Shorties, pt. 5

Women & Men Edition

After reading White Nights last month, my appetite was primed for a favorite delicacy. The delectable, the bite sized, the itty bitty. The long-short story that’s published free standing, the novela, the poetry collection. THE SHORT BOOK. Whatever the content inside, the skinnier the spine, the more attracted I am. A favorite activity of mine is going to the bookstore—any bookstore will do—and perusing the shelves haphazardly without system, looking for spines that telegraph I am 100 pages or less or if I’m not, I’m only very slightly over 100 pages.1

The blurb on the back usually promises a delightful and or peculiar experience. Herein lies unrecognized or underrated genius, the one true forgotten work, quietly influential material, the inspiration behind the cult following, etc. It’s The Shortie™ (<3), and it is uniquely suited to deliver on all of these promises because it requires minimal buy-in from the reader. I am willing to read just about anything if it’s under (or just barely over) 100 pages. I spend two hours doing stupider stuff than reading a book literally constantly. The writer can do whatever they damn well please, and I’ll read it. We all benefit.

Without, further ado, adding to my running list(s) (here, here, here, here PLUS here, technically), please take under advisement, the following three recommendations.

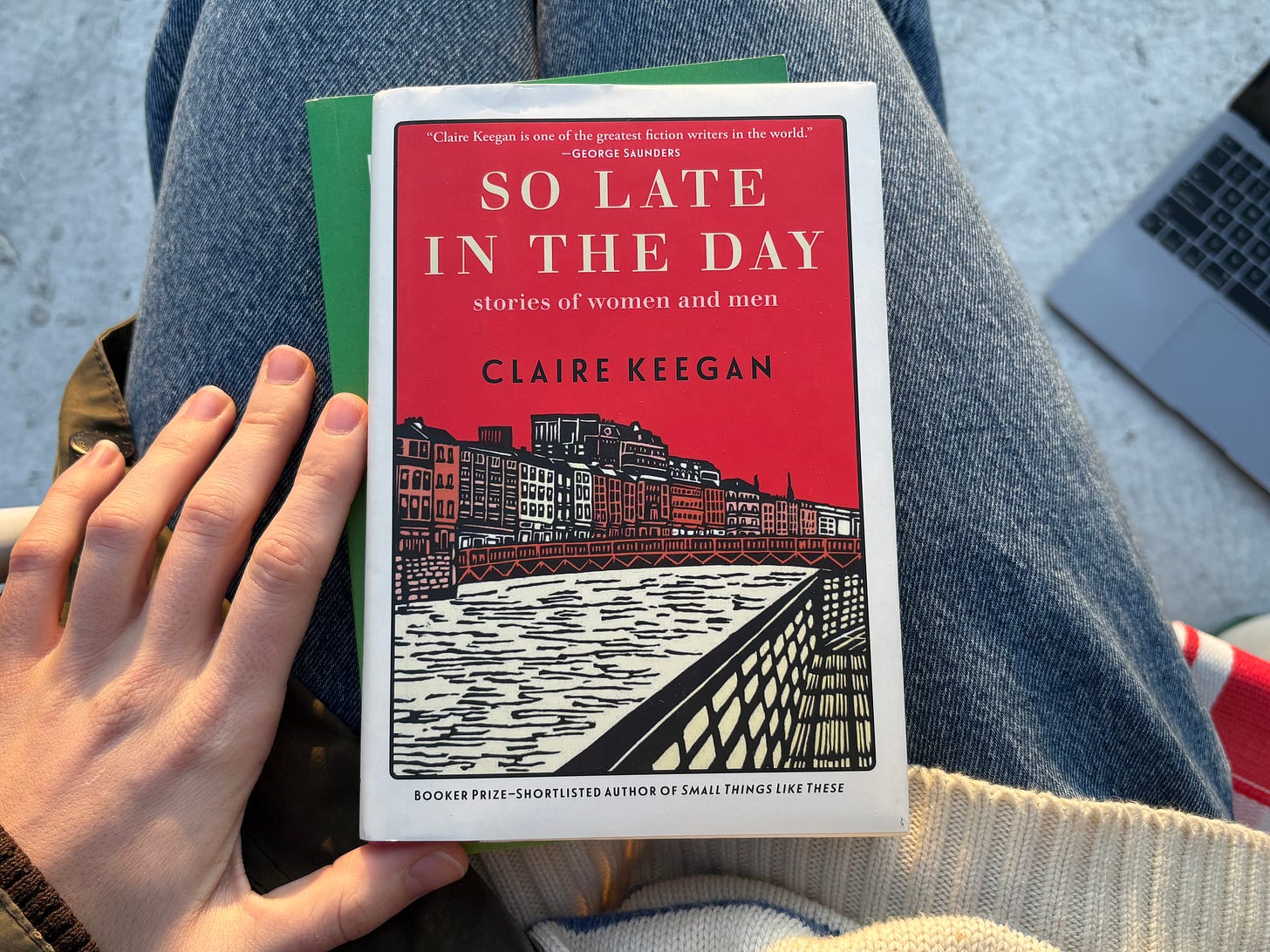

So Late in the Day: Stories of Women and Men by Claire Keegan

Everyone has been telling me to read Small Things Like These, so because I’m a contrarian lunatic, I decided to leave that one on my shelf and read So Late in the Day instead. Like many before me, I must assert that Claire Keegan simply does not miss. I’ve only read Foster and this one so far, but one must imagine that the rest of her work (yes, yes, including Small Things Like These) is equally thought provoking and complete in itself.

It is a great skill to create work that really makes your reader think without also leaving anything to be desired, but Keegan does it. So Late in the Day is a collection of three short stories that, as promised, explores the connections, but mostly the misconnections between women and men.

