations that come with their own warrants as per above, but as an overall approach, we’ve fallen into such a twisted perception of what it means to be bonded to another—whether romantically, platonically or familially.

It may not be fashionable, but discomfort and unpleasantness—and the mental struggles they induce, not only serve a purpose (growth) but in fact have a sheen of…I’m not sure why, but the word that’s coming to me is glamour. There is certainly nothing less glamorous than a person who cannot or will not take the time to mull over how preposterously difficult it is to be good. Nothing less glamorous than someone who isn’t willing to strive for goodness, despite how difficult it is.

And so, this is why I love reading Eliot so much. She reminds me that to live fully in this world, as a human with both love in my heart and trouble in my mind (for who among us can say there’s no trouble in our minds), is to STRUGGLE. She makes the struggle beautiful. She makes me want it.

&& the next episode of Something We Read, comes out the first week of September. Send reading (and non-reading) related queries to somethingweread@gmail.com <3 love u, bye

As usual, you amaze me. What a wonderful human, yet literary, and captivating review of a book I know nothing about. Now I want to find a beautiful set like that in the photo and read it at my leisure. I prefer lying on my sofa with my feet and legs elevated (Still nursing my sprained ankle when possible, though it is almost healed now.) But when I lie down both my dogs jump up onto me lying in heavy lumps along my body starting with my chest and lingering almost to my knees. Dachshunds are so loooonnnnggg. When my son's dog is with me the experience intensifies as he weighs more than 35 lbs and is longer by far than my two miniatures. Never the less, I am looking forward to trying to read this extraordinary novel.

what a fun review to read - well done eve! this was zesty and captivating