One Hundred Times

poems all about the same thing

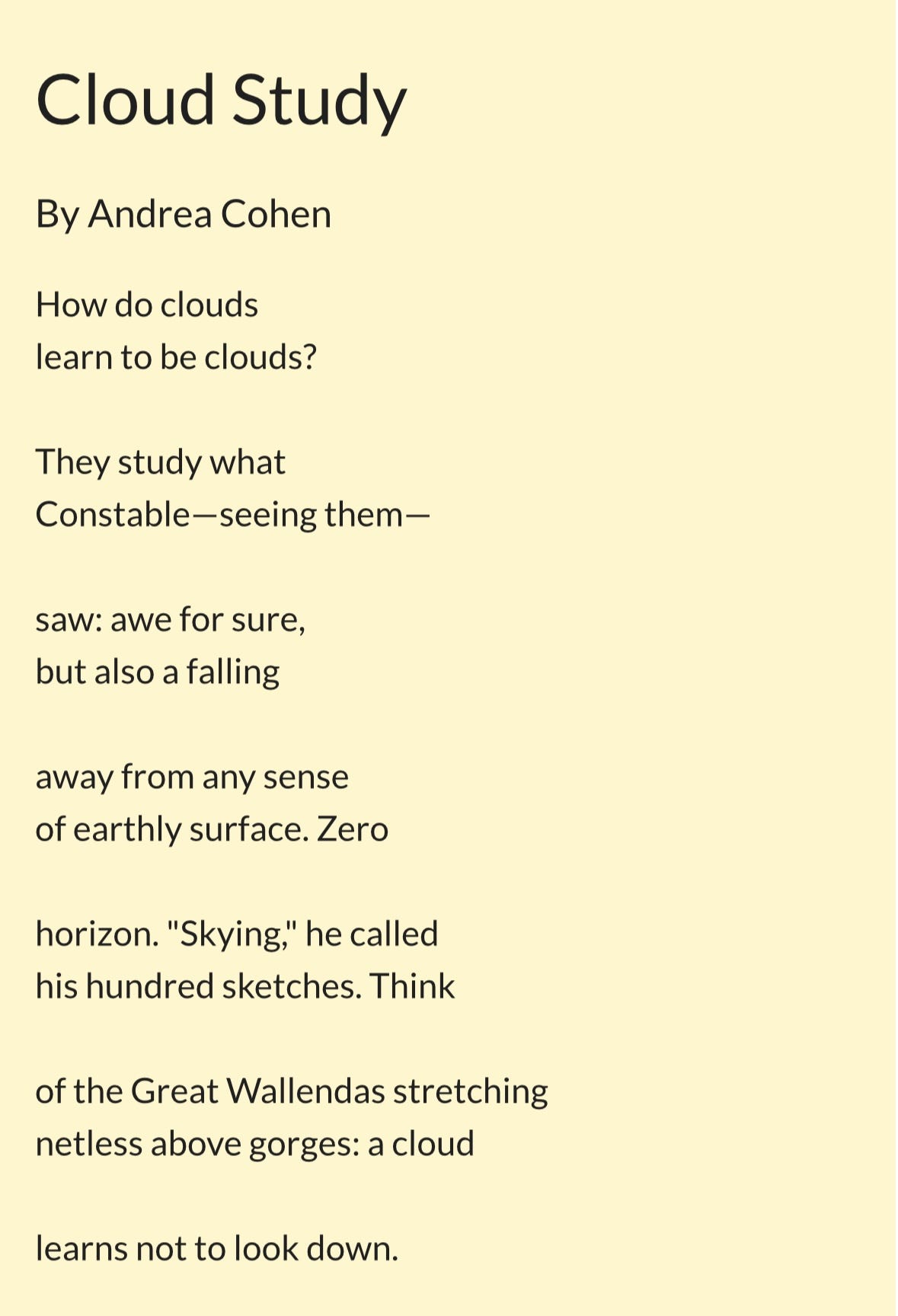

Last week, a favorite weekly poetry email1 landed the lovely “Cloud Study” by Andrea Cohen in my inbox.