In the titular first story, Cathal finishes his work day as a civil servant—which involves a budget distribution document and visual arts grant rejection letters—and heads home to a lonely evening. Sabine, the woman he loved and was set to marry will not be at home when he gets there. The dissolution of their relationship—all the petty thoughts and rising resentments that preceded it—is painfully revealed over the course of the story.

In the second story, a writer arrives at an idyllic writing retreat only to be interrupted by a German academic, sticking his nose in where it doesn’t belong. This academic exudes a menacing presence, though the danger he presents is psychological. When the tension comes to a head with an argument on the front garden path after cake and tea, I found myself almost laughing with relief. And then, almost satisfyingly, the writer becomes the menace herself.

The third story2 will stay with me for some time. As the holiday season approaches, a married woman and mother to young children boards a train to the city to go shopping for presents. What she is actually going to do is find a man to sleep with—just to find out what it’s like before she misses her window. She’s getting old and really does love her husband and children. When a suitable candidate approaches at the bar, a ‘romance’ begins that might not end.

In all of these stories, Keegan explores the bridging mechanisms that are necessary in relationships between men and women. These mechanisms span various imbalances in power and gaps in understanding. In her stories, they are broken, crumbling with varying degrees of resultant carnage, but that’s not to say they can never work properly.

Keegan is a master at subtly building tension. Her stories are grounded in a pervading calm until they aren’t. Danger, aggression and cruelty rear their heads suddenly, seemingly without warning, until you remember that a few pages earlier, and a few pages before that too, there actually were warnings.

I often struggle to stay engaged with short story collections, but this one has made me realize that I’m not the problem. Just kidding, it’s made me realize that having less stories and more thematic cohesion is what I want and need. And DESERVE!

