Last Month's Read

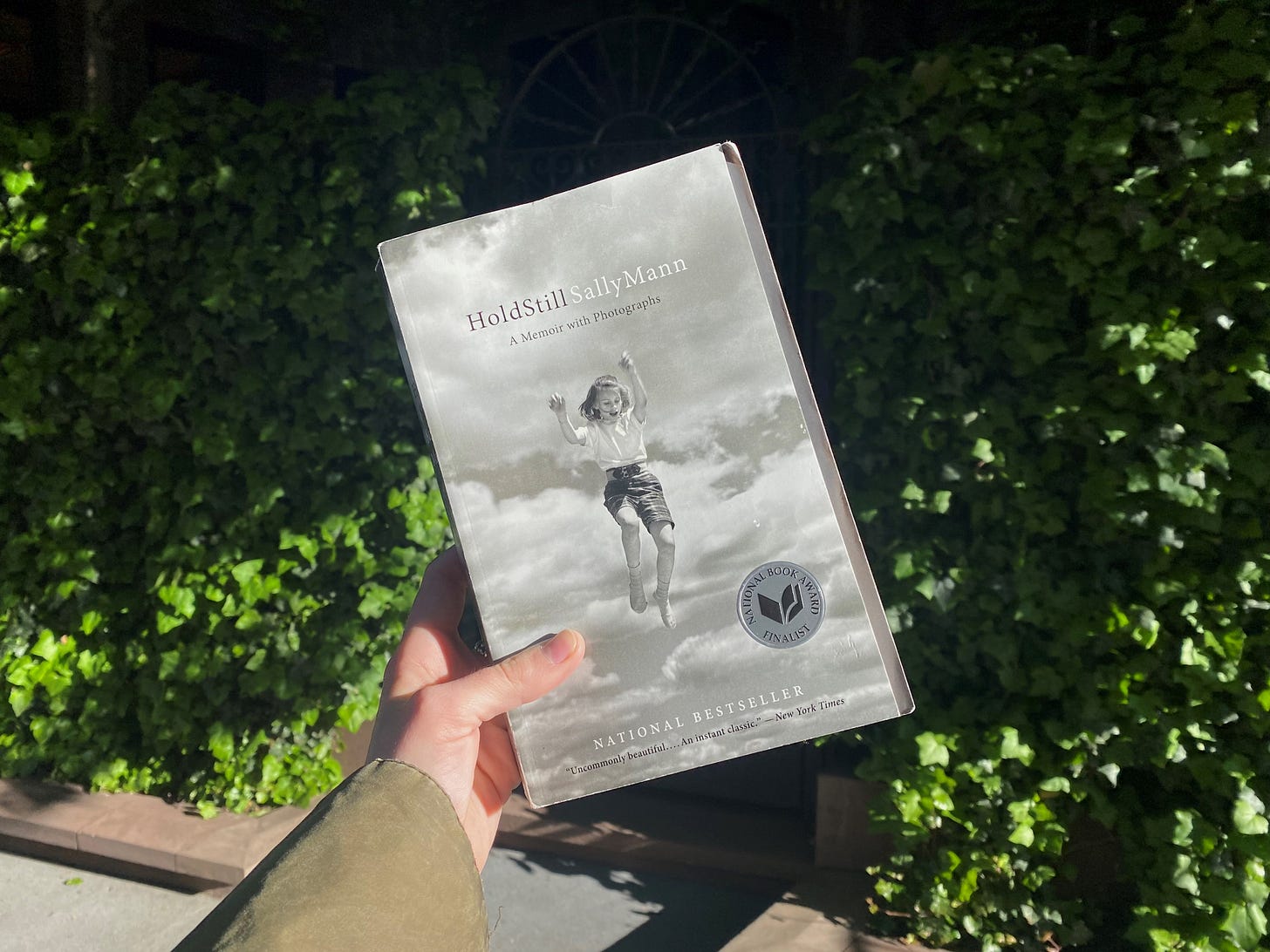

Hold Still by Sally Mann

I am slowly but surely making my way through the books that were given to me by my loving relatives on my 24th birthday. It’s a large stack, and I’m savoring! I’d like to say that I’ll finish them all by my next birthday, but I probably won’t. I just can’t handle constraints or pre-determinate reading order when it comes to my books. I would grow resentful, even though every single one of these birthday books has been absolutely magnificent.1 To any loyal book bestowers reading this, hoping that their book will be next, I’m sorry, but it’s not your turn, and I don’t know when it will be. Unless you’re Isabelle, in which case it is your turn. Isabelle, thank you for this book! It was a delightful read with endless depth.

