Vanishing Acts

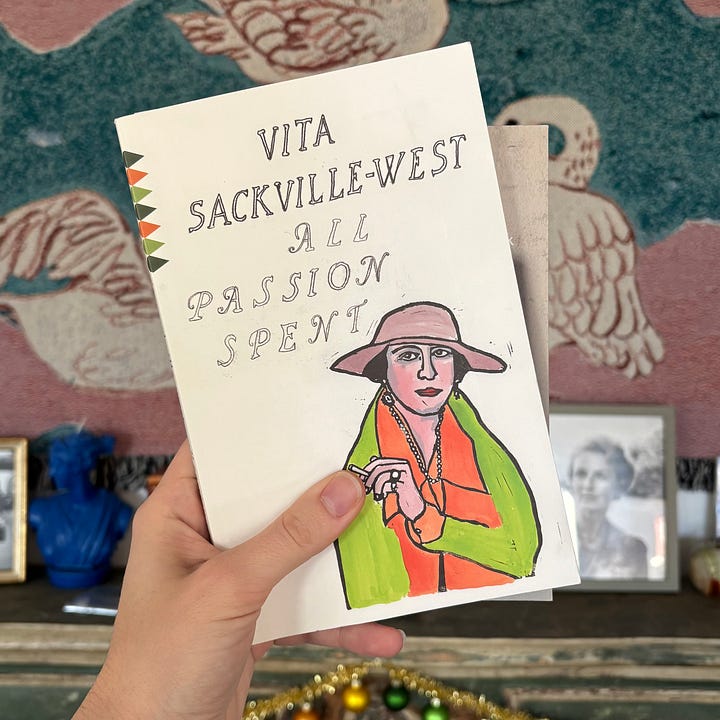

Last Month’s Reads: All Passion Spent by Vita Sackville-West & Things that Disappear by Jenny Erpenbeck

I will start by saying that I was supposed to read—nay was indeed reading—Doctor Zhivago last month, but I just couldn’t finish it. It was an ambitious choice for such a busy month, and that’s not even considering the fact that I generally find Russian literature totally unconquerable. I got 200 pages in, took too long a break from reading, and completely lost my tenuous grip on which names referred to which characters. Alas…

I decided something with a skinnier spine would be more suitable, and plucked All Passion Spent off my shelf. There was a vague (imagined?) memory of someone’s hot take somewhere on the internet claiming that Vita was a better writer than Virginia (Woolf that is), so when I saw it on the table at Three Lives, I bought it. I don’t know if my praise for Sackville-West would go that far, but she is very good, and I was sold on All Passion Spent before the end of the first page.

Lord Slane, Former Prime Minister and viceroy of India, has died. He’s left behind, in addition to his exemplary record of public service and a pile of jewels, six children, their numerous progeny, and his widow, Lady Slane. She is wonderful, or so her children keep saying in the hours after Lord Slane’s death, as though they are pleasantly but genuinely surprised by her ability to hold up under such a loss.

What comes next proves to be the real shock. Lovely, charming, self-sacrificing, and above all, governable Lady Slane has her own notions about how she’d like to spend the rest of her life, and is actually not glad to be guided by what her children think would be best. The children, though she loves them, are kind of a nightmare—particularly the eldest four. Lady Slane will retire to Hampstead Heath, where she may enjoy total restfulness and reflection. The children may come by, since she can’t exactly keep them away, but the grandchildren and great-grandchildren are not welcome. Their youthful energy would be too disruptive.

Amid the head shaking and hand wringing that follows her announcement, and the grand reveal of her own free and strong will, Lady Slane decamps, bringing only her devoted French maid, Genoux, with her. In Hampstead, She makes friends with her extremely eccentric landlord, Mr. Bucktrout, the local tradesman and undertaker, Mr. Gosheron, and eventually a reclusive art and antiquities collector, Mr. FitzGeorge.

It is a deliciously funny book, and perhaps not quite rollicking, due to the age of the protagonist, but close to it. It is also one woman’s moving reflection on a life that was full, like most well-lived lives are, of sacrifice. In particular, a young Lady Slane, Deborah, harbored an unrealized, and even untested dream of being a painter. She considers what she lost when she gave it up to marry a young Henry Slane. She considers the parts of her that did not die but were folded away when she stepped into what would ultimately be her main role of life: the wife of a diplomat.