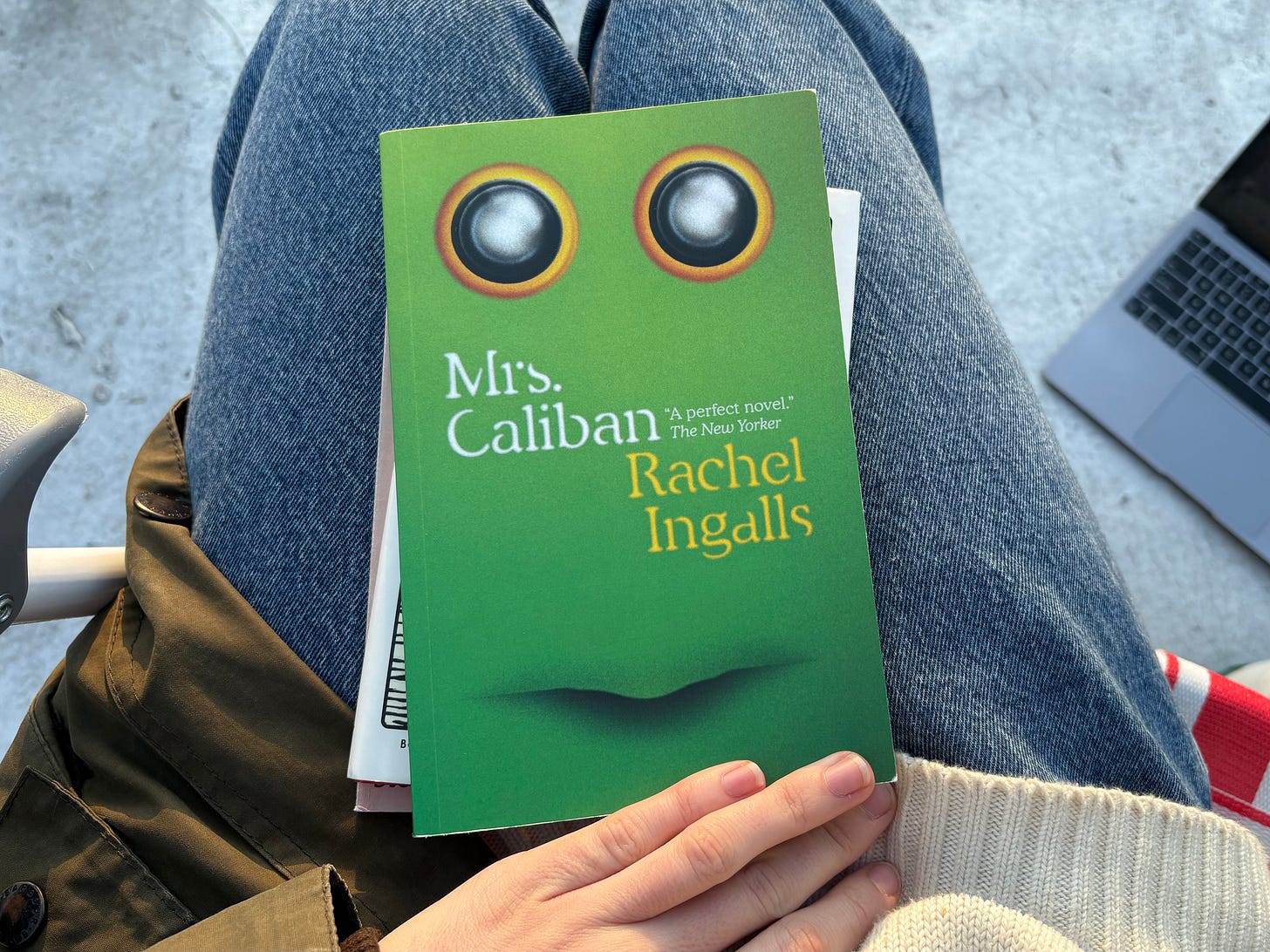

Mrs. Caliban by Rachel Ingalls

I’ve heard so much about this novel, that upon seeing it out on the staff picks table at favorite haunt, Three Lives, I just couldn’t resist. I was there buying a present for someone else, and you know I always say, when you buy someone else a book as a present, you should always get yourself a book too.3 I tend to love anything New Directions puts out.

Mrs. Caliban is the story of Dorothy and her unhappy mid-century marriage. Her husband is Fred, and he’s always running off to “get something signed” or to “pick up a report.” More likely, Dorothy figures, is the possibility that he’s going off to meet some other woman. It’s okay. There is no affection between them. Also no hatred—mostly just nothing.

The way that this unhappy marriage is different from all the rest is that Dorothy and Fred’s young son died unexpectedly under ordinary anesthetic for an appendectomy. This was not too long ago, and so, also in the not too distant past, is the near mental break that the grief brought forth for Dorothy. At the open of the novel, traces of this, shall we say, mental instability remain—primarily in the form of strange personal messages on the radio—normal broadcasts interrupted with personalized assurances like “it will all be okay Dorothy.”

One day, while preparing dinner, she hears a warning about a “monster,” escaped from a research center nearby. He is eight feet tall, has webbed feet and hands and is green. A frog man. And apparently he is dangerous. Not long after hearing about him on the radio, he shows up in Dorothy’s kitchen announcing that his name is Larry. Dorothy takes him in, hides him in her son’s old room (where Fred never goes), and embarks on a tender and affirming affair with him.