The book in question is Hold Still by Sally Mann—the memoir she wrote when she was asked to deliver the Massey Lectures at Harvard back in 2011. In determining what on earth she had to say, she decided to plunge into the boxes in her attic. That’s not a metaphor for mining the depths of her psyche - she had literal boxes in her attic, full of her family’s history (and her husband’s and some miscellaneous history of other people too). This book is the long-form result of her reckoning with these “ancestral boxes.” Broken into four sections, it is an exploration of what it means to be from somewhere, geographically, genetically and emotionally—and of what it means to create art from that place.

The first section focuses on Mann’s home in Rockbridge County, Virginia - one of the most beautiful places in the country, and possibly also the world. She talks of her deep, abiding love for the land, and how it has informed her identity and her art (if the two can be separated). This section contains the mostly chronological story of her life, including her utterly delightful romance with husband, Larry, and their life together with their three, controversially photographed children. Those family photographs are the body of work she discusses at length in this section, but more on that later.

The second section is about her mother’s family, and her maternal grandfather in particular - the “sentimental Welshman.” She examines the concept of “hiraeth”—a word of Welsh origin—meaning “distance pain,” or the pain of loving a place. Mann identifies a similarity of spirit in the Welsh people and the American Southerner. Though the land is geographically different, she believes her power for loving it is a direct inheritance. In this context she discusses her southern landscape photography, “emotional pictures…given sincere expression—no trace of irony or ambiguity” (169).

The third section is about her relationship with Gee-Gee, the black woman who raised her, and who was “with the family” for more than fifty years. By Mann’s own account, Gee-Gee was the sole source of outwardly expressed love and affection in her childhood. This section is also about race in the American South more broadly. It ends with Mann’s account of how she has tried to reckon with her many unanswered questions about the personal and collective “Matter of Race,” through portraits of black men.

The fourth section is the longest and focuses on Mann’s paternal family history. It is an interesting tale in its own right, like all of the family stories recounted in the preceding pages (and like all family stories in general, I suppose). It ties the book together quite nicely, with connections to the soul of the southern land, things inherited through generations, and race too. But really, it’s just a vehicle for Mann to examine her relationship with her father, and his relationship, passed on to her through him, with the concept of death. She discusses with aching humanity her studies of death—photographs of Civil War battlefields and somewhat disturbingly, the Body Farm at the University of Tennessee.

Those little summaries feel woefully insufficient to capture the breadth of ideas that Mann covers in her book. I’ve done the best I can to give a concise glimpse. Across it all is a striking study of personal history—an argument for treating yourself like a historical figure in tracing your lineage AND for treating yourself like a character in a book, drawing emotional and spiritual connections from the ghosts of your past to your present. At the core, Hold Still is about how the act of doing this is important for anyone, and essential for the artist.

Just as my summaries feel insufficient, I realize that there is no way for me to cover each of the little and big ideas that struck me as I read along. Practically every other sentence made me think, but there are two things that I’m still thinking about now, a week after finishing this book. First, and perhaps predictably, since mine is not the only mind to snag on it, is the question of the naked children. In the 80’s and 90’s, Sally Mann photographed her children. The photographs of them going about their lives, frolicking and playing and frequently naked, caused quite a stir when they were published in her book Immediate Family.

I have seen at least some of the images included in this book, both online and at a Sally Mann show that I went to years ago at the VFMA in Richmond. I do not find them offensive or problematic in the way that others did (and probably still do). I do not think they’re pornographic, or incestuous, or exploitative. I think they’re art, and I think they successfully and inherently convey the message that the magical quality that ripples out of them is tied inseparably to the land on which they were shot—Sally and Larry’s farm in Rockbridge County.

Mann deep dives into the process of making the photographs and the ways in which her children were involved in that process. Her open consideration of the various claims leveled against her in the years after the photos were released to the pubic make abundantly clear that she was thoughtful in creating this art and that there was no wrongdoing. In addition to pointing out that people were pulling a high-school English class and imbuing every inch of every picture with meaning that simply wasn’t there, the tied-to-the-land, context matters argument was Mann’s simple defense (if defense is even the right word).

The reason I’ve been thinking about the sliver of Hold Still where Mann discusses these photographs—perhaps disproportionately considering how much other good stuff is in this memoir—is because the controversy that boiled up as a result of them is in conversation with a more modern-day problem. Prepare for a bit of a tangent. I recently stumbled across this woman on Instagram named Sarah Adams (@mom.uncharted on Instagram and TikTok). She has made it her mission to expose child exploitation across social media platforms and raise awareness about the dangers that come with posting pictures of young children publicly.

I’m not referring to the average mom posting pictures online so that friends and family can keep up. These people have tens of thousands of followers, if not hundreds of thousands. And the demographic breakdown of followers of many “mommy influencer” accounts is stomach churning. Hint: lots of old men. Adams also highlights cases where publicly posted images are downloaded and used to create deepfake content. The possibilities—though I hate to use a word that has even a note of optimism in it—are increasingly horrifying with widespread access to AI technologies.