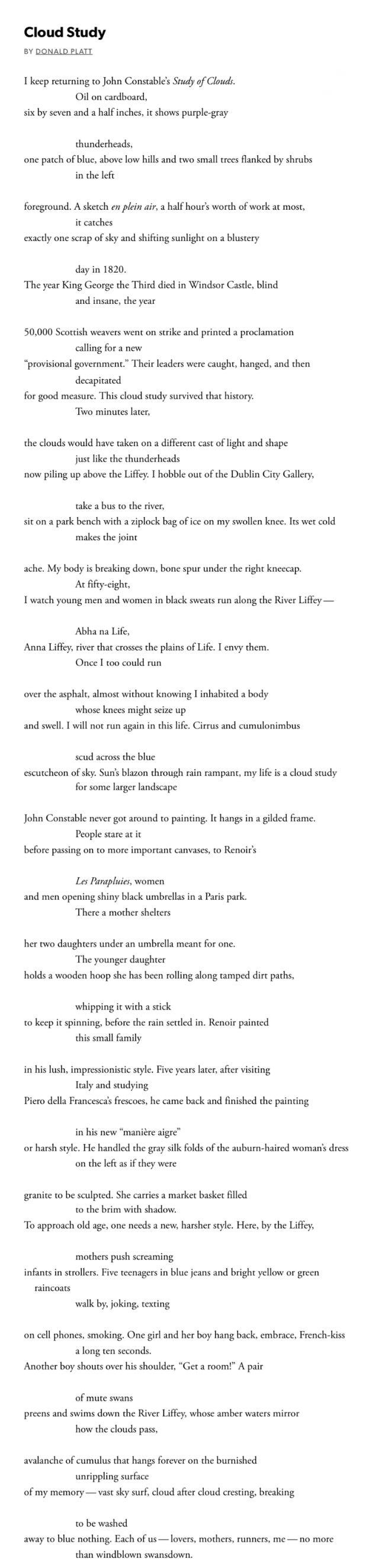

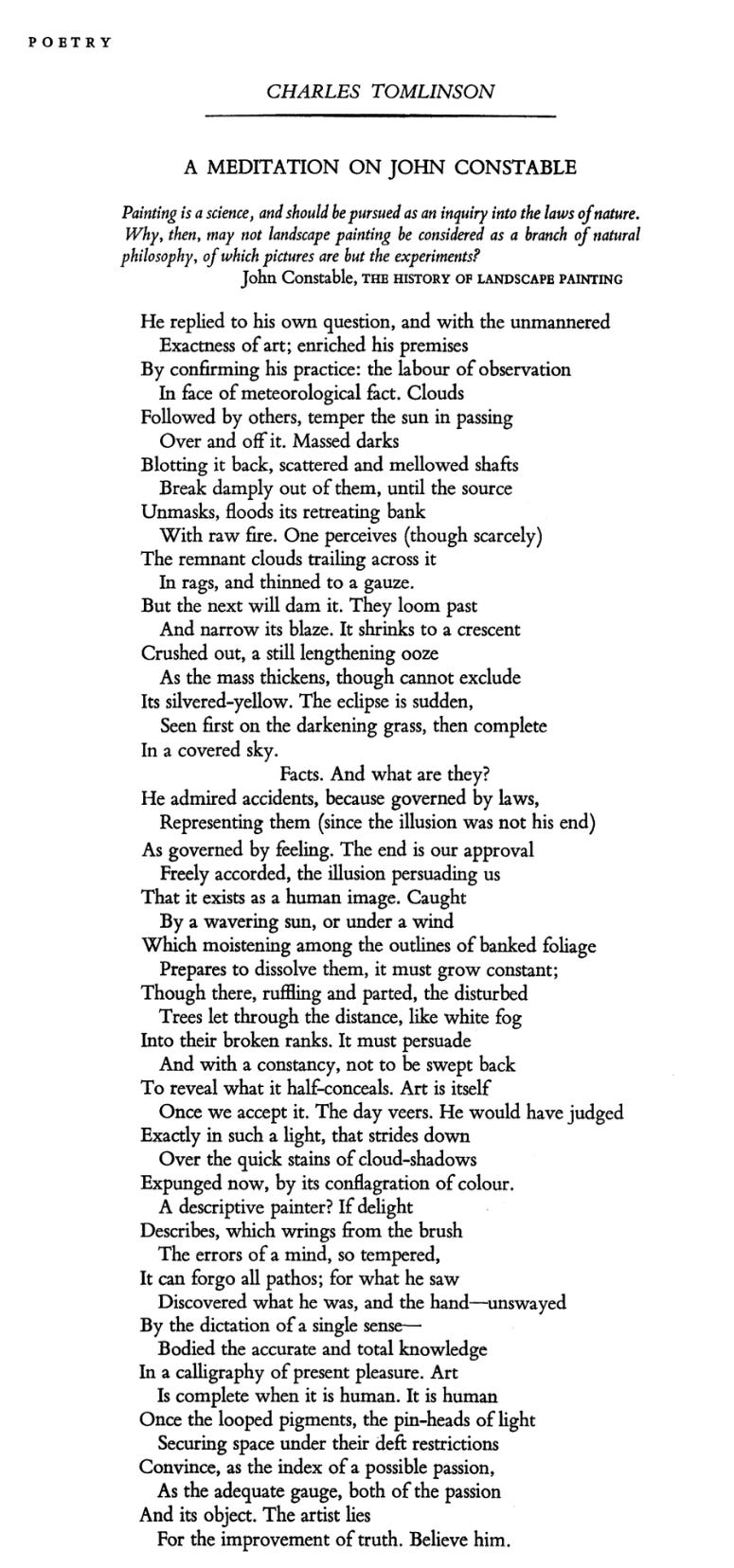

I was struck by the quite obvious realization that different people write poems about the same things all the time over and over again. This undeniable fact is of limited interest—par for the course—when the chosen subject is broad and general: love, birds, death. It is of greater interest when that thing is as specific as John Constable, for the thing seems specific, but the proliferation of poems seems to prove that it is not.

Cohen invokes Constable in wondering how the clouds learn to do what they do—sailing by and somersaulting around themselves, all while suspended in the sky. In a deeply pleasing turning of the tables she puts forth that the clouds learn to be themselves by studying what Constable saw when he studied them: the unimportance of the earth below (not unkindly meant).