There is MUCH to unpack in Mrs. Caliban, but at the core, it is an exploration of the way we treat things that we don’t understand. On the most obvious level, there’s Larry. He is non-human but humanoid. He was tortured in the name of research, and upon growing tired of that torture, brutally murdered the scientists who were enacting it. The reader is empathetic towards him—he is not a monster. But Ingalls doesn’t make him an angel either. Like nature, he can be curious and sweet, or he can be thoughtless and brutal. There is no value assigned to either mode, both modes just are. Society prefers categorization, but Ingalls denies it.

Similarly, Dorothy’s grief over the loss of her son is unmanageable. Difficult to comprehend and inconvenient. The reader is made to understand that the way society—her husband, her doctors, the people in her life—tried to fix this unwieldy grief, was deeply traumatic for Dorothy. She is intensely mistrustful of medications and of hospitals in general, so she doesn’t tell anyone about the things she’s hearing on the radio. She is hiding in plain sight. The reader begins to notice parallels between Dorothy and Larry’s situations and then the reader begins to wonder…

This is a strange little book that defies expectation at every turn. I truly can’t even describe how shocking the end of this novel was. It’s mythical. It’s Shakespearian. Everything that could go wrong goes wrong, and everything that never even crossed your mind as having anything to do with anything else goes wrong too. There’s death (abundant), revenge, betrayal (a truly appalling twist), abandonment—all of it coming fast from all quarters.