It feels wrong to even associate this issue with Mann’s art. To discuss her photographs in the same space as lurking social media pedophiles automatically sexualizes them, and they are not sexual. Besides, I will reiterate that her photographs are art. These social media influencers are not creating art. I think we can all agree on that without me writing a dissertation about ~what art is~. In the most positive light, they’re supporting their families and trying to connect with people, sharing their experience so that others don’t feel alone. I can give the benefit of the doubt – a lot of them might not realize the dark implications that come along with putting their children out there in the world.

Mann didn’t have the same set of implications to consider when she published her photographs—not even close. Her audience was comparatively small, and the technology that exists now to disseminate, alter and manipulate visual “content” simply did not exist then. She received roughly 60 letters total (half positive, half negative, some “what the fuck?”) in response to the publicity her photographs garnered. That number seems so small in a world where leaving a comment or sending a direct message now takes mere seconds.

So, it makes me wonder. If Sally Mann were working on Immediate Family now, would she be more hesitant to do what she did? In some ways I hope not—because her photographs are wonderful and it would be a shame if they didn’t exist. But at the same time, I also do kind of hope she would have paused. When you think about the sick shit that some people do, and the ways that modern technology allows them to do it, it’s impossible not to want to protect children (yours or someone else’s) from being at risk. Take away the fact that Mann’s subjects were her own children, and that introduces additional layers of complexity. Is it the artist’s job to consider morality when creating their art?

If so, is art getting harder to make? I’m not trying to be melodramatic. There will always be art, but it does feel like modernity is creating an ever-growing list of moral landmines that one must avoid, or at the very least, tread extremely lightly upon. Should artists be able to stomp around no matter what, not worrying about landmines? Do they need to be able to stomp around to create their art – art that brings so much beauty and value into the world?

Mann would argue that stomping should be fine, as long as the art produced by stomping is good. Fair enough, though defining “good art” is even harder than defining art. Plus, in so much art, photography perhaps most of all, the artist and the subject walk together. If the artist wants to stomp on a landmine because it’s part of their process, should the subject also get blown up? Mann does address these questions in the context of her own photography, but I’m still left thinking about it—particularly as it relates to our society’s current appetite for “canceling” public figures and yes, artists.

The second morsel that has really stuck with me since I finished this book is also tied to the struggles of modern life. It’s the champagne problem of carrying around a tiny little computer in your pocket that makes life so easy but also makes life less…life-y. This extends to the tiny camera that’s attached to the tiny computer. Mann repeatedly calls out the ways in which photography can permanently alter and ultimately erase our memories. Perhaps erase isn’t totally accurate, but it’s undeniable that photographic memories sometimes replace real memories.

It’s a classic catch-22. We think that we are saving our memories, hoarding pictures so that we don’t forget a moment of this vacation or dinner or concert (one of the most disturbing manifestations of this phenomenon must certainly be the amateur concert documentarian). In reality, we are hindering our ability to remember the experience as it actually happened. It’s a bit disheartening, but it’s also charmingly human. We are just desperate to remember the good stuff. I don’t know if it’s perfect, but when I really want to remember something, I take a picture of it, and also spend some time staring at it really hard. I ruminate briefly on this exact approach (and reference Mann’s beliefs on the topic) in a poem I wrote while I was reading Hold Still. You can find it here if you missed it.

Speaking of memory, now that I’ve spilled all these thoughts out on my metaphorical paper, I realize I’ve forgotten to mention the most important piece of the puzzle. Sally Mann, photographer, is also a gifted writer. I haven’t given it enough attention since I got so carried away ruminating on my modern problems, but Mann is so good, I’m forced to acknowledge that God really does give with both hands sometimes. Her writing is artistic but accessible. She’s conspiratorial, funny, vulnerable, honest. She does NOT equivocate or try to occupy some middle ground of I-see-both-sidedness. She is herself, and she’s a pleasure to spend time with.

Oh my gosh, and as a final thought (more keep coming to me), I also loved the way she talked about her journals. About how stomach churning it can be to go back and read more youthful pages - an effect that I imagine only gets more intense with age - but also how charming. She plans to burn hers (or ask someone else to) before she meets her end, which is very Jane Austen. In my opinion, at least from the excerpts she includes in Hold Still, her writing even from earlier years was quite beautiful, but I won’t stop her from striking the match. Mainly, as someone who keeps a journal, she inspired me not to be so literal in my daily(ish) writing. The biographical stuff will be helpful of course—for the biographers—but I need to give them more to work with than a literal recounting of my daily(ish) activities. There should be more poetic imagery in any place I can put it! Including here, maybe, so watch out.

Oh, also—promise this is the last thing — if it wasn’t obvious, you should absolutely read this book!