Translating & Rowing

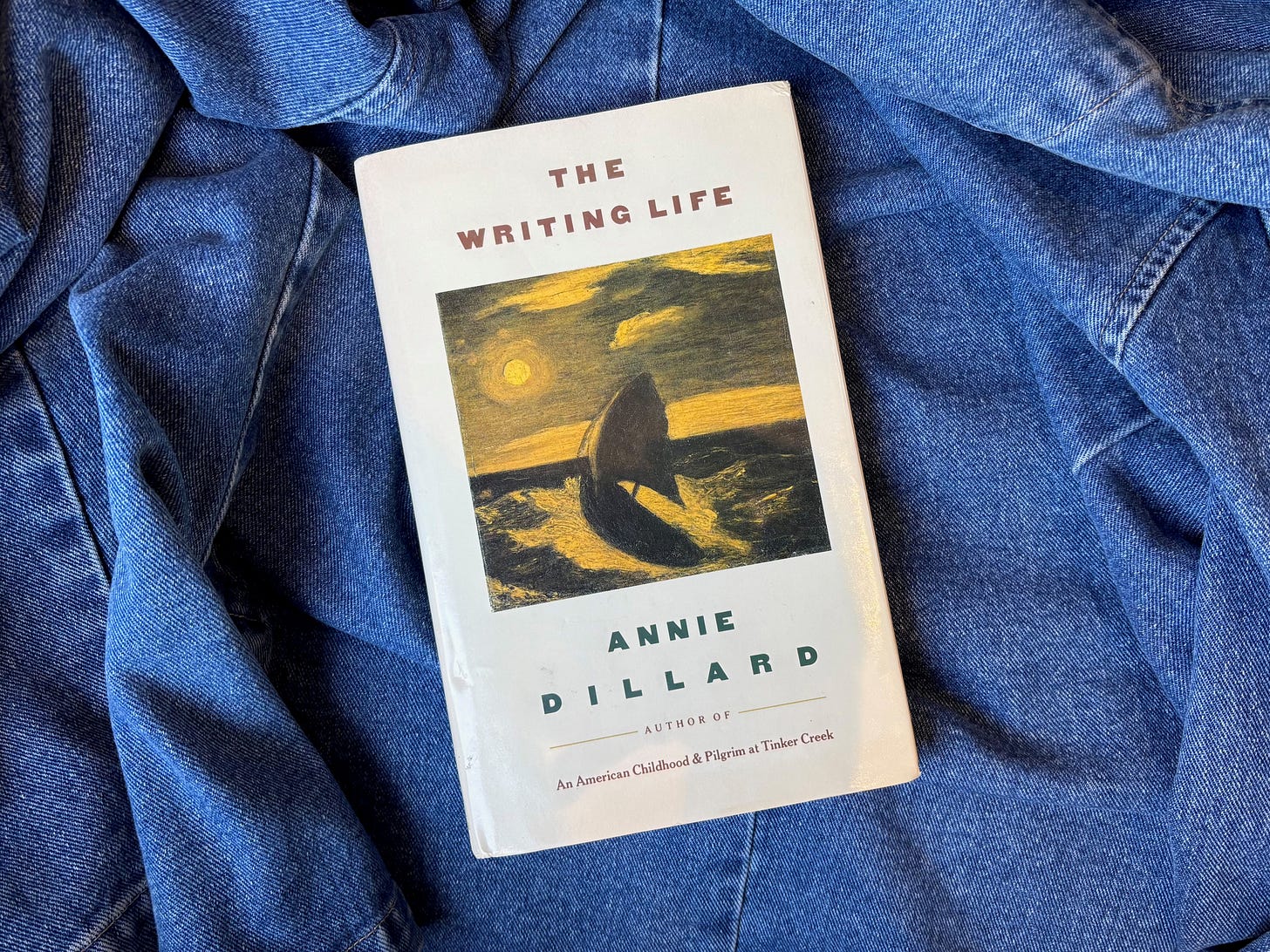

The Writing Life by Annie Dillard

My love affair with Annie Dillard (which started basically at random with Holy the Firm) continued in September with The Writing Life. She scares me, but in an inspiring sort of way. She inspires me in a crushing sort of way. I guess I’m more in love with her than ever.

This slim volume is in turns dryly funny and deadly serious. Dillard is a skilled storyteller, and more than that, a weaver. She jumps from one thing to another until suddenly, without realizing that you were holding the end of her unspooling thread the whole time, you end up somewhere profound. Exactly where she wanted you to be. Reading her is like eating a slowly coursed meal.