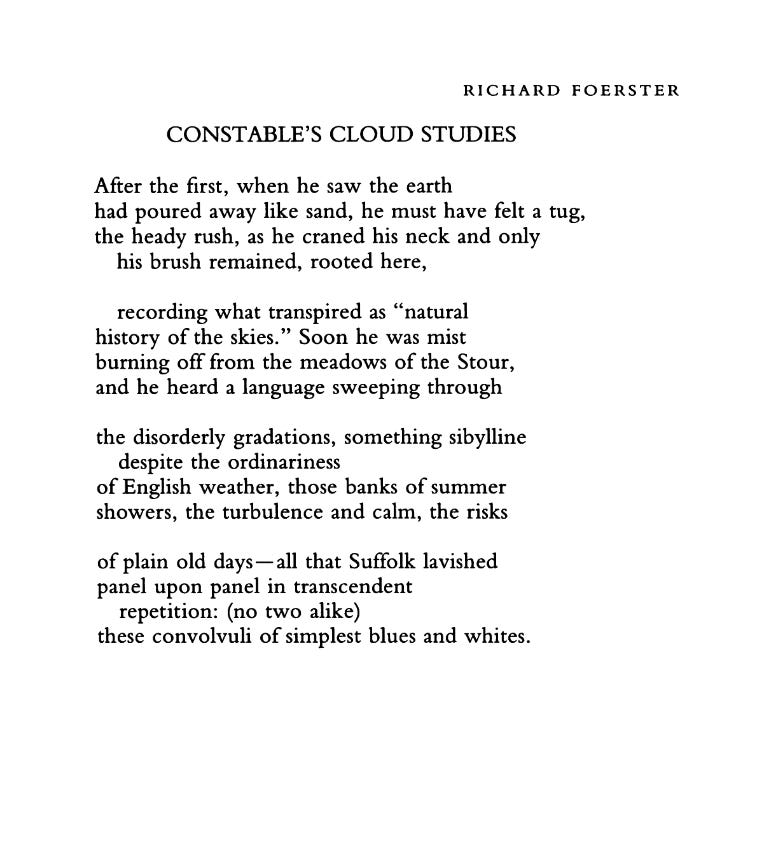

John Constable was an English painter in the late 18th, early 19th century. He was and is well known for his landscapes, many of which feature prominent cloud formations—often taking up half the canvas and certainly taking up and running away with any viewer’s attention. He himself believed—and wrote in a letter to a friend—that in landscapes, the sky would always be “the key note, the standard of scale and the chief organ of sentiment.”

It should be no surprise then that he dedicated himself quite assiduously to capturing the clouds. He did so over a series of summers in Hampstead, painting roughly 100 cloud studies—many of which featured no landscape at all. He ‘sketched’ them on the go while out in the countryside, and, as Cohen highlights, he called his practice ‘skying.’