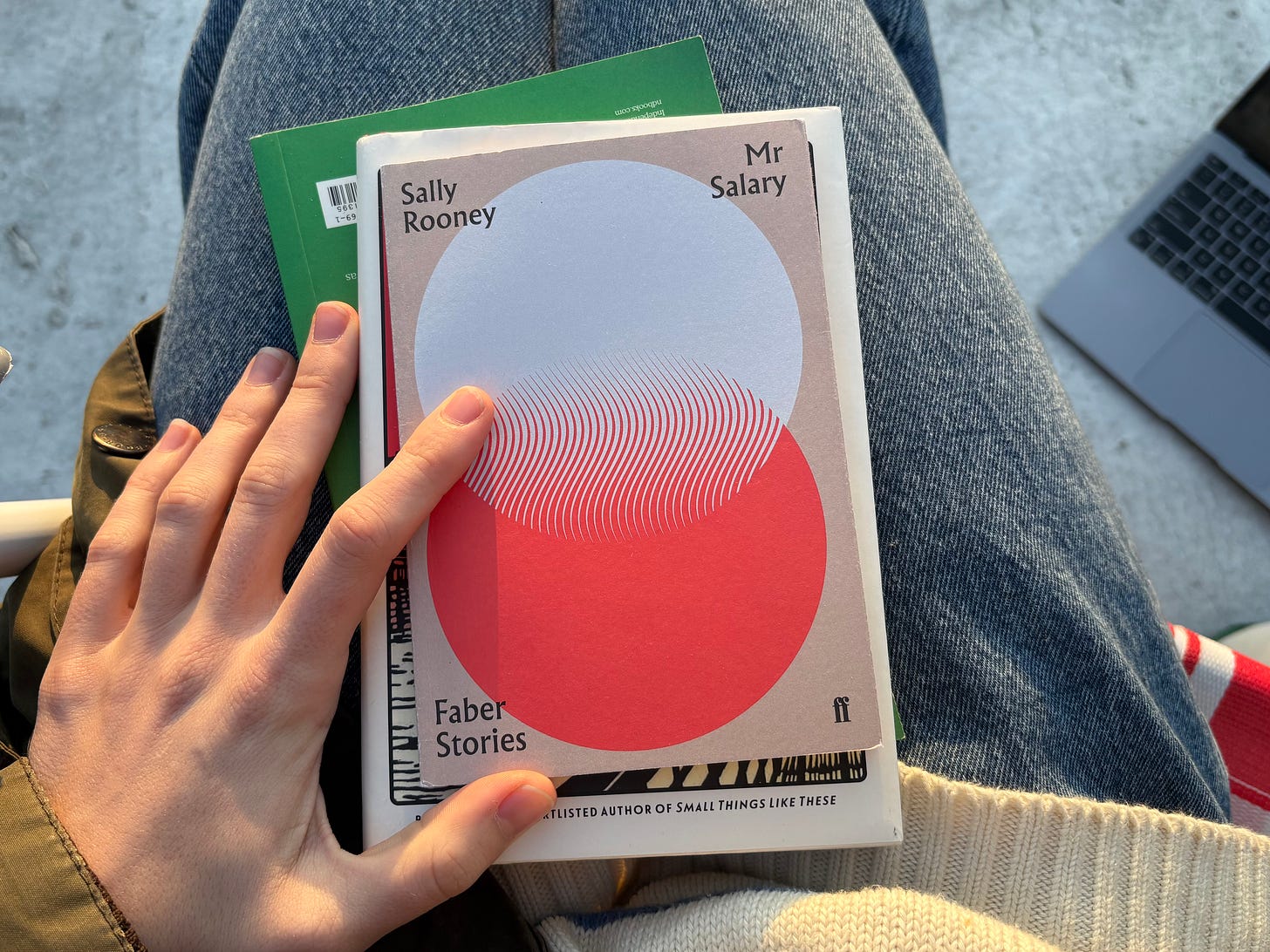

Mr. Salary by Sally Rooney

Much like White Nights, the littlest of the littles is actually a short story that Faber Stories printed in a standalone edition. To cut immediately to the chase, my struggle with Rooney continues unabated. No different than with her other work, I can appreciate her mastery of the language and the immediacy of her writing. Also much like my other experiences with Rooney, I can’t quite make myself like it all the way.

Mr. Salary tells the story of Sukie, who’s mother is dead and who’s father, Frank has a prescription drug problem. Frank also now has lymphocytic leukaemia, which thanks to her desire to “master the distress through intellectual dominance,” Sukie knows will kill him. But that’s now.

The interesting bit comes about five years before the cancer, before the now, when Sukie was nineteen. It was then, seeking a stable place to live while she finished her exams, that she moved in with her uncle’s wife’s younger brother, thirty-four year old Nathan.

The pair quickly develop a strong bond and end up living together for three years. Nathan takes care of Sukie completely, but most notably, financially. Anything she asks for, she will have. Sukie is deeply in love with Nathan. Nathan’s friends don’t quite understand, but he doesn’t care. Sukie, lacking in the way of close friends, and operating as a premature orphan, only has Frank to ignore when he ridicules Nathan.

The themes that Rooney frequently deals in are all present here. It’s a vignette that explores dependency and imbalance in love, with particular attention to age and money. The thing that I found most interesting about Mr. Salary, which actually proved at least somewhat clarifying in terms of my issue with Rooney at large, is the fact that she is addicted to forcing discomfort.

Mr. Salary is a romantic comedy, except for the fact that Nathan is fifteen years older than Sukie, is related to her (if only through marriage and distantly), and has served as a sort of father figure to her. This makes the sexual tension that builds through the story feel…icky. Sorry I hate that word, but really couldn’t come up with better. Rooney introduces these kinds of elements that make her reader (or at least this reader) feel strange about rooting for the love story, but why?

I can get behind it when I can convince myself that her ultimate goal is to argue that romantic love is a redeeming salvation. But sometimes it feels like she’s making her characters a little sick—trying to make her reader uneasy—just for the hell of it. In a short story, with less time to get to know the characters and to grow fond of them, this unease was more intense.

Find out if you agree with me or think I’m prude/lame/puritan/whatever else here.

What is your favorite book at or around or under the 100 page mark!? Please let me know but you’re literally NOT allowed to say Small Things Like These. For obvious reasons.

I literally did this a mere three days ago at Rizzoli and there were so many good skinny spines, I was in hog heaven.

This story is also the titular story in Keegan’s collection Antarctica, which I have not yet read.

Readers with good memories might be thinking, wait a second, I thought the rule was that everyone you buy a present for should also get a book. If you’re also buying a book for yourself every time you buy a book as a present which is every time you buy a present…that’s a lot of books. And those readers would be correct. In summation: I will use anything as an excuse to buy more books, both for others and for myself.

All fabulous writers. Short and sweet is the way to go sometimes.

Oo I like the sound of Mrs Caliban! After last month, I have a new fav shortie which is Brandy Sour by Constantina Soteriou - think it comes in at 105 maybe? But so much punch packed in there - so unique, compelling and fascinating, 10/10 recommend