Her tone is humble—citing throughout this work in particular many other writers and thinkers. In one section she begins: “I have been looking into schedules.” She tells us about Wallace Stevens, Dante, Nietzsche, Emerson, and most admiringly, a turn of the century Danish aristocrat. She’s curious and wants to learn, if not from, then at least about how others have turned their good days into good lives. She says that at its best, the sensation of writing is that of any “unmerited grace.” The lines and sentences drop down on her.

Of course, the dropping down is not completely divorced from one’s efforts. She may not know where to look when it comes to the lines and sentences, but she’s quite self-assured in knowing how to look. Even as she writes this tribute (and her others) to the unknown and unknowable, she’s not confused about what she’s doing. In one passage, a neighbor of hers who works on a ferryboat, a “member of the real world,” asks about her writing and she unthinkingly says that she “would rather do anything else.” When he asks her why she does it then, she can’t imagine why. It’s not so much a choice. In this moment and others she’s very funny. Well, maybe not very by the standard definition, but I laughed.

She has a knack too for blurring reality and replicating the disorientation she so clearly feels moving through life. The reader can’t be sure whether she’s reporting real events that seem mystical, or mystical events that to her seemed real. In the middle of The Writing Life a typewriter erupts, shooting sparks out of “the dark hollow in which the keys lie.” The fire is largely contained, though she does take down the curtains and drag away the rug. In another moment a pair of first graders surprise her by seeming to understand her most symbolic and obscure essay, and in yet another, she plays chess against an unseen opponent in a locked up library. It may all be true.

As far as her writing advice goes, here is what I think most bears repeating:

What we read for, and thus what we write for too, is a representation of true “beauty laid bare, life heightened and its deepest mystery probed.” The writer, but really the artist more generally, catches glimpses of glories, visions and secrets. Then, he tries to translate them. The artist knows that he cannot translate them. The secret, the vision, the glory is inherently untranslatable. The artist must, is somehow compelled to attempt the translation anyway.

The glimpses when they come are simultaneously obvious and novel—i.e. something has just been revealed to me alone, and it is baffling that everyone else on the planet does not also already know this (including the version of me 10 seconds ago who didn’t know it). Even as logic tells you that it can’t be true, you suspect that no one else has ever seen what you just saw. Again, there is some light hunting involved. These moments cannot be manufactured but they can be…encouraged. Dillard says that “a writer looking for subjects inquires not after what he loves best, but after what he alone loves at all.” The glories are in the strange things that no one else seems to care much about. The things that force the realization that you are, in fact, alone in your mind.

Once you find that strange love, your awe and devotion demand that you attempt the translation. “You try—you try every time—to reproduce the vision, to let your light so shine before men.” Is there any chance of success? Well no, but also, that depends on how you define success. Dillard says that “the artist is willing to give all his or her strength and life to probing with blunt instruments those same secrets no one can describe in any way but with those instrument’s faint tracks.” Is there any other endeavor in which faint tracks count as success? And in writing, to achieve even that, one must be terrifyingly persistent.

Much of The Writing Life recounts the periods when Dillard was working on Pilgrim at Tinker Creek and Holy The Firm. The latter was written while she was living in the Haro Islands at the northwestern tip of the United States. She describes her encounters with some of the other characters who populate this remote land, including one with the painter Paul Glenn. He tells her a story about a man named Ferrar Burn who lived in the area 20 years back. One day, Ferrar spotted what he believed to be a nice log of Alaska cedar. A wet log is heavy, but by his estimation, it was small enough to pull it in with his rowboat, so out he rowed. He rowed and rowed north towards home, and as he did, the strong tide of the Haro Strait swept him south. Hours went by, and Ferrar got further and further from the place he was aiming for. But then night fell. The moon rose as it is wont to do, and the tide turned. So, Ferrar was swept home again with his log of nice Alaska cedar.

That’s really all there is to it. Keep rowing, and then when it’s over, try not to let anyone see the palms of your hands.

I read The Writing Life with Petya K. Grady & Regan, which was a real treat. They made me feel better about falling straight to sleep the first three times I tried to start it <3

Eve this is so beautiful!! Final 20 pages here I come...

I love this! I now must read this. I love reading books about writing. They provide a very particular type of inspiration and solace.