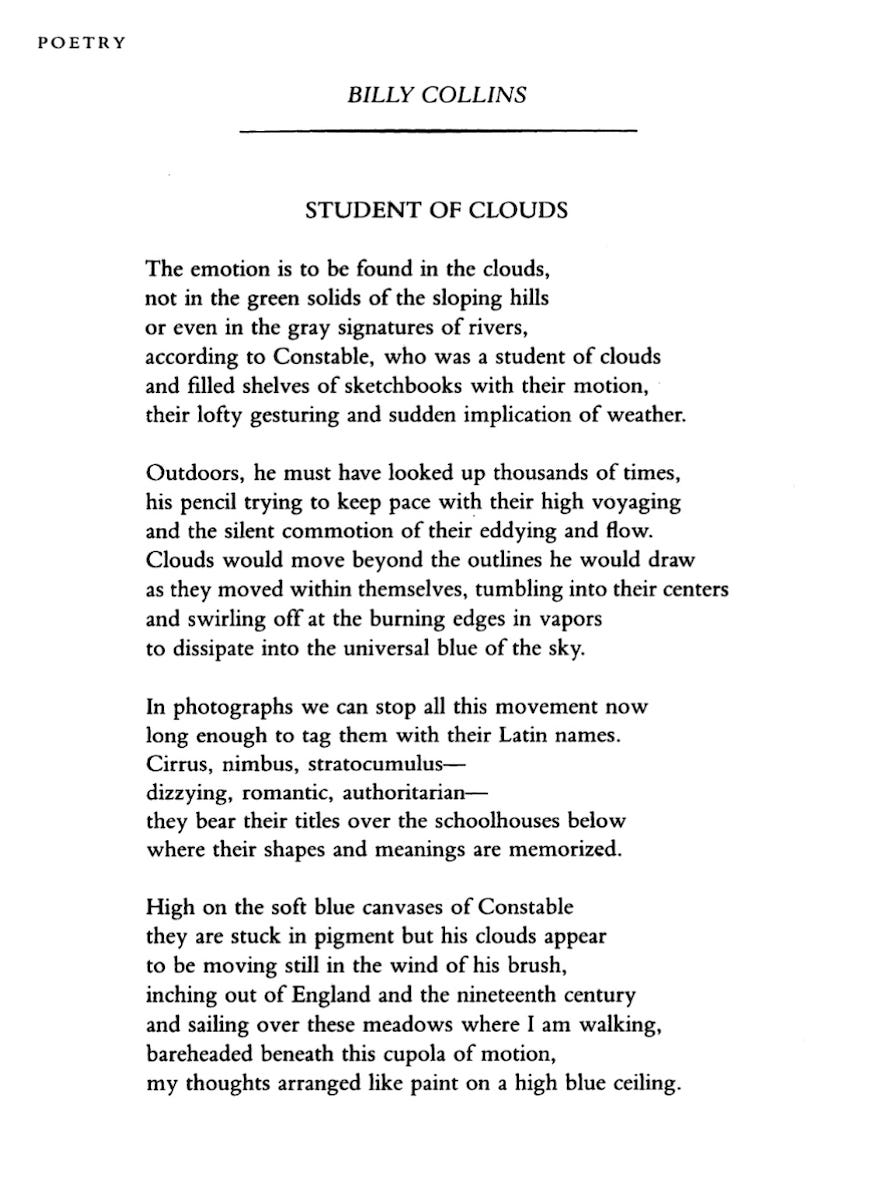

In a favorite of mine, Billy Collins calls him a “student of clouds” and imagines the thousands of times he would have had to turn his gaze skywards trying to get down in paint what he saw above, before it all changed again.

Collins sets up a kind of scale in which the grand movement of the clouds, best understood walking bareheaded through meadows, and well captured on Constable’s “soft blue canvases,” is lost in modernity: “in photographs we can stop all this movement.” It’s all about the movement.

There are so many things that may make Constable’s work with the clouds compelling to poets. There’s the art itself—in which the clouds really do say something. A poem about a piece of art is an ekphrastic poem, but beyond the visual inspiration, there is something about Constable’s work that captures the imagination.2 It’s the clouds themselves, symbolically rich, containing beauty and terror, relief and torment, life and death. The transitory, ephemeral quality that they have, which of course, reminds us of our own impermanence. What poet can resist impermanence?

But still, there’s something more about Constable. There’s the sheer romance of his dedication. To think of him attempting the impossible—capturing the clouds!—with such scientific diligence is quite moving. All the more so because he truly did seem able to reproduce, if not the clouds themselves, then certainly the essence of them with his brush.

Ah, to be painted one hundred times. To be painted one hundred times so well. What poet can resist romance like that?

Sonia’s Poem of the Week, which you should subscribe to.

One of my favorite ekphrastic poems is W.H. Auden’s “Musée de Beaux Arts”, written in 1938 on Brueghel’s painting, Landscape with the Fall of Icarus. Funnily, William Carlos Willams, 20 years later, treated the same subject in a poem of his own, bearing the same name as the painting.