If that sounds a little bit depressing, I promise it’s not. Lady Slane, like all the best old people, is honest, but she is not bitter. Somehow, through her, Sackville-West walks the narrow line between endorsing a kind of selfish prioritization of the independent and artistic life and recognizing the inestimable value of love and human fellowship, which inevitably requires sacrifice. The end is also perfect.

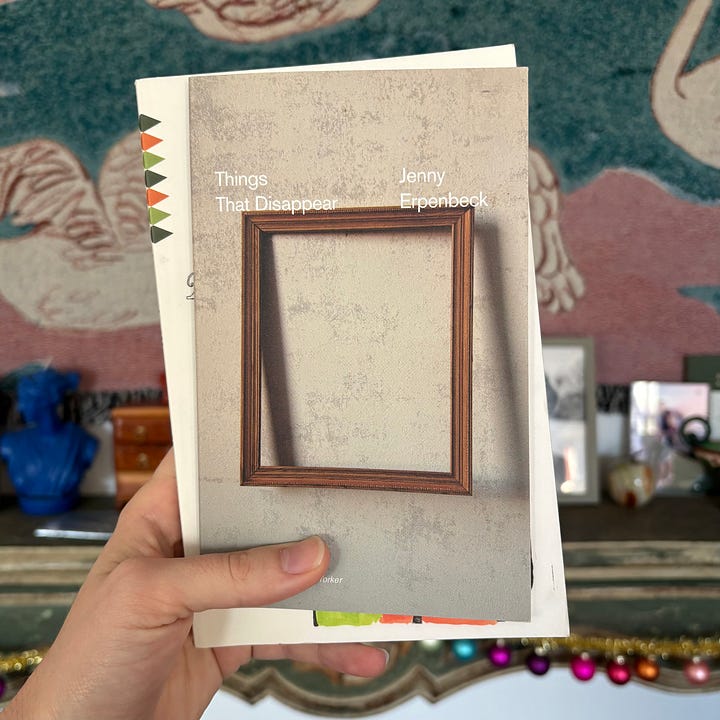

After All Passion Spent, I went even skinnier (spine-wise) with Things That Disappear by Jenny Erpenbeck. I bought this for myself and had it wrapped to go under the tree, from Eve, love Eve. My sister also bought it for me, wrapped it, and put it under the tree. Great minds.

Things That Disappear comes in at a mere 71 pages and is made up of narratively disparate but thematically linked vignettes. What happens when things disappear? Why do some things go while others stay? Where do the things that go go to? Are we supposed to just let them go? Erpenbeck was born in 1967 in East Berlin, so her scope ranges from the very broad (entire countries and cities, their architecture and character) to the highly particular (socks & shops where you can get your stockings mended).

Early on, in a chapter titled “Junk,” Erpenbeck contemplates the “Japanese Style” of living—sleek, no knickknacks, no dust—that has become so popular. Her house comparatively is fully of junk. When she recounts a move towards the middle of the book, she says, “so many things have grown attached to me and have to disappear with me when I leave.” This includes the wooden planks of disassembled treehouse. The things she has amassed and lives with come up again later when a Russian woman visits her apartment and finds it all so lovely. She recently moved to Germany and couldn’t bring everything with her.

This is, of course, a central condition of life, and one that we fight against to varying degrees depending on our brain chemistry (I guess): you can’t bring it all with you. There may be something to the idea that practicing—letting go—is good preparation for what’s to come, but Erpenbeck is clearly a collector. She collects things, but also ideas and memories, through which she can create an afterlife for the things that have gone, or are going.

Much like All Passion Spent, the book is in turns deeply moving and winkingly funny. A small piece of expensive cheese vanishes into thin air, and she likes it, actually, when a gentleman helps her into her coat, though that type of courtesy seems to be on the way out. Also gone is the simple life her great-grandmother used to live. There was an outhouse, an open fire in the kitchen, and a bucket of water to wash your hands, which all seems archaic now, but was just fine at the time. One section on Splitterbrötchen, a now difficult to find German pastry, ends with the following: “I’m not interested in the variations, I’m interested in the essentials. Today’s Splitterbrötchen is something fundamentally different from the Splitterbrötchen twenty years ago.”

While somber at times, Erpenbeck’s writing never feels pessimistic or hopeless. It’s not really hopeful either, it just is. She opens her hand to her reader, and it’s full of shiny little things. She says, “Look, these things existed once and no longer do. These things exist but soon will not. They might be worth holding onto.”

thanks for reading, bye <3

Your essays bring me such joy! Thank you for sharing your lovely words with the world!

your last paragraph !!!! yes!!